IPO approval turned into a recipe for market mischief

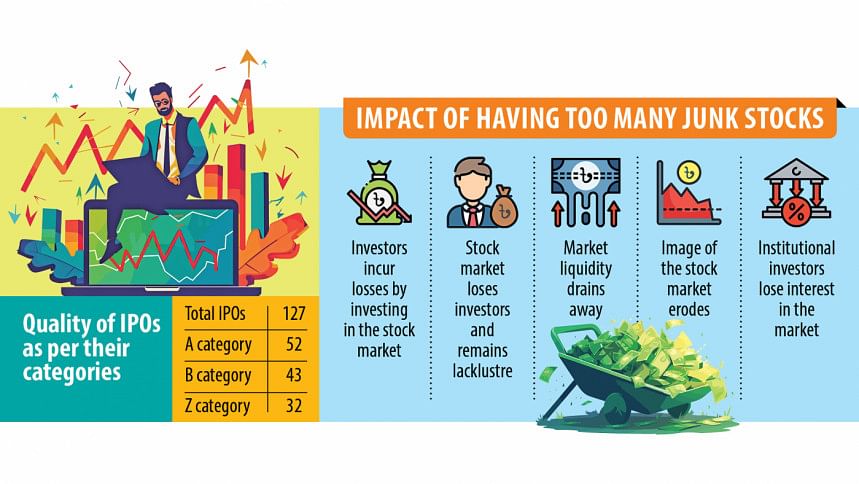

The stock market regulator approved 127 firms for listing in the past 14 years, allowing their transition from private to public companies. However, the subsequent outcomes are disheartening as most of these companies showed declined performance rather than growth.

A significant number of the enlisted firms -- roughly one-fourth of the total companies at the bourses -- became junk after going public.

This left share market experts to conclude that many of the companies listed during the last 14 years through initial public offerings (IPOs) were actually underperforming.

Of the 127 companies approved in the last 14 years, only 52 remained in the 'A' category, while 43 were downgraded to 'B' and 32 to 'Z'.

In other words, 40 percent of companies maintained their A category status after listing while 60 percent experienced a decline in their categories.

A company paying less than 10 percent annual dividends is classified as 'B' while 'A' category companies must pay at least 10 percent.

A company is downgraded to 'Z' if it fails to declare dividends for two consecutive years.

The 'Z' classification also includes failure to hold regular annual general meetings, production suspension for six months or having a negative retained earnings balance exceeding the company's paid-up capital.

Besides, a company is downgraded to 'Z' if it fails to pay at least 80 percent of the announced dividends.

According to official data, 'Z' category shares in 2011 amounted to around 8 percent of the total issuances while it spiralled to over 10 percent in 2024.

Minhaz Mannan Emon, a former director of the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE), said the premier bourse of the country rejected nearly 70 percent of IPO proposals after analysing their financials, but the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission (BSEC) disregarded these recommendations when granting approvals.

According to Emon, while stock exchanges worldwide usually list companies without any major involvement from market regulators, the BSEC deviated from this norm by taking a more active role in the listing process in Bangladesh.

Many of the companies listed during the past 14 years had relatively insignificant performance, he said. To facilitate their IPOs, these companies often provided undue benefits to top officials of several government agencies.

For example, Matiur Rahman, a former top tax official who made headlines for the extravagant purchase of a sacrificial animal and subsequent job loss, obtained placement shares in several companies without paying a single penny, Emon mentioned referencing multiple media reports.

"This must have negatively impacted these companies," he said.

Such activities weaken newly listed companies, he commented. "As a result, the stock market is now filled with 'autistic companies' that are harming the overall market."

According to the former DSE director, even companies that sold shares at a premium saw their performance declining.

A premium is an added amount to the face value of a share when a company is considered well-performing and deserves a higher share price at issuance.

During the discussed period, nearly 51 companies were issued premiums -- some set by the stock regulator and others through bidding among institutional investors.

Of them, shares of 30 companies subsequently fell below their premium price. The most devastating development was five companies -- Appollo Ispat, Ratanpur Steel Re-Rolling Mills Ltd (RSRM), Regent Textiles, Zahintex Industries and GBB Power -- turned junk stocks afterwards.

While adverse economic conditions can sometimes contribute to the declining health of a company, Emon said the fall of many listed companies could directly be attributed to their "underlying intentions".

The BSEC introduced the premium determination system by the regulator. Appollo Ispat even sought a premium of Tk 10 per share, while the regulator unprecedentedly increased it by Tk 2 to Tk 12.

Later, the regulator launched a book-building method, where institutional investors set the premium through bidding.

However, some institutional investors manipulated this system by placing higher bids to benefit themselves. In response, the BSEC introduced a more stringent valuation method to prevent institutional investors from bidding excessively.

Kazi Monirul Islam, CEO of Shanta Asset Management, said the Dutch bidding system, in which an auctioneer starts with a very high price, incrementally lowering the price until someone places a bid, should be reintroduced to attract quality companies to the market.

If a good company does not get fair prices, they will be less encouraged to enter the market, he said, adding, the regulator should punish anyone who bids high prices with bad intention, but the system itself should not be abolished.

Islam said the stock market needs good companies with strong financial health and the current stringent valuation method in book-building is a major obstacle to attracting them.

In the 14 years, only one multinational company, Robi Axiata, and one state-owned company, Bangladesh Submarine Cables PLC, have listed.

Regarding the reluctance of good companies to enter the market, Md Moniruzzaman, managing director of Prime Bank Securities, said non-listed companies have fewer reporting and regulatory obligations and can obtain bank loans more easily.

"So, why would they come to the stock market?" he questioned. "In most cases, those who have financial difficulties and cannot access bank loans are the ones who turn to the capital market."

The National Board of Revenue (NBR), Bangladesh Bank and the BSEC should sit together and formulate a policy mentioning a company will not get bank loans up to a certain amount without getting listed, said Moniruzzaman.

Besides, companies exceeding a specific profit threshold could be mandated to list or incur higher tax rates, he commented.

According to the Prime Bank Securities managing director, the culture of tax evasion also needs to be addressed strongly to encourage non-listed companies to go public. By strengthening efforts against tax evasion, the lower tax rates for listed companies would become more attractive.

While these policies can be effective, investors must also exercise caution and avoid subscribing to IPOs from companies with poor prospects.

In response to a question about the responsibility of merchant bankers in bringing low-performing companies to market, Mazeda Khatun, president of the Bangladesh Merchant Bankers Association, said issue managers prepare documents based on the information provided by the issuer and do not monitor companies after listing.

So, issue managers cannot assess the performance of companies after their IPOs. If accountability can be ensured for all the stakeholders, including the auditor, the situation will improve, she said.

Although Bangladesh has many well-performing local and multinational companies, they are not interested in getting listed. Commenting on this issue, Khatun said most of the companies do not want to come to the market as they think it may hurt their comfortability.

On the other hand, the tax gap between listed and non-listed companies narrowed instead of widening, she added. At present, the corporate tax gap is 5 percentage points while it was 10 percentage points several years ago.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments