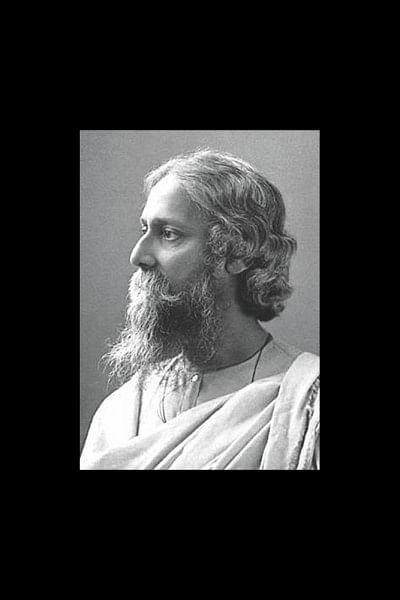

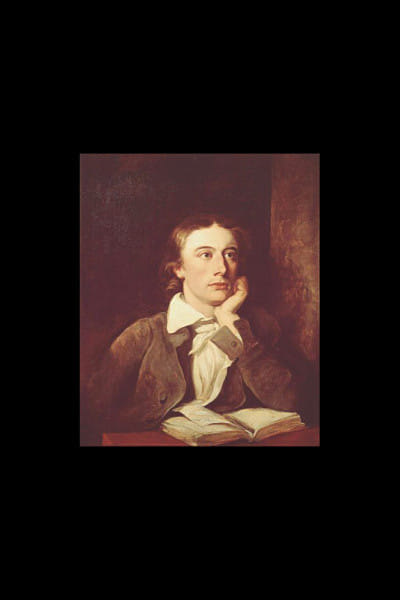

Tagore and Keats

John Keats (1795-1821) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), two great idealists, belonged two different times and places and did not use the same language, but astonishingly enough, possessed similar types of sensibilities and idealistic vision. Their bhakti (devotion) and spiritual illumination or maya had in it deep understanding of life. The frailty of love, poignant morbidity, insatiable passion, doubt on ephemeral life and disharmony of the world filled up their oeuvres with profound agony. So they leave the mundane life and take refuge to imagination. But eventually they go through some kind of metamorphosis and come back to accept the realities of life.

As a poet emphatically that of nature and creative imagination, Tagore starts his divine journey infusing his ideas with floating clouds:

'My mind is a companion of the clouds

Flying into the horizon, in the infinity of space.'

Beauty, to Tagore is an illumination, the state of attaining the ultimate spiritual bliss. Infinite being expresses His beauty mixed with nature; Tagore states it in 'Sadhana'.

Keats shows psycho-aesthetic interest in 'To Fanny', an eulogy to his beloved Fanny Brawne. The poem is also mentionable for having Keats's signature spirituality:

'My muse had wings/ And ever ready was to take her course'

On the other hand, Tagore's famous lines 'Shimar Majhe Aushim Tumi'(Within limits you remain limitless) has become the byword for Romanticism. Tagore is bemused by the feeling of unseen:

'You, the formless, engage in a play with form

Endowing me with your beauty which is so mellifluous.'

No-one can offer such extraordinary lines on imagination as Keats in 'Endymion'. It is the stamp of his romantic imagination. Silence here becomes music:

'To his capable ears. Silence was music from the holy spheres.'

It is no less than obvious that Tagore and Keats possess an innate instinct to fly high to be merged into the infinity to experience eternal bliss.

In fact, Keats's fancied mental flight begins in 'Ode to Psyche', and eventually, in the 'Ode to Autumn' the poet comes back to materiality. In the 'Ode to a Nightingale', the elfish song of the bird cannot entice the poet anymore: 'adieu! The fancy cannot cheat anymore'

Later, In 'Endymion' Keats shows profound doubts about the falsity of his hollow vision. These lines stand as a proof of Keats's recognition of mortal realities:

'I have clung

To nothing, lov'd nothing, nothing seen

Or felt but a great dream!'

In the poems of 'Chitra' an eternal woman engulfs Tagore's whole existence as if he has found his most coveted 'Jibandebata' or the 'life-deity'. In many of Tagore's works rendezvous with the formless is his main interest.

Eventually, Tagore also has a somersault; in the poem 'Matir Daak' Tagore is not in love for the transcendental one but discovers joy and beauty in the real world. With a confident manner of withdrawal, Tagore allows reality and denounces deceptive imagination emphatically:

'It is merely an idle illusion

It is only a play of clouds'

Like Keats's evasive Nightingale, Tagore's bird's song becomes mute in 'Kalmrigaya':

'The garden looks arid,

The birds do not sing.'

Tagore confesses the inevitability of melancholy. Earthly truth gives a blow to his spiritual obsession. He shows strong stoical traits by accepting pains and death:

'There is sorrow there is death,

Yet there is peace, yet there is bliss.'

The most important message is served is that delight and melancholy or joy and sorrow are two inseparable parts of our lives. Sorrow and anxieties do not belittle the possibilities of life rather they are necessary for happiness's sake. Joy is not perfect or complete without acute feeling of sorrow. Likewise, Keats in his sonnet "Why Did I Laugh Tonight?" calls death the highest gift of life: 'Death is Life's high meed,'

In 'Gitanjali' Tagore accepts death as a fulfillment of life:

'And because I love this life, I know I shall love death as well.'

Tagore in his celebrated song-poem 'Poush' praises the beauty of Poush. Tagore like Keats in his hyperbolic adulation and gladness immortalise a bright Poush day which recalls Autumn of Keats.

'Poush calls you all to its festival-come, come away.

Miraculously, its baskets fill with ripe harvests this day!

Tagore's 'On the bank of Roop-Naran' shows the sharp transformation of the great thinker. 'I knew for sure this world's no dream/ and I learnt to love this harshness –it never betrays'. His thoughts are now devoted not to visionary flights but to harsh realities of life, and the focus and attitude show him reconciled to the real world he lives in.

Tagore on the way to muse acutely over life comes to know the purposes of joy and sorrow, beauty and decay, permanence and transience and attain a poetic Nirvana. As the grave confusion of Keats is over, there is a satisfactory reconciliation between imagination and reality, immortality and mortality, as well as idealism and materialism. Life may be short and perishable but is not insignificant, rather it is delightful and death is its fruition.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments