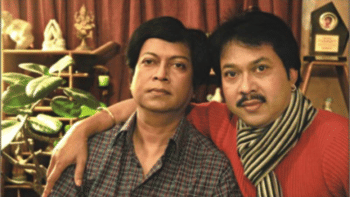

I cry for thee, Sadi

My friend Sadi Mohammad, renowned Tagore singer and founder-director of Rabi Raag, passed away on March 13. My first reaction when my friends passed on the news on social media was disbelief. How could that be? Only earlier that morning, I was thinking of calling him because we had discussed the possibility of my taking music lessons from him over Zoom. Why did he leave so soon? Why now? Why hadn't I called him sooner? All these questions kept creeping up as I was filled with grief.

As I recovered from the shock, I drafted these thoughts and took a broader look at his life and legacy. As a music lover and lifelong devotee of Rabindranath Tagore myself, I realised how much Sadi meant to his admirers and his students. Research shows that the impact of a musician's death is deeply personal yet socially under-recognised. The loss of the parasocial relationship with the musician for me is almost comparable to losing a close social contact.

What a loss! I sat there and tried to take it in. Many magical moments flashed through my mind. I don't remember when Sadi and I first met in person; possibly at a family musical soiree at my cousin Shama's apartment in Gulshan, at Shilpakala Academy when my youngest khalu—Mustafa Zaman Abbasi—was the director general, or much earlier when I was in Dhaka College and he was a student of Class 5, visiting us with his brother Shanu (my classmate). Many other blurred visions crossed before me in a splash of music, tones, and rhythm.

My sense of bereavement deepened as I looked back and remembered our best moments together. Memories of Sadi came bubbling up: his rise through the echelons of musicdom of Rabindra Sangeet on his return from Shantiniketan in the 1980s, of his sweet personal touch which swayed everyone, his deep voice when he performed some of my favourite Tagore songs in person—at my house, on stage, or TV—put me in a state of profound anguish and denial.

My heart soon filled with sadness. I began humming "Tomar kachhe e bor magi, moron hote jeno jaagi" ("May I ask for a divine gift from you, that may I resurrect with the melody of music in the air?"), a devotional song by Tagore that Sadi had once sang for me.

Then, reality set in. I needed to call Shibli, his brother, and my cousin Shama, his friend and student. We met Shibli and Nipa during my last trip to Dhaka at a performance at Shilpakala Academy. Shibli had lately become the flagbearer of the illustrious Salimullah family. Every time I meet Shibli, I can't help but see the images of Sadi in him. The three of them, Sadi, Shibli and Nipa, were like a "band of siblings" and always brought me immense joy when chatting with one or the other. They had come to Boston and stayed with me when my wife organised a fundraiser for the flood victims of Bangladesh in 2004.

Bereavement and coping following the death of a personally significant popular musician is natural. Tagore alluded profusely to these feelings in many of his epic poems, including "Jete nahi dibo," and innumerable songs. Tagore also saw a silver lining around hopelessness: "Achhe dukkho, achhe mrityu, birahodahano laage, tobuo shanti, tobu anondo, tobu anonto jaage" ("Despite misery, death and churning of the estranged heart, There is still peace, still joy, and abundant hopes"). Tagore wrote this after the death of his beloved wife, Mrinalini Devi, at a very young age.

Oh Sadi, I cry for you. I will miss you, and your call in a deep, baritone voice, "Shibli Bhai." I will miss your live renditions of Rabindra Sangeet, which we, your fandom, enjoyed in every nook and corner of this planet, whether in Sydney, New York, or Washington, DC. They say you were mourning your mother's death, who was your lifelong companion. Some even say you took umbrage at society. But we are your friends and we understand your pain. Now, I realise that maybe you were in a profoundly spiritual world, and looking inward. You had lived a full life and you decided, "I am at a crossroads," and interjected, "I am done, it is time for me to go." As Tagore referred to in his song "Ke jaay amritadham jatri," you are the traveller of the holy pilgrim route.

I remember, a few years ago, Bangladeshis living in the Boston area were planning a fundraising event for flood victims in the country. Sadi's name came up immediately. The community of Boston, the artistic hub of the New England region, is greatly attuned to the cultural crosscurrents of the South Asian subcontinent. The Bangladesh Association of New England (BANE) invited Sadi, Shibli, and Nipa. Sadi's calendar was tight, and he was not planning any tour of the Americas. He had his hands full with Rabi Raag, the institution he was building up from scratch. But he agreed to come. Sadi, Shibli, and Nipa came to Boston, and BANE held a grand show with the three in the City of Quincy.

My early memories of Sadi are very sweet. My eldest khala, my mother's younger sister, was the first to mention that I should meet Sadi, the Tagore singer who ascended to fame immediately after his return from India. Shama, her eldest daughter (an architect and a musician), was taking lessons from Sadi and helping him along with Shibli, Amina Ahmed, and Naima Ali build up Rabi Raag, his signature institution. Sadi had charmed khala with his knowledge, dedication, and passion for Tagore. Salma Choudhury, a professor of Bangla literature at Eden College and a Visva-Bharati graduate, was a lifelong follower of Tagore and spent most of her illustrious career researching his life, poetry, and literature. They were kindred spirits and formed a bond. My family welcomed him into our orbit. "What a magical personality," my khala told me. Her motherly instincts kicked in, and she once said, "He is single. A very eligible bachelor. You may want to look for a suitable partner for him."

Wherever you are, Sadi, you will be missed. By your friends, admirers, students, and, above all, those for whom you were a "life coach." You embraced Tagore and inspired us to do the same. Those who come to Tagore do so from various places. We each have our connections and our spirituality. But once in a while, we are all together.

Dear Sadi, friend, brother, guru: it is spring now, and the tune that comes up frequently is "Rodon bhora e boshonto": "Never seen such a spring, soaked with tears. The crimson colour of palash, O my friend blushes my pain of estrangement."

We'll meet again. Soon, or maybe in a few years. And if there is a harmonium or musical instrument in forever land, we'll sing together again.

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and works for Change Healthcare, Inc., an information technology company. He also serves as a senior research fellow at the US-based International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI).

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments