The need for truth and reconciliation in Bangladesh

For over 15 years, under Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian regime, the people of Bangladesh endured rampant oppression and untold cruelty. The regime was characterised by state-sponsored torture, enforced disappearances, maiming, and pervasive human rights abuses. Cruelty was employed as a deliberate tactic to suppress dissent and erode people's democratic aspirations. The oppressive system was maintained with impunity by the state machinery and bureaucracy. As a result, the state is widely mistrusted and seen by Bangladeshis as anti-people.

Given the scale of corruption and brutality orchestrated by the regime, the judicial system alone cannot swiftly or adequately deliver justice. The institutional nature of the crimes and urgent demand for accountability call for a truth and reconciliation process (TRP), similar to the one guided by South Africa's post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

A TRP, led by a commission or council-type body, would expose the human rights violations without relying on retribution. It would provide a platform for victims and witnesses to share their stories and give perpetrators the chance to confess their crimes, bringing the atrocities to the fore. This process would help Bangladesh (re)build a just and accountable society, by creating a culture that listens to victims and addresses past atrocities transparently.

By focusing on restorative justice, the TRP could help break the cycle of vengeance and promote a peaceful transition to democracy. This approach is essential for rebuilding a society after prolonged injustice, as it establishes a foundation for accountability, reduces impunity, and restores public trust in institutions. Additionally, by demonstrating that truth-telling and reconciliation can be powerful tools for healing divided societies, the TRP could help form a moral centre for the country, establishing new norms and institutional safeguards to prevent future abuses.

The TRP should be tailored to Bangladesh's unique situation with a focus on: i) investigating human rights violations like killings, torture, and abductions between 2009 and 2024. The TRP would present its findings on the extent of state-sponsored violence to the public; ii) offering victims a space to tell their stories and recommending reparations and rehabilitation to address national trauma and promote healing; and iii) considering amnesty for those who fully disclose their actions based on set criteria, which may be limited to lower-level perpetrators who followed orders or helped cover up abuses.

The concept of addressing state violence and delivering accountability through the process of victim testimony and perpetrator confessions emerged in post-apartheid South Africa. Following the end of apartheid, a brutal system of racial oppression that spanned from 1948 to 1994, the newly elected government of Nelson Mandela sought to confront past injustices without resorting to retribution or further violence.

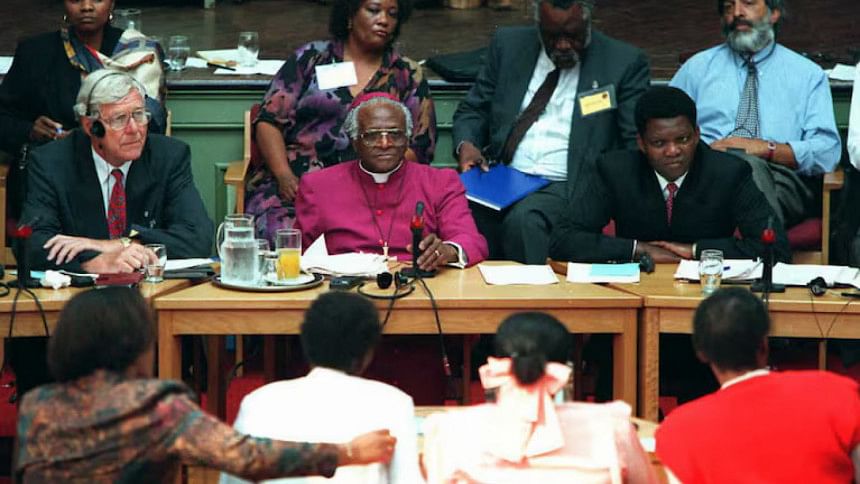

The TRC was created in 1995 through the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, to uncover the truth about the atrocities committed during apartheid. The commission was chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a respected anti-apartheid activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. His leadership was crucial in guiding the commission's work with a moral and ethical focus on reconciliation.

The TRC had three main committees: i) Human Rights Violations Committee: investigated human rights abuses like killings, torture, and abductions committed between 1960 and 1994; ii) Reparation and Rehabilitation Committee: focused on restoring the dignity of victims by recommending reparations and rehabilitation; and iii) Amnesty Committee: assessed and granted amnesty to perpetrators who came forward and fully disclosed their actions.

The TRC held public hearings across South Africa, where victims could tell their stories and perpetrators could confess their crimes. These hearings were often emotional and widely covered in the media, exposing apartheid's horrors to the nation.

The TRC successfully revealed the extent of apartheid-era human rights violations, with thousands of victims coming forward and many perpetrators confessing. By focusing on restorative justice, the TRC helped prevent a cycle of vengeance and facilitated South Africa's peaceful transition to democracy. Its public hearings encouraged national dialogue, essential for forging unity and healing.

However, it faced challenges and criticism. Some believed that amnesty allowed perpetrators to escape justice, and others argued that it did not address systemic injustices or offer sufficient reparations to victims. Moreover, the government did not fully implement the TRC's recommendations for reparations.

Despite these challenges, the TRC remains a landmark effort to address a nation's violent past. By uncovering the truth and promoting reconciliation, it played a key role in South Africa's transition from a divided society to a democracy.

As Bangladesh grapples with the aftermath of Sheikh Hasina's autocratic regime, it must ensure that justice is timely and effective. The nation needs closure and healing from the trauma inflicted by years of state-sponsored violence and oppression.

A well-designed TRP can offer a path to healing. By uncovering the truth, giving victims a voice, and fostering reconciliation, it can help break the cycle of violence and write a new chapter in Bangladesh's story—one that must be different from its past.

We are at an inflection point in shaping the country's future. How we address its dark past will define its social fabric, establish norms, and set the tone for the future. It is crucial that we get this process right.

Tamina Chowdhury is a policy, legislation and advocacy specialist based in the US.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments