The unforgettables of Eid

The most puffed-cheeked complaint I've heard from my dearest ones is that I have a bad memory. I seem to forget a lot of what's said to me and what I said to someone, at the moments that were supposed to be and were sweet like Persephone's delusional pomegranates of a binding truce. Lest I freight, I deny these allegations from time to time, because I have memories of my childhood well-secured like a treasure in a safe chest in the chaotic void of my heart. The most treasured ones would be my memories of Eid, in my paternal home, where the green still defies the grey of the mighty cities and a fairytale castle still sits on the side of a river.

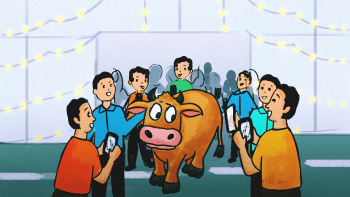

Before I start to draw the drapes of this drama that tries to relive and re-observe the contrast in celebration of Eid from one era to another—I peek out of the glass window between me and the sky and look down. There goes another pickup truck carrying cattle. If I were younger and nearer to the trucks that passed with one or two cows or goats on them, I'd try to see if the buyer "won". Now, though, I look at the hands at the end of the ropes attached to the collars of the to-be-sacrificed animals. The clutch on the rope and the stiffened palms have dirt, scars, and soil on them; the faces hide a gloom, an inexplicable sadness for which words fall short. These animals are like their precious children, on the way to be sacrificed. These fathers sell so much more than just an animal that I wonder whether the worldly sacrifices to match up with the cruelty of reality ever shine brighter on any other occasion.

Eid-ul-Azha was one of the most-awaited, yet fearsome, events of my childhood. The crying sessions of adamancy that started right before the gorur haat day, to include me in the force that was anointed to buy the cow, were on my little girl's triumphs list for days (well, most years). I remember the haats being absolutely laden with cows twice my size and goats, well, my size. I would hide behind my grandfather's shadow and pinch his shirt as we walked through the bamboo bera (fences). There would be mud and many other things that are best left for imagination on the paths that we'd walk in. I visited the same haat after I was no longer a child— and I finally lost the fear of walking, but I had also lost my grandfather's shirt to hold on to anymore.

I caressed the cows for days, tried to be friends, and conspired endlessly about how to convince them to eat from my hands without eating my hand. Then would come the morning of Eid, when I'd be asked to not leave my room till midday. I heard them scream, year after year. I stayed where I was asked to, crying.

There was a ritual of my Dadabhai to offer threads for me to wear so that I don't have nightmares. I believed in his Qaar's, the black threads imbued with his duas, on every Qurbani Eid.

The building of my Dadabari still stands, with our family visiting every Eid, loud and filled with children, sweets and halwa, kheer and puris on constant servings on the tables, fragrancing the whole house and the roads—that is Eid to us.

Everywhere that is not my dadabari, Eid has felt foreign. As if I am visiting from someplace afar, with no Dida to feed me puris after puris. But sadness befalls me when I see kids peeking from the balconies of the tallest buildings in this metro, with their blank eyes. A cartoon-printed Eid card was all we asked as children before the Eid holidays—a charm long lost in the 5.5-inch display of a smartphone.

Sitting still in my dadabari's most light-filled room all day now, I deny the complaints of my ill memory once again, because when I close my eyes, I still see myself sitting on a brick wall in a chilly, foggy winter morning wearing a monochrome glittery sweater with uncountable little kids, watching the Eid jamat in front of me, listening to the muezzin's declarations aloud, and waiting for my dadabhai, father, and others to come running for me. Those fast-paced, smiling walks of my family are my signature on time's immortal wings.

Tahseen Nower Prachi is a writer.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments