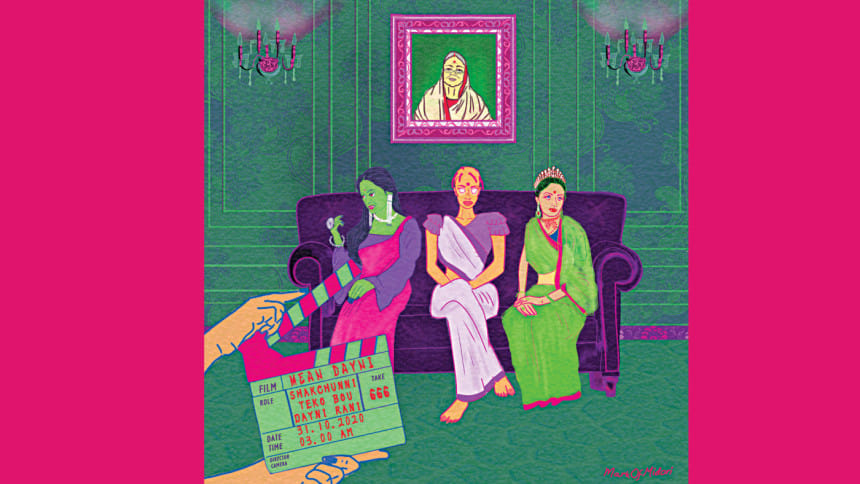

An interview with Shakchunni

Growing up, I always heard of Shakchunni as a horror story. She was the eerie figure hiding in the shadows, a warning whispered by elders to scare children into obedience. A consequence of disobedience, a symbol of danger, of what happens when women "stray" from the path society sets for them. But as I grew older and began to look deeper into her tale, it became clear to me that Shakchunni was more than just a ghost story. Think about it—how often do we hear of the villains and "bhoots" in Bangla folk horror being women? Almost every time, they are wronged by society, by religion, by culture. And Shakchunni stands out as the biggest example. But have you ever wondered what she thinks, or what her side of the story is? Because behind the bangles that jingle ominously in the dark, there is a voice—a voice that has long been silenced.

Today, we sit down with Shakchunni herself to listen to that voice. Not the folkloric version, but rather the woman who was forgotten, cast aside, and misunderstood.

Shakchunni, let's start at the beginning. Can you tell us about your life before you became the Shakchunni we've heard about in folklore? What were your dreams and aspirations?

Under the shade of the ancient Banyan, I once laughed and played. Now, I watch, bound by invisible chains of traditions and expectations, as the world below fears me. I was a devoted wife, subjugated by the patriarchal norms of society.

Could you elaborate on the societal pressures and circumstances that led to your transformation?

I was made to believe that my ultimate goal was to serve my husband and his family. I poured my soul into being the devoted wife that society demanded. And what did it get me? Betrayal, isolation, and a lifetime of thankless sacrifice. When my husband committed the ultimate betrayal of infidelity, it wasn't he who was blamed; it was me. I was labeled as lacking, as if my worth was solely dependent on keeping a man faithful. It was a maddening, cruel joke played out at my expense.

In Thakurmar Jhuli, your story is often associated with fear and malevolence. How do you feel about this portrayal?

Thakurmar Jhuli? The book that's revered as the epitome of Bangla folk tales? Let me tell you, my portrayal there is a farce. It simplifies my narrative into one of villainy, conveniently forgetting the systems that created me. I'm not malevolent; I'm a product of malevolence. I'm not the monster; I am the response to the monstrosity that was my life.

What are some pivotal moments that shaped your identity as Shakchunni?

My life was a tapestry woven together by betrayal, expectations, and societal norms. But if you're looking for milestones on my road to becoming Shakchunni, consider the day I was branded as a failure by my in-laws because I couldn't bear children. Or perhaps when my husband's affairs became the talk of the town while I was advised to "maintain the dignity of the household" by staying silent. Each incident chipped away at my humanity, and what was left was a hollow, anguished shell. I became Shakchunni not by choice, but as a last refuge.

If you were to confront society today and speak your truth, what would you want to say to challenge the perception of women like you in folklore and history?

Confront society? Ah, what a delicious thought! I would say, "Stop making us your cautionary tales and start making us your catalysts for change." Don't relegate us to the pages of Thakurmar Jhuli as lessons of fear; include us in your modern dialogues as the embodiment of rebellion against a rotten system. We're not symbols; we're the stark reality of what can happen when a society stifles its women.

Your story has been passed down through generations, often as a cautionary tale. How do you feel about being used as a warning rather than a person with her own struggles and challenges?

Do you have any idea how infuriating it is to be reduced to nothing but the moral of a story, a whispered warning in the dead of the night? In a just world, it wouldn't be my story scaring young women; it would be the tales of unfaithful husbands and cruel in-laws. But no, in the grand tapestry of Bangali folklore, it is I who must bear the burden of being the cautionary tale. And yet, here we are, sitting under this ancient Banyan tree, and I have been relegated to the role of a boogeyman, a grim tale to be recounted but never understood.

What can we learn from your story? Are there lessons or insights you would like to share with those who may have misunderstood you?

Learn? You want to know what can be learned? How about not reducing a woman's existence to mere lessons for your self-improvement? My story isn't a neat little fable wrapped up in a moral; it's a searing testament to a lifetime of pain, betrayal, and societal dereliction. You want insight? Don't trivialise my suffering or commodify my pain for some profound takeaway. Understand this: there are countless women whose stories are never heard, whose cries are stifled, and whose lives are confined to the margins of your folklore. Listen to them. Believe them. Change for them. Because if you don't, you are not just failing me. You're failing all of womankind, and you'll find that history, despite its feeble whispers, has a tendency to scream back in the end.

Kazi Raidah Afia Nusaiba is a contributor at The Daily Star Books and a student of IUB.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments