Trump's tariff war: How Bangladesh can mitigate its economic impact

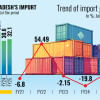

In recent years, the Bangladesh economy has weathered three major external shocks: Covid, the Ukraine War, and the July uprising. Now, another storm is brewing on the horizon. The first three came without any warning. The new one coming is Trump's tariff war. It is not entirely a surprise, and the country has had enough time to prepare for it, but its impact on commodity prices and the taka/dollar exchange rate is yet to be seen as of the first week of April.

Bangladesh is a "small country." And I do not use the adjective "small" in terms of the size of its population, nor regarding its influence on regional politics. Bangladesh is characterised as a small country in technical terms, in the parlance of the "theory of international trade and finance." Why so? Because our terms of trade and foreign currency exchange rate are given, or determined by external forces beyond our control.

Since taking oath in January, US President Donald Trump has made raising tariffs on foreign goods a cornerstone of his foreign policy as well as domestic policy. During his first presidency, Trump's goal was to reduce US trade deficits. This time, he seeks to punish Canada, Mexico, and China, putatively for sending drugs and migrants to the US. It might seem that a small country like Bangladesh may escape the wrath of this misguided policy.

Bangladesh, as we all know, does not export drugs or send illegal migrants to the US. As a small country, we are able to buy and sell as much of our imports and exports, respectively, without any impact on the price of goods in the global market.

In the realm of foreign exchange, it is a little more complicated. A small country's economy and trade volume are generally too small to have a significant, immediate impact on the global foreign exchange market, or the taka's exchange rate against the dollar, which is the world's reserve currency. But the government tried to keep our exchange rate pegged at a high rate.

A rise in tariffs, or a threatened rise, will lead to volatility in the foreign exchange market. Bangladesh's foreign exchange rate was considerably overvalued in the past, and under the interim government is easing towards a market-based exchange rate regime. The effect of growing unease among traders is evident in the recent rise in the price of gold in Bangladesh.

So, at first sight, it may appear that Bangladesh has nothing to fear about the latest round of the tariff wars. But is that really so? Emboldened by the positive outcome of the tariffs levied on China during his first presidency, Trump is escalating the war and is now handcrafting several variations of import taxes to serve his purpose. These fall into three categories: a) basic tariffs; b) reciprocal tariffs; and c) secondary tariffs.

Basic tariffs are used to raise the cost of imported products. They can be applied uniformly across the board, but some countries gain exemptions. Reciprocal tariffs are imposed in retaliation for tariffs levied on US exports. If Bangladesh imposes tariffs on cotton imports from the US, it could face some retaliation in the future.

Trump is now opening up another front by talking about "secondary" tariffs on specific countries and their exports. Venezuelan and Russian oil are the immediate targets, and any country that imports petroleum products from these countries could face secondary tariffs. For example, Bangladesh imports Russian LNG and could face additional tariffs on its exports to the US.

In sum, Trump's tariff actions could lead to an all-out trade war or deepen the ongoing chaos. The European Union announced it has a "strong plan" to retaliate in response to US tariffs if "necessary." The US could target wheat exports from Russia. Bangladesh may need to seek alternative sources for its wheat imports from Russia and face higher prices as a consequence. The White House also raised the possibility that the Trump administration will factor in non-tariff barriers that countries raise against the US. Non-tariff barriers include sales tax and VAT.

Bangladesh, among others, counts on the US as a premier destination for its garment exports and relies on a stable taka-to-dollar exchange rate as a linchpin of its external trade. After the US raised its tariffs on foreign goods, and threatened to use tariffs as a tool of its foreign policy, or as a "bamboo stick," Bangladesh and countries in a similar situation have reasons to feel caught in the crossfire.

While no place is truly insulated from global economic problems, some regions and economies are more resilient and have better tools to manage shocks than others. But the interconnectedness of the global economy means that even seemingly isolated areas can be affected.

While Bangladesh's products are not yet directly affected by the recent tariffs, continued economic uncertainty will upend financial markets. We have to keep an eye on the timing. As always, Bangladesh can benefit from the "migration" of investment and factories from China. The 35 percent tariff on RMG originating from China provides an opportunity for Bangladeshi exporters to increase their market share for this commodity.

We can learn from Vietnam, which is in competition with Bangladesh in some spheres but also enjoys a symbiotic ecosystem in others, and appears to be taking countermeasures to mitigate the effects of some of the possible turbulence in the global economy.

The New York Times, in a report entitled "How Trump's Tariffs Could Reorder Asia Trade and Exclude the US," provides some interesting possible outcomes of the tariff war. The Asian Development Bank is expecting a positive turn because supply chains can become more regional, and if countries are open to trade and investment among themselves, then there's a measure of safety or protection.

First, we could provide a welcome mat to Chinese firms and other companies trying to avoid the US tariffs. Secondly, Bangladesh can look at Asian markets as an alternative to the US and EU. Finally, Bangladesh may form trade partnerships with countries in the region.

The beneficial impact of US tariffs on Chinese goods may cancel out if the former raises tariffs on our exports now or in the aftermath of our transition from LDC status next year. Currently, US tariffs on Chinese garments might not boost our exports since these are non-competitive items, but Bangladesh will still be able to create an edge. To do so, it needs to enhance enterprise-level productivity, streamline trade facilitation, and improve compliance.

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and currently employed at a nonprofit financial intermediary in the US. He previously worked for the World Bank and Harvard University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments