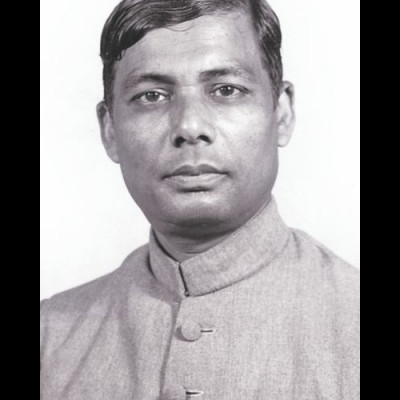

A tribute to Jasimuddin

And when old words die out on the tongue, new

melodies break forth from the heart; and where the

old tracks are lost, new country is revealed with its wonders.

−Rabindranath Tagore, Gitanjali

As old Greece had its Iliad and Odyssey and old India its Mahabharata and Ramayana, so modern Bengal does its Nakshi Kathar Math and Sojan Badiar Ghat. Good old great poems of the Ionian and Indian peninsulas, as everyone knows, are epics. And our two modern poems, however, belong to the genre of things known as ballads or sagas if you will. They are significantly named for a peasant society: Math and Ghat, i.e. field and wharf, in that order. But they are two, one almost says twin, ballads of modern Bengal, a country of two (or more) rivers, of two (or more) communities, a country that is no more, or almost no more. And Jasimuddin (occasionally 'Jasim Uddin' in a manner of rendering in English) is their author. Let us say a few words about the poet before turning to the poems themselves.

Jasimuddin was born on a very convenient date, namely January 1, 1903. It may be perhaps more of a legend than real. His place on earth is however less prone to legendary treatment. Tambulkhana, in Faridpur, is a lesser village where the poet was born. It is some eight miles off Govindpur, the village on his father's side where he grew up. 'I had been born and brought up,' to put it in Jasimuddin's own words, 'in a village populated entirely by cultivators, and the folk songs were in my blood.' Jasimuddin then did not have to look further up than his own folks for his motifs, fields and wharfs. Jasimuddin's work is about the folk, as Verrier Elwin said it many years ago. 'I do not know whether The Field of the Embroidered Quilt can be classed as folk-poetry, but it is obviously poetry about the folk.' It is in fact a little more than that as we will presently see.

Dineshchandra Sen, Jasimuddin's early mentor, too wrote: 'I consider Maulvi Jasimuddin's Nakshi Kathar Math as one of the best lyrical poems in our language.' Writing three quarters of a century later the present writer would likewise concur. 'Its pastoral descriptions and a unique array of picturesque scenery introduced off and on in this love tale,' reasoned Sen, that grand old chronicler, 'will acquaint one with the purity, strength, devotion and poetry of Bengali domestic life.' 'The author's penetrating insight into the very character of our masses, his talented grasp of the characteristics of feminine feelings,' Sen remarked, 'have invested the poem with life-like presentation of the moral and cultural traits of Bengalis.'

'In fact,' Sen went on saying, 'I do not know of any modern poets who have such an intimate knowledge of this beautiful land of ours.' Why on earth, one wonders. Western civilization or the new education, its grand trope, spreading out from Calcutta, 'reaching the remotest country town where any middle class inhabitant aspired to be educated,' belonged to the town and its denizens, the middle classes. It brought many challenges along with the well churned out responses.

'It created its own culture and its own literature,' Jasimuddin wrote in the 1950s, 'with themes and rhymes which were partly European in spirit, and partly linked up with the upper levels of culture in other parts of India. Almost every literate man's eyes looked westward. The songs of the middle classes were sung to the accompaniment of modern European instruments such as the violin and the abominable portable harmonium, and the traditional instruments of Bengal fell out of fashion.' 'In the dazzling light of the western sun,' as Jasimuddin's own metaphor has it, 'the little earthen lamps with which people used to see into the corners of their own rooms had lost their power of illumination. They look out at the whole world, but the beautiful things which lay at hand were hidden from sight.'

By the turn of the twentieth century, Jasimuddin laments, there was hardly anyone around to dare turning the tides about. Even Rabindranath Tagore, for all his fame, was writing for the middle-classes. 'He hesitated to present the old tunes in their original form to people who would have despised them.' 'What he did,' Jasimuddin noted, 'was to create 'a kind of sophisticated version of them.'

It is at this conjuncture that Jasimuddin finds himself in the middle of a small group of middle class ballad-collectors under Dineshchandra Sen. Jasimudddin was already there before he would be looking out with Sen to find out his own passage to modernity. Let's get it from the horse's own organ: 'To me, unlike [Dineshchandra] Sen, the tunes meant even more than the words: they embodied the meaning of the traditional life I loved. They made me mad with their beauty and power, and I was set on making the reading public understand what was in them. It was not only for the sake of the reading public; it was a question of preserving the life of the tradition itself.'

Thus speaks our modern poet out loud: one awaited the poet who will have loved the new learning but will give no short shrift to old treasures either. 'The old songs and ballads were too long-drawn-out for the new time-conscious man to spend hours listening to them: they repeated themselves interminably and were full of ideas and incidents unpleasing to the modern mind. Yet there was so much in them that might have been preserved. Had there been any great mind with a touch of poetry, someone who loved the new learning and loved his country's past, it might have been possible to save both. The old songs and tunes, still alive among the people could have been collected and revised, purged of their corrupt and outworn elements and recreated. They might have become a link, making the people's mind intelligible to the educated man and bringing the new outlook down to the consciousness of the illiterate.'

In the ballad Sojan Badiar Ghat [rendered Gipsy Wharf in English] modernity already arrived in the guise of communal riots. Sojan, the lover, is a Muslim man and Dulali, his beloved, is a Namasudra woman or a Hindu of the 'scheduled' caste in the colonial register. As Barbara Painter, translator into English, notes, 'Sojan and Dulali were destined from the beginning to be ill-starred lovers. It is not acceptable for them to marry outside their fellow religions and elopement into the forest seems the only solution. For some time they live happily in their forest cottage, but eventually Sojan is caught and imprisoned. Dulali is remarried by her orthodox parents to a farmer in a distant village. When Sojan is released from jail he finds his family gone, his village disrupted and his beloved remarried. In despair he joins a band of wandering water gypsies.'

Further: 'In his wanderings with the gipsies, Sojan has been living in the hope of finding Dulali. When he finds her in the water-side village happily remarried, she at first rebuffs him for seeking her out. Then her love for him proves too strong. She steals away in the night, and rejoins Sojan, only to find that his grief at her cold reception has led him to take poison. She takes poison too and the lovers die like Romeo and Juliet.' 'The two communities, however, do not embrace each other because of this tragedy,' thus concludes Barbara Painter her melancholy introduction to the UNESCO edition of the poem in 1969.

Relations between the Muslim and the Namasudra communities in certain districts of lower Bengal, including Faridpur, have been tense since the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1933, when Sojan Badiar Ghat saw the light of day, things could not have been worse. The question of communal award was taking its toll. Times could not be more unpropitious in Bengal to depict Hindu-Muslim affairs in such terms. It is a pity to learn that Jasimuddin was accused of nurturing a communal (i.e. pro-Muslim) bias, in writing this ballad. Many, including the eminent Suniti Kumar Chatterjee and the learned Narendra Dev, reportedly joined the fray. Such misunderstanding was in fact symptomatic and was part of the times. Jasimuddin's ballad of the gipsy, in retrospect, seems to have been a prophetic saga. The partition of Bengal was anyway not far away, a decade and a half at most.

Jasimuddin's political outlook is not naïve. On the contrary, it was a remarkably 'communitarian' worldview that he embraced. His was emphatically not a 'communal' outlook at all. He will be the last man to disregard ruling contradictions among the people. He in fact grasps it well how trouble might arise out of nowhere when the milieu is always already brittle, as was the case of a quarrel at the Muharram festival in the village of Shimultali. Jasimuddin however misses no opportunity to identify the role of the privileged classes, personified aptly in the Naib, or rent collector for the bhadralok Zamindar in stirring up the riots.

Although historians of modern Bengal give it habitually a short shrift, one ignores the communal tension at a great cost to their professional integrity. Since the end of the 19th century relations between the two communities in southern and south central Bengal had been very tense. 'There was always a strong under-current of ill-feeling and whenever petty incidents occurred between individuals, large numbers on both sides would be ready to vindicate the honour of their respective communities,' writes Sekhar Bandyopadhyay.

Communal collisions were legion between circa 1911 -1947. But their configurations changed midway quite palpably for those who have an aptitude for analysis. The Muslim-Namsudra relations were 'seriously agitated during the convulsions of 1911 in Jessore-Khulna'. As Sekhar Bandyopadhyay enumerates, two years later in 1913, a dispute culminated in violence at Silna, a marketplace near Gopalganj. Likewise, in the same year 'there was also a disturbance at Tarail in Kasiani police station. And then during the Non-cooperation [also the Khilafat] movement a political dimension was added to the already embittered relationship.' It continued till 1921-22. In the high tide of Non-cooperation movement, the Muslims and the Namasudras found themselves on the opposite sides of the fence.

Things overturned themselves, however, by 1925-26. By then, when the Khilafat movement had died down, 'the two peasant communities were again coming closer, if not in Faridpur, then definitely in other surrounding districts, against the Hindu bhadralok and their nationalist agitation.' 'In Narail subdivision of Jessore the Muslim and Namasudra sharecroppers has already combined again under the leadership of Nausher Ali to demand two-thirds share of the produce from their caste Hindu jotedars,' notes Sekhar Bandyopadhyay. And this was to prove their undoing. 'The movement which continued for greater part of 1924-25 was dubbed by the Congress as communal and was repressed ultimately by the police.'

Jasimuddin had these convulsions in mind when he undertook his task. No individual, not even a poet of such integrity, would prove equal to these trends of the times. Until partition in 1947, the tides were not to subside. After 1947, on both sides of the fence, as they say, it's a different story.

REFERENCES

1. Jasimuddin, 'Folk Music of East Pakistan,' Journal of the International Folk Music Council, vol. 3 (1951), pp. 41-44.

2. Jasim Uddin, Gipsy Wharf, Barbara Painter and Yann Lovelock, trans. (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1969).

3. Jasimuddin, The Field of the Embroidered Quilt: A tale of two Indian villages, E. M. Milford, trans. (Calcutta: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1939).

4. Sekhar Bandyopadhyay, Caste, Protest and Identity in Colonial India: The Namasudras of Ben gal, 1872-1947, 2nd ed. (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015).

The writer is Professor at General Education Department, ULAB

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments