Why police transformation is critical for Bangladesh

Bangladesh stands at a crucial crossroads. The political shift following the July-August 2024 uprising, which led to Nobel Peace Prize laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus taking charge of an interim government, signals that the demand for change is no longer avoidable. These protests, originally triggered by job quota grievances, swiftly morphed into a nationwide outcry for justice, accountability, and a call for systemic reform.

The police force's role in the uprising was undeniable. Hundreds of people lost their lives, many due to the heavy-handed tactics of law enforcement, intensifying public outrage and distrust. This isn't new. For years, Bangladesh's police force has been seen as an arm of political repression rather than a protector of the public. This system has long prioritised control over community engagement, fostering an environment of systemic dysfunction and division. Allegations of extrajudicial killings enforced disappearances, and arbitrary arrests have steadily eroded public trust. The police, tasked with serving and protecting, have too often been perceived as upholding a narrow political agenda at the expense of human rights and justice—a hard truth that Bangladesh can no longer afford to overlook.

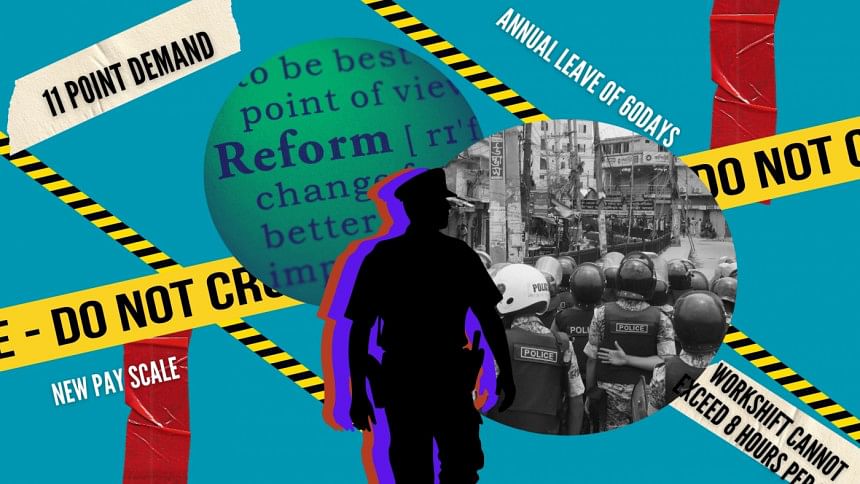

The unrest during the revolution also claimed the lives of police officers, a tragic reminder of the deep rift between law enforcement and the people they are sworn to protect. These fatalities reveal that police officers themselves are often trapped in a cycle of violence and mistrust, operating in a high-pressure environment with insufficient resources, inadequate training, and excessive working hours—factors that have a detrimental impact on the overall effectiveness and morale of the force, as highlighted in the 11-point demand presented by police personnel in August 2024.

Yet, every crisis offers an opportunity. The recent formation of the Police Reform Commission is a vital first step, but this alone isn't enough. The path forward demands lasting, transformative change—change that penetrates deeply into the core of police culture, behavior, structure, and laws. The events of July and August have made it clear that the current state of the police force cannot continue. The question we must ask now is: how do we make this reform meaningful, sustainable, and capable of restoring trust between the police and the people?

At the heart of Bangladesh's police reform lies the urgent need to move away from the outdated colonial-era Police Act of 1861—a law that prioritises control rather than service. In 2007 and again in 2013, the UN supported the drafting of a new Police Ordinance under a police reform project, which ran from 2006 to 2016. This draft ordinance promoted democratic, citizen-centred policing, emphasising public oversight and accountability, including the creation of an independent Police Commission and a formal complaints mechanism for reporting abuse. Yet despite its promise, the draft ordinance and the 2013 review of the act had stalled at the political level.

A new legal framework on policing could provide a strong foundation for transforming Bangladesh's police force into a professional, accountable, and efficient service. This will build sustainable systems that prevent abuses, protect vulnerable citizens, and foster a relationship of trust between the police and the communities they serve.

The goal of police reform in Bangladesh must be to establish a force that is democratic, people-centred, and responsive to the diverse security needs of society. This will require a complete overhaul of the existing system—from legal frameworks to police welfare, institutional strengthening, training, and community engagement practices. The police must be seen as protectors of public safety and human rights. This reform also requires a systemic approach and the Anti-Corruption Reform Commission and the Judicial Reform Commission will also be instrumental to shaping the police force.

Reform should result in a force that serves all people equally, regardless of political affiliation, gender, ethnicity, or social status. Professionalism, integrity, and impartiality must guide every action, ensuring that the police safeguard all citizens, particularly those most vulnerable to abuses.

Human rights must be embedded in the very fabric of police operations. This isn't only about preventing extrajudicial killings or arbitrary detentions; it's about ensuring that every interaction between police and the public is rooted in respect for human dignity and the rule of law.

Lastly, accountability must be a priority. The police must be held to the highest standards of conduct, and abuses should be met with swift and impartial justice. Establishing independent oversight bodies is essential to ensure transparency and genuine accountability.

Bangladesh is not alone in its struggle to reform its police. The UN has supported police reform efforts in many countries, including Nigeria, Pakistan, Iraq, and Kenya—nations with similarly politicised policing and public mistrust. In these countries, public demands, like those currently in Bangladesh, have been vital in calling for independent oversight mechanisms to hold police accountable and ensure that reports of misconduct are investigated without interference.

Reforms have focused on making the police more responsive to the public's needs, particularly regarding issues such as gender-based violence, and protecting the most vulnerable, especially women and children. Community policing has proven to be an essential method for rebuilding trust. By engaging directly with local communities, police forces become more responsive and effective, gaining critical insights into the challenges people face.

While Bangladesh can learn from international experiences, it must tailor its reform to its own context. The Police Reform Programme of 2006-2016 offers valuable lessons. Although it improved training and professionalised certain aspects of the force, it also highlighted the deep-rooted political challenges that hinder sustainable reform. A key takeaway from this experience is that sustained political will and genuine public participation are essential to ensuring lasting change.

Public engagement must be central to the reform process, not an afterthought. In a country like Bangladesh, where youth-led activism has made it clear that the status quo is no longer acceptable, the voices of young people must shape the future of law enforcement. Nationwide dialogues with students, women, marginalised communities, and victims of police misconduct will ensure an inclusive reform process that reflects the aspirations of all Bangladeshis. Trust cannot be rebuilt in isolation—it must be founded on transparent, open communication between the police and the public.

The time for police reform in Bangladesh is now. The interim government, led by Dr Yunus, has made an important first step by establishing the Police Reform Commission. But real reform requires more than political will—it demands active involvement from civil society, the international community, and, above all, the people of Bangladesh.

The UN is committed to supporting this transformative journey. Our experience in other countries demonstrates that meaningful reform is possible—but it requires collective effort, driven by transparency, accountability, and public engagement. This is a unique opportunity for Bangladesh—not just to reform its police force but to reimagine the role of law enforcement in society. Let's seize this moment to create a future where justice, security, and dignity define the relationship between the police and the people they protect.

Gwyn Lewis is the resident coordinator of the United Nations in Bangladesh.

Stefan Liller is the resident representative at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Bangladesh.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments