A primeval, timeless phantasm

How does one write about history? Certainly, there is the straight-forward, head-on approach, where a historical period is confronted directly by populating it with historical/fictional characters and portraying the times through their eyes. I'm not one to disparage this tactic. Crutch Er Colonel (Mowla Brothers, 2009) is a good example, and it certainly gives one a peek into the turbulent times post-71, a much-needed peek that puts a lot of our inheritance into perspective. The Magic Mountain (Secker and Warburg, 1927) is one of my favorite novels, and through its mixture of allegory and trenchant socio-ideological critique—beyond giving us an understanding of the ailments of Europe that led to the first world war—it also touches on universal themes such as love, societal progress, and time.

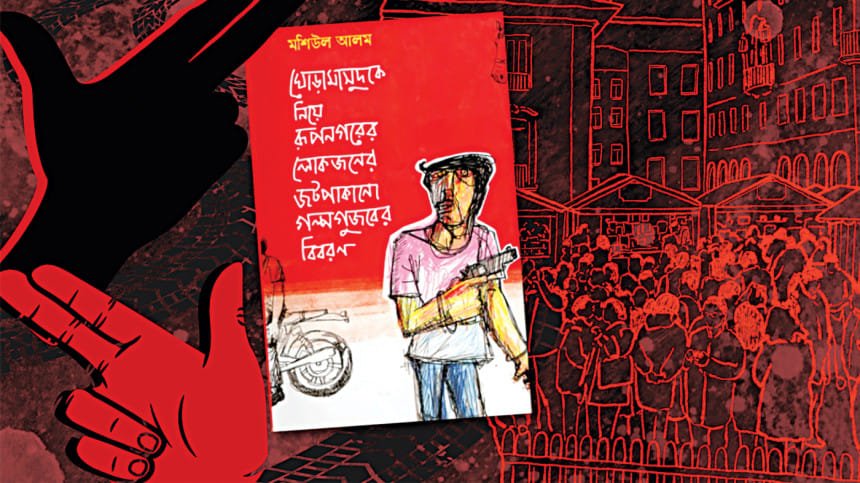

But when it gets right down to it, what differentiates one historical period from another? For context, what are the primary differences between 1971 and something recent such as 2024? The specific circumstances can be different, but it has always appeared to me that the primary agents of history are the same, and it is through focusing on these agents that we can gain a deeper understanding—something that hopefully will let us stop the cycle of time from repeating. Mashiul Alam seems to agree, and in his Ghoramasudke Niye Rupnogorer Lokjoner Jotpakano Golpogujober Biboron—he takes a macro-level perspective to examine the history of Bangladesh—a period primarily spanning the rule of Ayub Khan, 1971, Sheikh Mujib, Ziaur Rahman, Ershad, and the successors of Mujib and Zia, finally stopping in the final years of BNP's rule in the early 2000s when the fear of crossfires were at an all-time high; when the fear of criminals seemed unassailable. In doing so, Alam has focused on a number of agents when it comes to the history of Bangladesh; particularly, how the people in power have always used the people of this country as sheep, and how this power has always been ineluctably linked to violence.

From the title of this book, it should be clear that the novel focuses on the titular Ghora Masud—a government sponsored criminal who has been a sort of a boogeyman for the people of Rupnogor from time immemorial. The title also suggests that the novel will focus on how the people of Rupnogor talk about Ghora Masud, but a few chapters in and it becomes clear that the people of Rupnogor talk about things besides Ghora Masud as well—conversing about the charisma of Mujib and then jumping onto how he celebrated his birthday with an insanely huge cake when the nation suffered from a famine, conversing about the bravery of the local freedom fighters and about how they took money to facilitate the release of a Rajakar, conversing about how criminals in the town used to maintain a certain decorum before they got backing from the government, etc. Through such colorful, multifaceted discussion, the people of Rupnogor are certainly portrayed as a diverse, complex bunch—with their admiration for criminality on one page and their appeals to religion in the other—and the book can certainly be read as vivisection of a small community in the face of greater social and political changes, the community acting as stand-in for myriads of communities like this throughout Bangladesh, but in my opinion, in order to make the most out of the book, one has to take this reading just a bit further.

So, how does one write about history? What Alam does particularly well is not affording greater importance to one historical period over another. By taking a macro-level perspective and a large data-set, he is able to examine a huge swathe of history all at once—identifying the motifs and repetitions to strike at the primary agents. What he stumbles on is something that should be apparent to anyone who casts a somewhat objective, unbiased glance towards the past: no matter which side wins, the fate of the people scarcely ever changes. It doesn't matter if it's Pakistan or Bangladesh that's calling the shots, it doesn't matter if it's Awami League or BNP or the decades of military dictatorship we've slept through: the structures and the mechanisms through which power is yielded and exercised in Bangladesh never change; on the contrary, whoever comes into power becomes wholly integrated into this infernal process. This manifests in the narrative with Ghora Masud sometimes supporting Awami League, sometimes supporting BNP. We're also shown the power of hindsight in softening the rougher edges of power: the people of Rupnogor oftentimes look back fondly on the rule of Ayub Khan, sometimes they go back to praising Ziaur Rahman (while commenting on his abuse of power in another page).

There is scarcely a sense of continuity in the novel; the structure eliminates any sense of temporality, showcasing the people of Rupnogor living in a nebulous, muddled sphere that is void of memory. They simultaneously talk about the past, present, and future. They repeatedly discuss the same things—sometimes fondly, sometimes with bitterness—but they almost never succeed in drawing any conclusion from their discussions; they seldom succeed in maintaining a uniform, cohesive memory of history and thereby in making informed decisions. Their memory is circular, continually self-effacing and incomplete—touching on one of the most important and pitiful facets of history: regular people living through history like zombies. Sure, some are aware of the greater forces at work; some are even able to profit from the chaos. But for most people, history is like the tide of a downstream river; it takes up all their energies just to keep their head above water. Beyond that, most don't even make an attempt.

This, in my opinion, is the genius of Ghoramasud—how the non-linear, almost elliptical structure paints an insightful, trenchant portrait regarding the flow of time and history; how it gets to the root their agents and dissects the relationship between regular people and history; how it arrives at universal, fundamental truths that make the book appealing for not only readers in Bangladesh, but readers in general. Sure, the characters and plots aren't that memorable, and this means that the truths Alam has stumbled upon here lack that personal connection to make them seem wholly important to life (one could always argue that political truths in general are impossible to portray that way, but here I would again invoke the majesty of The Magic Mountain). But what Alam has done here is he has constructed a sort of primeval, timeless phantasm that forces people to think. In a country where a lot of writers are afraid of asking the big questions, I think that counts for a lot

Nafis Shahriar is currently working in the Ed-Tech space.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments