The invisible prisoners of state

My father Shafiqul Islam Kajol's lifestyle of publicly criticising and calling out any ill activities of the then Awami-ruled government would often prompt my mother to make comments such as, "You're going to get disappeared any day now." These comments were, of course, made as light jokes. Yet, when on March 10, 2020, my father didn't return, it took us more than a day to realise what had happened. When people turned away from us, when the unwelcoming feeling at the police station became apparent, when the voices on the calls became soft, that's when we realised that my father had been forcibly disappeared. Even then, there wasn't a definite moment when we knew for sure. No one breaks the news to you clearly.

Among the hundreds of different illegal activities that go on around the world, some have the unique characteristic of not being identifiable as a crime. Enforced disappearance is one such activity. Often these incidents cannot be validated officially as crimes while the related government is in power as the state's resources are used to carry out this crime. These state-sponsored crimes are justified by claiming they are carried out for the sake of the government or to protect stakeholders in the government.

The countries and states where enforced disappearance is possible have one common characteristic: these are states where you cannot vocally express or talk about the atrocities of the powerful. Often, the powerful derive their power solely from the state itself, serving as a quid pro quo. The state gets immunity from any criticism, and the persons running the state get full access to the state's resources at their fingertips; they can unleash it without any backlash or accountability. Soon, the state resources become available for them to use for their personal gain.

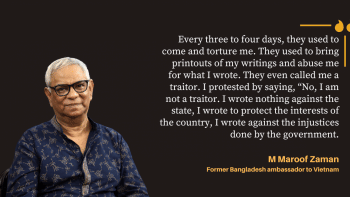

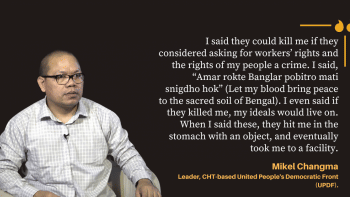

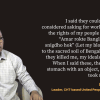

The enforced disappearances under the last government had two distinct categories. The first type was perhaps the easiest for them to authorise. These were politically influential people whom the government feared so much that the all-too-common scenario of politicians always being legally persecuted, arrested, and put in jail was not enough. For whatever the reason may be, the party in power didn't even want them to have any legal shield. This group also included individuals from important sectors and even former high-ranking officials of government bodies.

The second type of enforced disappearance was carried out against people who were personally deemed troublesome for individuals in the ruling government. Perhaps they had sensitive information about the individual or had other animosity. Since these individuals in the government were extremely influential, they could easily pull strings to make their targets disappear without much hassle.

The media's gag played a massive role in enabling this heinous crime by the state. The most the media would do is report on the missing aspect of these disappearances. They never mentioned the state's involvement in the disappearances. The media would only show statements from some politicians blaming the disappeared and spreading false information about them, such as how the missing person was perhaps a loan defaulter, a criminal hiding from cases, or involved in some other scandal. Law enforcement officials would state that they had no idea about the missing person's whereabouts. And then everyone would move on.

The media never received any official message about the restrictions on reporting cases of enforced disappearances. But the multiple cases under the Digital Security Act and other laws that a news outlet faced after publishing news severely critical of the government was a sufficient warning message for everyone. My father also served as such a message when the government decided to show my father as "found" on May 3, 2020, World Press Freedom Day. His arms were tied behind his back, and he was dragged to court like a petty criminal and sent to jail. The timing of my father's reappearance on World Press Freedom Day was not a coincidence.

The horrors of a family member being disappeared are not easy to put into words. Of the people who disappeared, a mere fraction came back alive. Some were found dead, far away from the place where they were last seen. The worst thing about these ordeals is that the family waiting for the person never gets closure. They don't get a deadline. They don't get a message. They are forever left hoping, even after weeks, months, years, sometimes decades, that maybe one day their loved one will come back.

The hopes of the family members were sparked on August 5 at the fall of Sheikh Hasina's regime. A select few even went back to their families around that time. But the majority are still missing. Yesterday, under Dr Yunus's interim government, Bangladesh became a signatory to the United Nations treaty on enforced disappearances. Earlier this week, the interim government set up a commission to investigate incidents of enforced disappearances that occurred during Sheikh Hasina's 15-year tenure.

While the formation of the commission and the signing of the UN treaty on enforced disappearances is applaudable, the list of victims of enforced disappearance must be formally finalised as soon as possible. The list should also be inclusive of all those who have disappeared. Any political bias should not play for or against the entry of a name to that list. Upon finalising the list, anyone still missing, must immediately be released, if they are still in one of the many secret detention centres called the Aynaghar.

The victims of enforced disappearances must also be protected. While the Awami League government is not in power now, the law enforcement agents who have actively participated in these disappearances still operate within these agencies. Even Awami League's own goons are not to be ignored. They are violently dangerous by themselves. The security of the victims who are returning or have returned must be ensured.

The current government must also identify those who have been killed during their disappearances. While that is the last thing these families want, this closure is a must. When and how these victims were picked up, and under whose order—all of this should be made public. Every person involved in these disappearances must be brought to justice immediately. Furthermore, some sort of compensation must also be considered, as it was the state's duty to protect these people, yet it was the state's resources that ended up ruining their lives, taking away their legal and human rights. We all know how justice delayed is justice denied. We are already delayed by 15 years. The interim government must ensure that the wait doesn't extend to the hands of the next government.

Monorom Polok is a member of the Editorial team at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments