Postgraduate trainee doctors deserve better

The Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) degree is a five-year-long undergraduate course filled with struggles and hurdles. After being thoroughly drilled to sit for four professional exams on various medical subjects and a year of mandatory internship in their respective medical colleges, students then get the license to practice medicine in this country. Post-MBBS is a land of tough competition as there is a wide disparity between undergraduate seats, jobs available for only MBBS doctors, and postgraduate opportunities. Even the recently published 43rd BCS results had health cadre positions numbered in the hundreds only.

With odds stacked against them in government jobs and in hopes of receiving a specialised postgraduate degree, many graduates attempt the FCPS part-1 exam under the Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons (BCPS) or for an MD/MS degree under Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU). Although these degrees vary in syllabus according to subject and speciality, they all offer specialised training for three to four years and, on paper, some amount of remuneration. This is where the trouble begins.

Postgraduate trainees form the backbone of tertiary and specialised medical institutions in this country. But the compensation they are offered in return is not satisfactory, to say the least. They are the lowest in South Asia – and the payment sees no systemic yearly increment as in other countries such as Pakistan. Before 2023 the amount was a meagre BDT 20,000. After peaceful protests, the wages were increased to BDT 25,000. A slight improvement, yet in today's unfavourable economy, it remains very insufficient for postgraduate trainee doctors to sustain a healthy way of living.

Nazmush Shakib Bappi, a Postgraduate Trainee Doctor from Sir Salimullah Medical College, echoes the sentiment carried by nearly all in his position.

"By the time we enter our postgraduate trainee phase, most of us are over 26. Some are married and even starting families," he says. "How are we supposed to manage a family, manage our own expenses, and pay for our expensive exams – each of which cost north of Tk 13,000 – with that money?"

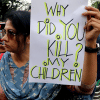

In the current economy, it is quite impossible for a junior doctor to sustain themselves let alone their families with such a low income. To add to the list of problems, the wages are disbursed once every six months. The recent protests for better wages by postgraduate trainees reflect years of neglect and the lack of long-term planning in terms of budget allocation to the health sector.

Mobarak Hossain, spokesperson of the United Medical Organizations of Bangladesh (UMOB), sheds light on the nature of their protests, "The Doctors Movement for Justice (DMJ) and UMOB have jointly worked to organise postgraduate trainees and protest in a peaceful manner. From our end, the demand was for a remuneration of Tk 50,000 or equivalent to a ninth-grade government employee payment which is what BCS appointees to postgraduate programmes under BSMMU and BCPS receive. But the interim government has communicated its limitations. The allowance has been set at Tk 30,000 with promises to increase it up to Tk 35,000 after July 2025."

He also said that the announcement had not met their expectations, and it was difficult for them to accept it. Considering the current woes the country is going through, postgraduate trainees have reluctantly withdrawn from the present strike and have rejoined their posts.

However, even with the increase in wages, is the allocated amount enough? Will the struggles simply subside? For Habibur Rahman, a postgraduate trainee from Chittagong Medical College, the reality still looks grim.

"I have to put my family through a lot of trouble just for this postgrad trainee course. The burden of these five years can be excruciating sometimes. And what many don't realise is that this period is an investment not just for us but for the government as well. They benefit directly from supporting doctors who are highly capable in their fields. If we have all the medical resources right here in Bangladesh, people won't have to go to other countries to seek treatment. The fact that this training period is so rough is part of the reason why the medical field has seen so many problems," he said.

The issues here are deep-rooted, and addressing them will require time and effort. In our country, the road to building specialised doctors is a very difficult one. If a doctor has to stress over money, the atmosphere it creates is not ideal for doctors to carry out their responsibilities.

To add to the list of troubles, many doctors have also cried out about the issues related to postgraduate trainees not being allowed to attend private practice chambers. If they are caught doing so, they are not paid their wages. According to Nazmush, "In our current economic landscape, this makes living a normal life extremely difficult with our meagre wages. Despite it, some doctors attend chambers in peripheral regions of Dhaka, working long shifts just to make ends meet."

And while long working hours are by no means unheard of in the medical profession, postgraduate trainees reportedly have to work an average of 60 hours a week. With these working hours, a payment of even BDT 35,000 might seem too low. Yet, our trainees are expected to deal with it, with many of them living in debt for long stretches of time. The onus is on the system to treat our doctors better, and on us not to laugh it off when they stand in protest.

Habibur recounts the most recent protests and how it was received, "Many have said we are attempting to conspire against the current government when the reality is that our efforts long precede this current regime. Some media outlets have also dismissed our efforts, which has been disheartening to see."

The truth is that for most people who visit a government hospital, it is more likely that they will be attended to by one of these trainees than a professor. With our current healthcare infrastructure and the huge number of patients attending hospitals every day, the functionality of the system unfairly hinges on these postgraduate trainees working long hours for low wages. It is important that we do not dismiss their struggle.

Mehrab Jamee is an activist at Sandhani, a fifth-year medical student at Mugda Medical College, and writes to keep himself sane. Reach him at [email protected].

Raian is a poet, a final year student at North South University, and a contributor to The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments