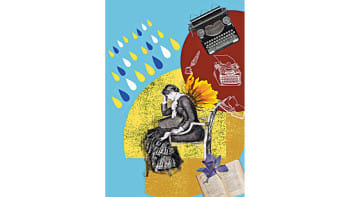

‘Shubeik Lubeik’, wishes, and the vulnerability of human beings

In Deena Mohamed's Shubeik Lubeik (originally published in 2015 and translated in 2023 by Mohamed herself), wishes have not only drastically altered the fabric of daily life in Egypt, but the world at large. Set in 21st century Egypt, the inequalities within Egypt and those beyond are clearly visible in Shubeik Lubeik. From characters suffering because of their socioeconomic position and religion to Western nations exerting their outsized influence on Egypt through trade and treaties, the fictional world is almost a complete replica of the real one. The only change is that wishes exist.

Each genie allows one wish, and they can be divided into first, second, and third class wishes, their positions indicating their strength and quality. Wishes are life-altering; they have invaded entertainment industries, international relations, and even the personal and the sacred, such as struggles with mental health and religious beliefs.

Almost akin to money and oil, wishes are extracted, sold, and weaponised in much the same way that the aforementioned resources are in Deena Mohamed's world. However, genies are sentient, and using a wish requires the consent of the original owner of the bottle for its quality to be maintained. Moreover, making a wish itself is tricky. For instance, resurrection cannot happen but going back in time can. While some wishes, such as asking to look like a celebrity, can be simple with a first class wish, others such as wishing for the intangible, such as not feeling sadness, has unintended negative consequences.

The author also makes clear that the politics of who can and cannot buy wishes is based on real world politics of inequality and distribution. One of the more overt references is the author's decision to call third-class wishes Delesseps, after the French developer of the Suez Canal. These wishes do not work properly, and may even cause grievous harm such as chopping off an arm when a wisher wants to be 10kgs lighter.

The story is set in three parts. Each of the three parts focus on Aziza, Nour, and Shokry respectively. Each of the characters displays a window, not only into the way that wishes have changed how one lives, but the moral dilemmas that arise with having possibilities that never existed before in their world. Each is connected to the other via wishes—both Aziza and Nour for instance, buy their first-class wishes from Shokry, an honest owner of a kiosk, who refuses to use them for himself due to his religious beliefs.

Aziza represents the downtrodden. Her marriage to Abdo, one of the few bright spots in her life, disappears when he is killed by a Mercedes, the very thing he wasted multiple third-class wishes on. Arrested despite having acquired a first class wish with her hard-earned money, Aziza's story highlights the way corruption operates in nations where the poor have little respite from the cruel machinations of those with more authority. When ultimately released through the help of a Dr Nadia from the Wishes for All Foundation, Aziza asks for forgiveness.

Nour, the second customer to buy the wish from Shokry's kiosk, belongs to the affluent section of society. Living in a neighbourhood not visible to those who don't have access to it because of a wish, their struggles with mental health are seen even by some of their classmates as not being logical. One conversation with a classmate involves being reminded that they have neither health nor financial worries, which means that they, in reality, do not have much to be sad about. This is a kind of conversation that many are still painfully familiar with, and Nour's guilt increases after hearing this. A particularly painful moment for them is when they see Aziza has been wrongfully put in jail because of her socioeconomic position, the very thing that protected Nour from the same fate, despite both buying their first class wishes from the same place.

Through Nour's story, we get to see the complexity of wishes compared to other resources. It might be tempting to try to compare wishes to money, labour, or even training that allows for admirable qualities, but in actuality, for many wishes to be fulfilled, a great deal of thought is required. Nour soon realises that they cannot simply wish their depression away. Moreover, considering their privileges, a further struggle is deciding whether they should even use the wish for their own benefit.

Shokry's struggle, in contrast, involves his desire to rid himself of the wishes. Finding them sinful and repugnant to his religious beliefs, he refuses to even allow an advertisement for wishes on his kiosk. His own family history reveals that his father did not make use of the wishes given to him by European tourists visiting the pyramids. He remains staunch about this even when they lose their house, and later we see that Shokry is equally determined to not have a single breach in his integrity.

However, the twist is that Shokry, despite initially seeming so, is not the only main character in the third part. This part switches to another character who has so far remained on the sidelines throughout the novel. Intertwined with Shokry's desire to always help, the character emerges at a time when the continuous ruminations of both Nour and Shokry may feel a bit tedious. This character takes centre stage in such a way that Mohamed's impressive skills as a graphic novelist become evident. It is a welcome reprieve in that it is action-packed, unlike the second part, yet the unpredictable change feels more than fitting.

It is here that we learn of another dimension to wishes, one that separates it from any other kind of resource in terms of what it is able to provide, i.e. the chance to restart life.

This shocking story, which again has the wish as a vital driving force, is stunning, not just because of the fantastical elements, but the deeply tragic narrative that shows a woman enduring what one would never otherwise endure had wishes never existed.

Shubeik Lubeik, like many such works before it, is a clear example of how a fantastical element in a text allows vital truths about the real world to be said. Mohamed makes the graphic novel her own not just in terms of certain stylistic choices, but also through the unique challenges faced by the characters who are moulded by their surroundings—-and of course, wishes. Despite it being set in Egypt, the challenges are ultimately human ones, and allows us the opportunity to ask what we would have done if we had such power in our hands.

Aliza Rahman is a writer based in Dhaka. Reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments