2 wars changed Syria’s fortune

In every crisis lies opportunity, and in every opportunity lurks crisis.

The startling advance of Syria's opposition in a week is the unintended consequence of two other conflicts, one near and one far. It leaves several key US allies with a new and largely unknown Islamist-led force, governing swathes of their strategic neighbor – if not most of it, given the pace of events, by the time you read this.

Syria has absorbed so much diplomatic oxygen in the past 20 years, it is fitting this week of sweeping change popped up as if from a vacuum. Since the invasion of Iraq, the US has struggled to find a policy for Syria that could accommodate the vastly different needs of its allies Israel, Jordan, Turkey, and its sometime partners Iraq and Lebanon.

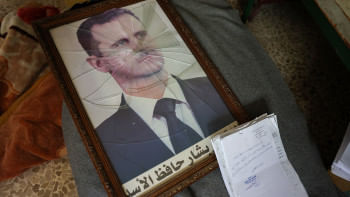

Without the physical crutches of Russia's air force and Iran's Hezbollah, Assad toppled when finally pushed

Syria has always been the wing-nut of the region: linking Iraq's oil to the Mediterranean, the Shia of Iraq and Iran to Lebanon, and Nato's southern underbelly Turkey to Jordan's deserts. George W Bush put it in his Axis of Evil; Obama didn't want to touch it much in case he broke it further; Donald Trump bombed it once, very quickly.

It has been in the grip of a horrifically brutal dictatorship for decades.

The swiftly changing fate of Bashar al-Assad was not really made in Syria, but in southern Beirut and Donetsk. Without the physical crutches of Russia's air force and Iran's proxy muscle Hezbollah, he toppled when finally pushed.

Israel's brutal yet effective two-month war on Hezbollah probably did not pay much mind to Assad's fate. But it may have decided it.

Likewise, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, 34 months ago, likely considered little how few jets or troops it might leave Moscow to uphold its Middle Eastern allies with. But the war of attrition has left Russia "incapable" of assisting Assad, even President-elect Donald Trump noted on Saturday.

And indeed Russia's Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov cut a weakened figure this weekend, saying: "What is the forecast? I cannot guess. We are not in the business of guessing." These are not the words of a steadfast and capable guarantor, rather those of a regional power seeing its spinning plates hit the floor.

Iran has been wildly hamstrung in the past six months, as its war with Israel, usually in the shadows or deniable, evolved into high-stakes and largely ineffective long-range missile attacks.

Its main proxy, Hezbollah, was crippled by a pager attack on its hierarchy, and then by weeks of vicious airstrikes. Tehran's pledges of support have done little so far but result in a joint statement with Syria and Iraq on "a need for collective action to confront" the rebels.

The Middle East is reeling because ideas taken as a given – like pervasive Iranian strength, and Russian solidity as an ally – are crumbling as they meet new realities.

Assad prevailed as the leader of a blood-drenched minority, not through guile or grit, but because Iran murdered for him and Moscow bombed for him.

Now these two allies are wildly over-stretched elsewhere, the imbalance that kept Assad and his ruling Alawite minority at the helm is also gone.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments