An end in sight for ultra poverty

In the last 15 years, Bangladesh has emerged as one of the champions of poverty reduction. Statistics suggest that during the last 10 years, the number of people living below the poverty line in Bangladesh has gone down from 25.1 percent to 17.6 percent. On the eve of the International Day for Eradication of Poverty, this number gives us a reason to pat ourselves on the back and feel proud of our achievements. However, a key question remains - is this achievement enough? If we continue at this pace, will we be able to eradicate extreme poverty from Bangladesh by 2030?

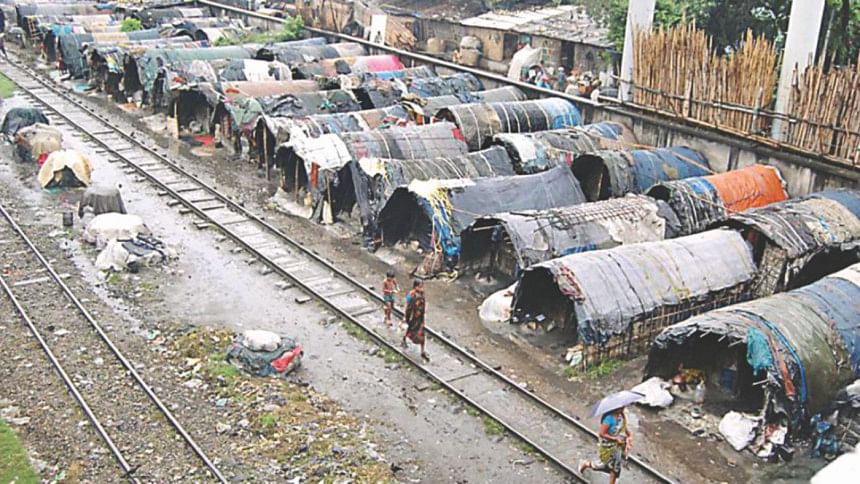

This year's International Day for the Eradication of Poverty is special because it comes at the heels of the adaptation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations. The most critical item of this agenda, as could be expected is, "End poverty in all its forms everywhere" by 2030. Because travelling the last mile is always the toughest, we cannot do it by following the same strategies, tools and path, which led us to success in the past. In spite of the seismic achievement in reducing extreme poverty by half since 2000, eradicating extreme poverty in the next 15 years will require carving a path out for the poorest of the poor – the ultra poor (those earning 70 US cents or less a day).

Traditionally, most social protection programmes target the destitute, and extreme or moderate poor. Similarly, traditional microfinance and livelihood development programmes target those who are poor as well as non-poor. This design has two limitations. First, social protection programmes designed to offer protection (for example, from hunger), fail to offer the ladder (for example, jobs or livelihood) to climb out of extreme poverty. Second, it doesn't recognise that the ultra poor require additional guidance. We found this particular group of people to be so poor and so weighed down by ignorance, ill health, and social exclusion, that they were unable to do anything significant with the microloan given to them. As a result, while this set of programmes may have helped a good number of people to get out of the poverty trap, they were not particularly useful for the ultra poor population.

After decades of trial and error, starting in 2002, BRAC began deploying a set of carefully sequenced measures tailored to the unique set of challenges faced by the ultra poor. A custom-built, two-year intervention included steps such as targeting by the community, productive asset transfer, weekly stipends, intensive hands-on mentoring on utilisation of resources, healthcare, saving and social integration. The carefully designed programme did not just look at economic growth but also their respectful social relations. At the end of the programme, participants were evaluated based on certain graduation indicators on social acceptance and economic prosperity.

The first results of the programme evaluation were astonishing. A collaborative study conducted by BRAC's Research and Evaluation Division (RED) and the London School of Economics (LSE), showed that over 95 percent of the targeted households graduated from ultra poverty, fulfilling the set of criteria. Improvements included, among others, a rise in livestock asset base by Tk. 11,000, even two years after the intervention ended. Since 2002, BRAC has scaled the programme and has graduated 1.5 million households out of ultra poverty.

These research findings and experience encouraged governments and NGOs in nine other countries - Ethiopia, Honduras, Peru, Yemen, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Ghana and Haiti - to replicate the model in their own countries. BRAC provided technical assistance in most countries and directly implemented the programme in Pakistan and South Sudan.

Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Poverty Action Lab ran six randomised controlled trials over a seven-year in six-countries with more than 10,000 poor households. The results were equally encouraging. The graduation rate ranged from 75-98 percent. At the end of the two-year programme, the monthly consumption of food had risen by around 5 percent relative to a control group. The value of assets had increased by 15 percent. Even more encouraging, when the researchers went back a year after the programme ended, they found that people were still working, earning and eating more.

After this successful adaptation of the graduation approach outside Bangladesh, governments, NGOs, and policymakers can be confident that they now have an adaptable, scalable, international solution to address poverty that is hardest to beat. This presents an incredibly exciting opportunity for the global community to think carefully about how new international aid programmes, government social safety nets, and financial service packages can be re-designed to reach households living in the very fringes of our societies, and create more effective impact.

Of course, BRAC's model is one among many and there must be many more experiments that took place in solving this seemingly impossible challenge of reaching the ultra poor. That's exactly why we need to engage in a broad-based dialogue both home and abroad to share our insights and experiences and design a new paradigm for fighting extreme poverty suitable for each country.

As a first step for that, this year, BRAC is co-hosting an international extreme poverty summit in the UK, along with London School of Economics looking at the evaluation results with international policymakers. From 2016 onwards, we are starting a process to organise a similar summit every year in Bangladesh in partnership with the government and other development stakeholders of the country. We hope that such summits with clear goals will become a collaborative platform for countries around the world to fight the menace of extreme poverty more effectively. With proven models like BRAC's globally recognised 'targeting ultra poor' programme, the opportunity to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030 looks more realistic than ever.

The writer is the Executive Director of BRAC.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments