Lima's ballot, Dhaka's echo: Vargas Llosa's political foray

In the brittle dawn of 1990, as Peru's economy haemorrhaged and Shining Path guerrillas carved their nihilism into the Andes, Mario Vargas Llosa, a man who had spent decades wrestling dictators and desire onto the page, staged a rebellion not with words, but with a ballot. His presidential campaign was a surrealist subplot ripped from one of his own novels: the writer as Don Quixote, tilting at the windmills of hyperinflation and terror, his lance a manifesto titled Liberty.

For Dhaka's readers, where poets once inked revolutions into being, this moment hums with kinship. Think of Rabindranath Tagore, who mistrusted nationalism even as he anthemed it, or the Bangladeshi bards who distilled liberation into verse. Vargas Llosa's crusade, a failure that seeded literary triumph, whispers a question: can stories outlive the frailty of those who write them?

The campaign as a novel

The streets of Lima in 1989 throbbed with a dissonant energy. At Vargas Llosa's rallies, crowds chanted "¡El escritor! ¡El escritor!"—"The writer!" as if they were summoning a fictional hero, not a candidate. Here was the author of The Feast of the Goat, a scalding portrait of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, now vowing "a government without caudillos." His platform, a cocktail of Thatcherite economics and Enlightenment ideals, clashed with Peru's left-leaning intelligentsia. Critics jeered at his polished Europhile demeanour: how could this Parisian novelist, with his tailored suits and Cartesian logic, preach austerity to Lima's pueblos jóvenes? Yet, his warnings about opponent Alberto Fujimori—"Democracy is not a lottery!"—carried the grim foresight of a tragedian.

In Dhaka, this arc echoes. Consider the intellectuals of 1971, whose pens sketched utopias only to watch them warp in the kiln of statehood. Vargas Llosa's campaign was equal parts hope and hubris. Years later, he'd muse, "I entered politics to prevent Peru from becoming a dystopia. I exited to write about the one that came anyway."

The alchemy of defeat

By April 1990, the plot twisted. Fujimori, the political outsider, trounced Vargas Llosa. The novelist retreated to his study, his manifesto ash. But from that wreckage rose Death in the Andes, a 1993 novel where Peru's mountains swallow soldiers and myths alike. Here, the Shining Path's savagery isn't a backdrop—it's a character, as vivid as any despot he'd skewered before. Defeat had honed his gaze; no longer the pedant of policy, he became a pathologist of power. His prose dissected the rot beneath ideology—how fear curdles into fanaticism, how dogma devours reason.

When Fujimori dissolved Congress in 1992, morphing into the autocrat Vargas Llosa had foretold, life pirouetted into art. The writer's revenge was not in office but in outliving the tyrant with a story. In Bangladesh, where the poetry of '71 sometimes stumbles against the prose of governance, this resonates. Liberation's lyricists know: the pen's power lies not in ruling but in refusing to relent.

The democracy of stories

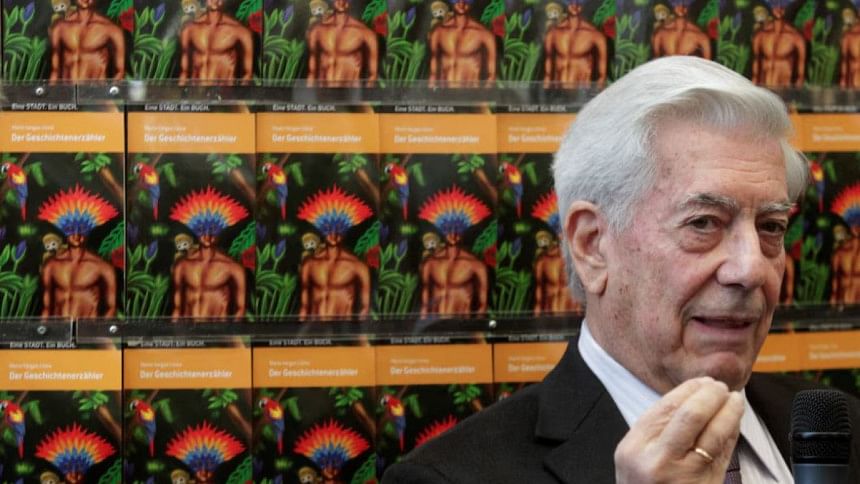

Long before his presidential gambit, Vargas Llosa wrote The Storyteller, about a man who vanishes into the Amazon to become a tribal narrator. It was a metaphor for his creed: storytelling as democracy's oxygen. "Fiction doesn't dictate. It questions," he insisted. His novels—torn between Lima's grit and Parisian salons—bridged continents, much like Dhaka's diaspora, forever suspended between roots and flight.

He Latin-Americanised the European novel, grafting Faulkner's fractures onto Andean soil. In The War of the End of the World, he chronicled a 19th century Brazilian uprising, not as history but as a fever dream of faith and ruin. For a region stalked by caudillos, his work was a vaccine: literature as fire, spreading "discontent," as he put it.

Why Dhaka listens

In a city where rickshaw pullers hum Nazrul and tea stalls debate Tagore, Vargas Llosa's paradox feels familiar. His failed presidency reminds us that art might lie not in the throne but in the echo. When dictators fall and policies fray, stories endure—the last, truest democracy.

In The Feast of the Goat, a dictator's autopsy reveals cancer gnawing his liver. Vargas Llosa, forever the surgeon-novelist, knew: literature dissects the malignancies that politics masks. Dhaka understands. Here, writers have long been haunters, their ghosts lingering in alleyways and assembly halls. The lesson isn't that artists should shun power, but that their rebellion is deeper, quieter—a whisper that outlasts the shout.

Zakir Kibria is a writer and policy analyst. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments