The cheapening of life and the struggle for the state

We have reached a point of no return. Only two questions matter: How did we get here, and what do we do so that we never get here again? The quota reform movement and its aftermath have served as a prism, casting light on the tremendous inequalities that have been produced in Bangladesh over the past decade. From the beginning, this regime staked its existence on the power of accumulation and patronage—opening Bangladesh up for business to all in exchange for loyalty. In the process, this once proud party became a violent, extractive club that anyone could join by saying the right words. State, government, and party have become one, through a process that Gramsci called "passive revolution": an elite, state-led effort to catalyse economic development while absorbing competition and neutralising enemies (that is why this is different from fascism).

That is what "being like Singapore" really means. This development has been real, despite what many like to claim. Bangladesh has transformed beyond recognition, a transformation concretised in the new national monuments (like the Padma Bridge). Enormous fortunes have been made, making this once "basket case" the home of countless millionaires. Certainly, some of that wealth has "trickled down." But our exports bring in billions because we can squeeze down wages by any means. We have rented out vast swathes of the land as EZs and EPZs, where the "normal" rules don't apply. Scandal after scandal have revealed the fortunes made using connections, or by directly using the state apparatus, funneling their wealth to tax havens, businesses in Dubai, or homes in Canada. We boast of remittance income, while the people who make and send that money—often in terrible conditions—receive nothing but neglect. These are not accidents; accumulation needs disposability. Wealth grows at the cost of someone else's life.

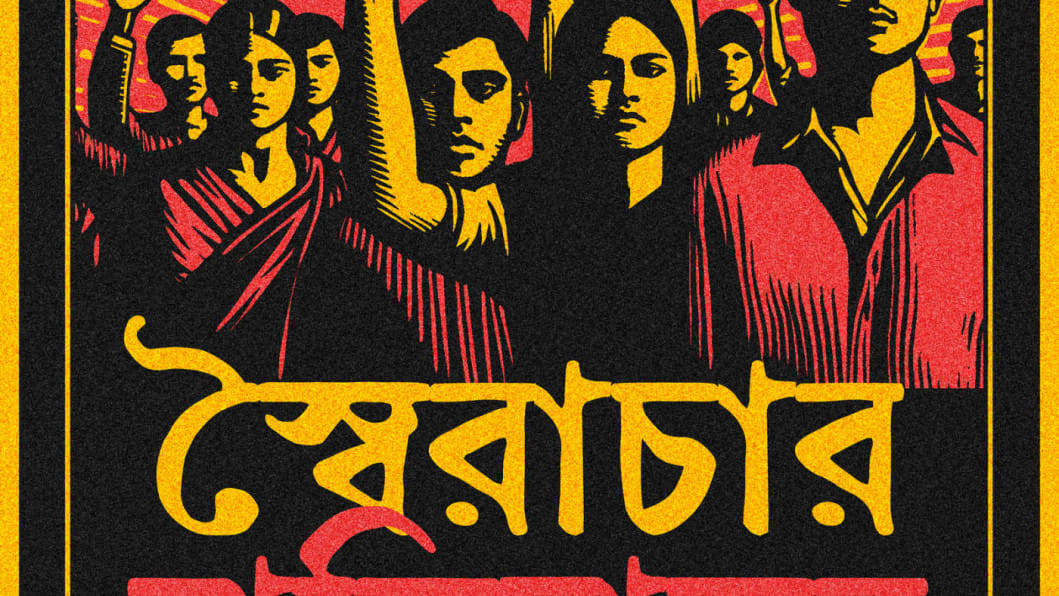

Those who could find patrons, who could "buy in" their fealty, could claim a share of the pie, which is precisely what the 30 percent freedom fighter quota came to represent: a loyalty card. The quota reform movement was reborn when the frustrations of primarily middle-class students—facing jobless growth and a lifetime of precarity—combined with increasing resentment at blatant corruption, state violence, and clear disdain for the public. The official reaction to the carnage on July 19—the obsession with vandalism and indifference to the human cost of repression—only reinforced the sense that this was a government for itself. After that point, nobody was really interested in talk about "third parties," real or otherwise. Why was it that the first to join the students on the streets were those who will neither pay tax nor ride on expressways? Why did Dhaka's rickshaw-pullers bring out solidarity processions? Just as these students recognised their dispensability—which is what turned government jobs into lifelines worth fighting for—they found natural allies in those the nation leaves behind, who have no other means of laying claims on the state. As the crackdown unfolded, however, many of us who do pay taxes and ride the metro remembered that we are punished with higher tax rates than money launderers, that our wallets are worth less and less while some build resorts, and that our students, our children, are being killed. Strange bedfellows have been brought together out of this sense of disposability. This regime has made some lives far too valuable, while making others so cheap that they have nothing more to lose.

This regime believed that as long as they could keep the money flowing and enroll enough investors into their gamble, they could ignore the land and river-grabbing, the broken roads, the waterlogging, the unemployment, the inflation, the energy crisis, the money-laundering and corruption, and the brewing resentment; the last could be dispelled by the might of the ever-ready foot soldiers and police, seemingly given a limitless "right to violence." Perhaps they truly believed that they had a permanent, historical mandate to rule. But the true fragility of this project has now been laid bare. This movement has many troubling dimensions, and we have written about some of them. But what it has done is provide a conduit, through which students and others have learned to transform their frustrations into structural questions to put to the state, questions that it has failed to answer with a consistency that almost begs belief. The scale of death and destruction—and the license to kill—defies anything that our predecessors faced in the 50s and 60s, or during the anti-Ershad movement. They have crossed the "red line," making any more talk of negotiations suspect.

There is much to learn from these repeated comparisons to the past. In the 1960s, a group of Bengali economists put forth the famous "two economies" thesis, an articulation of internal colonialism based on extractive development: channeling the resources of the East to furnish the development of the West, leaving some scraps for the "peripheral" elite and keeping the rest in line by force. The struggle for Bangladesh was born when those scraps were no longer enough, when middle-class frustrations aligned with the dispossessed. But what happens when the "two economies" are not separated by geography and language? When we cannot distinguish "the enemy" from ourselves?

We have been trapped in this cycle of "peacetime war" ever since the end of the war itself, toppling regime after regime with little to show for it. Our state has remained a colonial apparatus, designed for extraction and middleman-rule. Since the transition to democracy, each regime has busied itself with enrichment, patronage, and (mutual) annihilation. The institutions we built have either fallen to partisanship or have had to insulate themselves for survival. The absence of any civil society interventions in the quota reform debate while there was still time is no less a failure than the state's. For years, we academics have made no real attempt to address the misalignment between graduation and employment rates. The media's role in engineering the "rajakar" fiasco should not be forgotten either, nor the unwillingness of so many university administrations to protect their students. We all have much to answer for.

It really did not have to come to this. Elite club politics, the counsel of sycophants, and the passion for vengeance have squandered all of the potential the last 15 years had held. The 2008 elections had carried many hopes: a thriving economy and a mature political system amongst them. If only we had learned to respect human life and make the state-civil society-people triad function. Instead of fulfilling her father's dreams, Sheikh Hasina has repeated his mistakes, and has walked straight into the same trap. And while this is a new horizon in many ways (especially for this generation), we have also been here too many times before. No hero, technocrat, or general will deliver us, nor will the death of party politics. Either we finally build a people's republic—which requires a lot more than elections—or we condemn ourselves to repeat this "legacy of blood" until there is nothing left to fight over.

Seuty Sabur and Shehzad M Arifeen teach anthropology at the Department of Economics and Social Sciences, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, BRAC University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments