Iran’s presidential elections: A smokescreen?

During Iran's latest presidential elections, the hashtag #electioncircus was trending among the Iranian community on X. This may be due to the illusion of a political competition that is encouraged by the Velāyat-e faqīh, or Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, in an established theocratic system, where presidential elections are mostly a facade because ultimately, the decision-making power rests with the Supreme Leader.

So, how do presidential elections work in Iran? The Shourā-ye Negahbān (Guardian Council) handpicks the most suitable candidates from a pool of presidential candidates, who then compete against one another. To secure victory, a candidate needs more than 50 percent of the people's vote. If no candidate achieves this majority, a run-off ensues a week later between the two candidates who received the highest number of votes in the initial round.

And what is the Guardian Council? It constitutes 12 members who are directly/indirectly appointed by the Supreme Leader, who hold power to vet/veto legislation, and oversee elections. The Guardian Council can bar candidates from standing in elections to parliament, the presidency and the Majles-e Xobregân-e Rahbari (Assembly of Experts). For example, Ali Larijani, an ex-parliamentary speaker and former Commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, was disqualified during the 2021 presidential elections by the Guardian Council, possibly owing to his center-right ideology. Noteworthy to mention, disqualified candidates are disallowed from protesting the council's rejection.

Among the seven candidates who were selected by the Guardian Council for the 2021 presidential elections was the to-be president, Ebrahim Raisi, a far-right hardliner, known as the "Butcher of Tehran" for his role in allegedly carrying out mass executions of up to as many as 30,000 political prisoners in 1988, as the-then Deputy Prosecutor General of Tehran. Following Raisi's death after a helicopter crash on May 19, 2024, new presidential elections took place shortly after, which culminated on July 5, 2024.

This time, out of 80 candidates, 74 were disqualified by the Guardian Council, which included four female candidates, as has been the case for all presidential elections since the Islamic revolution—a testament to the accusation that Iran is a gender apartheid state. According to Iran's Ministry of Interior, there was a record-low turnout since the inception of the Islamic Republic, where only 40 percent of the more than 61 million eligible Iranians voted during the first round, which evidences that most do not support clerical rule. I will skip any comment on the speculation that even these embarrassing numbers are fabricated, as has been the claim, given the staggering majority's decision to abstain from voting.

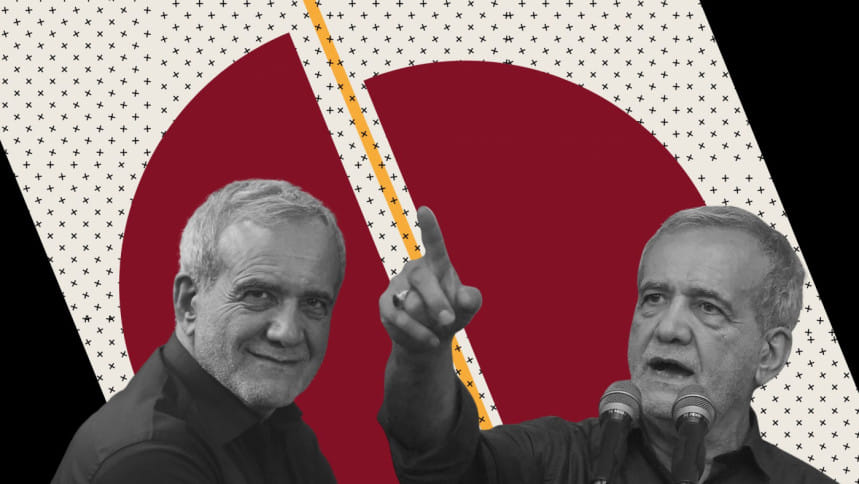

Among the six selected candidates this time around, Dr Masoud Pezeshkian was the only so-called "reformist"—a widely circulated theory that has thrown dust in the eyes of many non-Iranians. It won't be too absurd to assume that Pezeshkian's approved candidacy by the Khamenei-controlled Guardian Council was a ploy to increase political participation. Pezeshkian won against ultra-conservative Saeed Jalili, but one wonders what moderate reforms he will he bring about without challenging the state's theocratic system, especially when he himself has given a public statement declaring that confronting Iran's power elite of clerics will never be part of his agenda.

Anyone who understands Farsi can easily find Pezeshkian's stance on women's rights. In an interview, an elderly Pezeshkian proudly states that even before the first Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, established the mandatory hijab law in 1979, Pezeshkian enforced women to wear long trousers, the long-sleeved manteau (a long overcoat), and the hijab at the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (where he was pursuing an MBBS) as well as at the hospital across the medical college. One alumna of the university recounts incidents from 1979, when Pezeshkian and his comrades, whom she dubs as "terrorists," attacked and harassed women who didn't comply, and even carried weapons, such as knives and chains, as scare tactics.

Should a reasonable skeptic, who relies on the independent investigation of the truth, believe that the same man who didn't believe in women's right to freedom of choice is now a changed "reformist" under the same regime that has committed human rights violations in relation to the Zan, Zendegi, Azadi (Woman, Life, Freedom) movement in Iran? Should I, a Bangladeshi citizen belonging to the Iranian diaspora, believe that Pezeshkian will, for instance, make any legislative amendments to dismantle gender apartheid? Or will he be able to ensure a stop to persecutions against non-Shiite religious minorities such as the Baha'is, who are barred from having tertiary education and government jobs, whose properties are confiscated, whose dead are denied the right to dignified burials?

Even if Pezeshkian is given the benefit of the doubt, what power does he hold at the end of the day? None, really. It is therefore disappointing to see every international news portal misleadingly labeling the new president as "reformist" or "moderate" or to see clickbait titles such as the BBC's "Iran's new president gives hope to some women and younger voters," when the content of the article itself goes on to say: "…with Ayatollah Khamenei having final say over government policy - there is little chance of real change," and "…regardless of Dr Pezeshkian's win, the supreme leader remains the 'puppeteer' in Iran."

Noora Shamsi Bahar is senior lecturer at the Department of English and Modern Languages, North South University (NSU), and a published researcher and translator.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments