Humanitarian funding: A crisis within a crisis

Every morning, I wake up with a sense of dread as my email is already flooded with requests from different stakeholders—government authorities and humanitarian aid partners — seeking assistance for displaced populations. The stark reality of dwindling global humanitarian funds breeds this dread. If you ask humanitarians how things are going these days, they, too, will tell you they are facing a serious problem: a funding shortfall. There are too many ongoing crises around the world with insufficient funds to help those in need. Regrettably, a quick resolution to this funding crisis remains elusive.

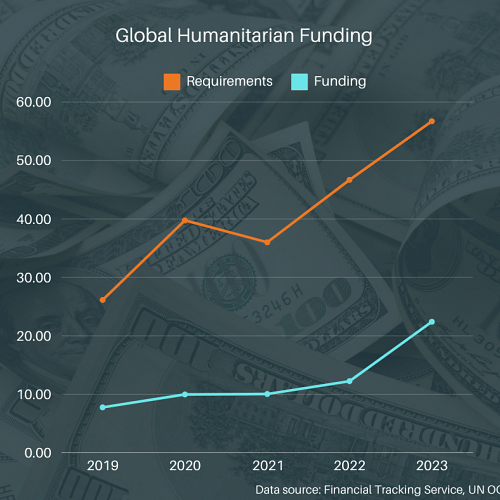

Each year, the United Nations appeals to its member states for funds to respond to global crises and provide lifesaving assistance, including food, sanitation, healthcare, and shelter. In 2023, approximately 128 million people received lifesaving assistance. However, due to funding shortages, humanitarian organisations fell short of reaching their target, assisting less than two-thirds of the people they aimed to support. Response plans for 2024 are ultra-prioritised, with extremely tightened budgets to address the most urgent needs. UN agencies have already been forced to reduce food assistance in Bangladesh, Syria, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Afghanistan, and Yemen. This year, humanitarian efforts aim to reach nearly 184.1 million out of the 302.2 million people who are in need of assistance and protection in 73 countries.

The consequences of these funding shortages are deeply troubling. In Afghanistan, 10 million people lost access to food assistance between May and November last year. This loss worsens food insecurity, raising the risk of malnutrition and hunger-induced issues. In Myanmar, over half a million people endure inadequate living conditions, lacking essentials like shelter, water, and sanitation. Yemen faces a dire situation, with over 80 percent of the targeted people having no access to proper water and sanitation facilities. In Nigeria, only 2 percent of the women in need of essential sexual and reproductive health services and gender-based violence prevention received it in 2023, leaving them vulnerable to severe health risks and increased violence. These examples underscore the urgent need for consistent and sufficient funding to support global humanitarian efforts. Without adequate resources, the ability to deliver life-saving aid and essential services to those in crisis is severely challenged, perpetuating cycles of suffering and worsening existing emergencies. This funding shortfall is causing a crisis within a crisis.

Conflicts, climate emergencies and collapsing economies are wreaking havoc in communities around the world, resulting in catastrophic hunger, massive displacement and disease outbreaks. If the current trends in displacement due to protracted complex conflicts with a high risk of relapse, urbanised conflict, and growing inequality continue, the gap between needs and response will continue to widen.

This underlines the urgent need for more proactive and innovative responses. Business as usual is not a solution now, as relying solely on humanitarian efforts to respond to emergencies falls short in the long term. Therefore, it is crucial that we harness and redesign the way we do business. To initiate this transformation, we must set forth an ambitious agenda and timeline for a total change. The starting point is a fundamental shift away from crisis response towards crisis prevention, focusing on reducing vulnerabilities and addressing the root causes of displacement.

We need to move beyond institutional silos to materialise the ambition. Humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding actors should work towards collective outcomes based on comparative advantages. As we work to ensure that humanitarian needs are met in a principled manner, investing in development and peacebuilding initiatives that target these root causes and prevent crisis from escalating is paramount. Development actors should play a pivotal role in this transformation, concentrating on initiatives like improving infrastructure, education, healthcare, and economic recovery in vulnerable regions. By addressing underlying issues such as poverty, inequality, and resource scarcity, the factors that often lead to humanitarian crises can be mitigated. This approach requires strategic planning, coordination, and steadfast commitment from governments, international organisations, and stakeholders.

Furthermore, prioritising conflict resolution is essential. The international community must pledge to intensify efforts to pursue political solutions to conflicts. Countries must work with greater determination to prevent conflicts and reduce vulnerability. The 302.2 million people affected by crises and destitution must be at the centre of our collective decision-making on humanitarian actions, development, peace and security.

To effectively reduce vulnerability at its core, donors should shift away from funding isolated short-term projects aimed at quick fixes like a band-aid, and instead prioritise funding initiatives that deliver collective, long-term outcomes. Localisation is key in this approach, as emphasised in the Grand Bargain, an agreement on humanitarian reform that was agreed on in the World Humanitarian Summit 2016, that 48 countries and aid agencies are party to. It is essential that we collaborate closely with local actors, ensuring that our efforts empower them rather than replace them. This collaborative effort is vital to get ahead of the curve if we measure success in terms of reducing vulnerability and enhancing local capacity.

Moving towards these changes may indeed require stepping out of comfort zones and embracing new approaches. As the funding gap widens, the focus should be on ensuring that humanitarian aid reaches those in need efficiently. This approach maximises the impact of assistance while maintaining accountability to affected populations. Donors should enhance the effectiveness of their support by offering more flexible funding mechanisms that allow implementing partners to respond rapidly to evolving needs on the ground. This may involve committing to multi-year funding and reducing restrictions on fund allocation. Implementing partners should prioritise maximising direct impact on affected populations by minimising financial intermediaries, overhead costs and administrative expenses, optimising resource allocation towards frontline services and assistance.

Tanbir Uddin Arman has been extensively involved in the management and coordination of humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected populations in South Asia, and Central and East Africa. He can be reached at [email protected]

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments