Bangladesh’s criminal investigation system needs reformation

In 1849 French writer Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr wrote: "The more things change, the more they stay the same." This may be briefly interpreted to mean that despite drastic societal changes, certain fundamental aspects are so deeply rooted that they remain unchanged overtime, unless consciously and decisively addressed.

The criminal investigation for a serious offence in Bangladesh generally begins with a written complaint—General Diary (GD) or First Information Report (FIR)—lodged at a police station usually by a victim or a relative, but sometimes by someone without any locus standi, accusing any number of named or unnamed individuals. There is no requirement for a declaration of the truth by the complaint or an objective assessment of the veracity of the complaint.

This complaint forms the basis on which those individuals may be arrested and remanded in police custody for up to 15 days and then in prison until trial, unless bail is granted at some stage. They spend months or years incarcerated while still innocent in the eye of the law. It may be months before the strength of the case is assessed by the court. The principle, formulated in the 19th century by the British rulers, is that arrest and incarceration first and investigation later. No regard for human liberty, no respect for the truth—it served the purpose of keeping a subject race down by instilling the fear of mass arrest and incarceration at will. Inheriting this legacy through the Pakistani rulers, the successive governments in Bangladesh found it expedient to keep the colonial concept intact.

The impact of the injustice of the inherited system is less apparent when a government in power is relatively tolerant of the rule of law. But an authoritarian regime, such as the one which has just been overthrown, takes full advantage of the system—resulting in numerous false cases against innocent people, torture in police custody and imprisonment for months without charge. It is no wonder that Bangladesh's ranking in the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index has gradually fallen to 127 out of 142 countries—sandwiched between Zimbabwe and Mozambique—in the last 15 years. The score is even worse when the criminal justice system is singled out within the rule of law context.

In "the 36 days of July 2024," Bangladesh was shaken to the core. The seismic transformation swept away an authoritarian and murderous regime. The sacrifice by the students and the efforts of people living at home and abroad was enormous. The goal was clear—henceforth, in an utter break away with the past, meritocracy shall prevail, and democratic values, including the rule of law, zero tolerance of corruption, freedom of speech and human rights shall be the driving force.

Naturally, the 15 years of impunity, with which offences such as extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances, extortion, money laundering and gross misuse of public office were committed by those associated with the former regime, came to an abrupt end. In particular, it was expected that those truly responsible for killing hundreds of students and maiming thousands would be rounded up within days of the fall of the dictator to face justice. What was not expected was that the same arbitrary method of arrest and investigation process, befitting only of the regime as brutal as the one overthrown, would be followed.

On August 21, 2024, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued a circular directing the police not to refuse GDs, FIRs or complaints and to process them speedily. Cases are now being filed on a daily basis in all parts of the country. It is not unusual for a murder allegation to name over 400 individuals as suspects. Each one of them becomes liable to be arrested and remanded in police custody without any further investigation. There have been incidents of arrests and remand of individuals, who may have been suspected of financial crimes or other misdemeanours, but there is not a shred of evidence connecting them with the murder offence in question.

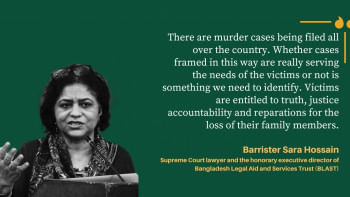

This trend needs to be corrected urgently. This is because it brings the interim government into disrepute. Secondly, while the international community and the rights organisations at home and abroad have not spoken out yet, they are certainly observing the developments closely. Thirdly, the interim government would not be able to persuade any foreign government to return those suspects, who have managed to flee the country, when such arbitrary arrests and incarceration are prevalent in the country. Fourthly, as Barrister Sara Hossain has pointed out, the way these cases are being framed, they will not be able to pass the initial stage. Thus, many are likely to be discharged before the trial stage since no real efforts seem to have been made to collect independent and forensic evidence. Imagine the scenario, where these individuals walk out of prison with the hero's welcome from their followers.

In Bangladesh, wholesale reform of the criminal investigation and justice system is necessary for it to be compatible with the values associated with the rule of law. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss such reform. However, the interim government could consider giving several directives to the police and court as a first step.

These directives can include ordering police to register complaints themselves in relation to as many cases of the killings as possible, conduct the initial investigation as to the person who actually did the act, and then follow the chain of command upwards to where the order had initiated from. Police officers, who have actually committed the act of killing or injuring, must be interviewed as suspects, while bearing in mind that some of them may have acted in self-defence and others may invoke the defence of duress from their superiors.

Besides, only the victim, a relative of the victim or someone in some tangible way affected by the crime should be allowed to lodge a complaint, GD or FIR. The document must have a declaration of truth, with the warning that if it is later found that the complainant has knowingly provided false information, they may be prosecuted for an offence. Also, an arrest should only be made when the officer in charge is satisfied that there is a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed the crime in question. The basis of that suspicion must be recorded. The individual must be told the allegation for which they have been arrested. Moreover, the officer in charge must ensure the prisoner's total safety to and from the court. Where facilities are available, with the consent of the prisoner, interim hearings could take place via video link allowing the prisoner to appear from a suitable room in prison.

Regarding remand in police custody, it should be an exception rather than the rule. The police must strictly justify why they need further time in police custody. The magistrate or the judge must give sufficient reason for allowing police remand. Meanwhile, a suspect must be offered to have a lawyer of their choice, registered with the bar council, present during the police interview and interrogation. The suspect must be informed that they do not have to answer questions, but that in such circumstances, the court would be at liberty to draw adverse inferences from their refusal to answer questions. Where a suspect complains of physical assault in police custody, the magistrate or judge before whom they appear, unless found not to be credible, must order an examination of the person by an independent medical professional and submission of the medical report to the court.

As the interim government took charge, its declared mantra was reform, reform, reform—which resonated well with the people. In that spirit, the above steps would be a good start as the current government embarks on reforming the criminal investigation and justice system.

Najrul Khasru is a British Bangladeshi barrister and a member of the judiciary in England. He worked for 20 years in the Criminal Justice System in the UK, training magistrates and police.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments