Redressing an aberration

AT long last the last impediment to the implementation of the Land Boundary Agreement and the related Protocols has been removed. And one hopes that an irritant between the two countries will soon disappear with the complete implementation of the agreement. The only remorse is that we did not get to see the kind of reaction cutting across party line in this country as we saw in India. On the other hand there was the usual telling off between the AL and the BNP. It was foolish of anyone to have expected otherwise.

The Indo-Bangladesh border is the most convoluted border between any two countries in the world. Not only was it whimsically drawn, the person responsible to fix the borders seldom, if ever, ventured out of the cool of his room to see what damage his pencil marks, sometimes drawn under pressure, on the map of undivided India was going to wreak in the conduct of relationship between the newly born independent countries of the sub-continent.

Mr. Radcliffe, who could not have been very popular among the Muslims or the Sikhs given the difficult nature of the boundary issues thus created, was advised in 1947 to stay away from either of the countries after partition. A 2011 article in The Economist, addressing the enclaves issues in the two countries, entitled The land that maps forgot, refers to a 2004 paper titled 'An historical and documentary study of the Cooch Behar enclaves of India and Bangladesh', in which Mr. Whyte, in reference to the intractability of the boundary issues at partition, asks whether India is still "waiting for the Eskimo". When in 1947 Mr. Feroz Khan Noon suggested that Sir Cyril Radcliffe should not visit Lahore for he was sure to be misunderstood either by the Muslims or the Sikhs, The Statesman wrote: "On this line of argument, he [Sir Cyril] would do better to remain in London, or better still, take up residence in Alaska. Perhaps however there would be no objection to his surveying the boundaries of the Punjab from the air if piloted by an Eskimo." The reference to the Eskimo being made because the chance of an Eskimo piloting an airplane seventy years ago was as remote as the possibility of the confounded border issues between India and Pakistan being resolved.

Thankfully, the intractable problem that Bangladesh inherited after March 26 1971 is on the way to being resolved finally though not quite done and dusted. That being so, one may take the liberty of indulging in retrospection on the issue of the enclaves, whose origin is mixed in both fables and history.

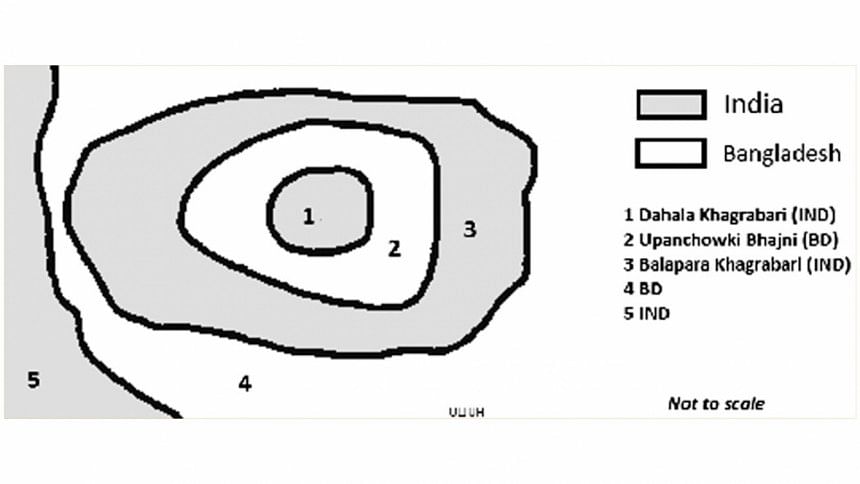

There are not only 162 enclaves measuring a total of 24,268 acres as per the agreed list signed in April 1997 at the level of Director General Land Record & Survey, Bangladesh and DLRS, India, there are 6,500 acres of land in adverse possession. And the enclaves also include about two dozen counter-enclaves (enclaves within enclaves), as well as the world's only counter-counter enclave -- a patch of Bangladesh that is surrounded by Indian territory…itself surrounded by Bangladeshi territory like in the sketch.

To say that the enclaves are an aberration would perhaps be an understatement, given the history of their origin and the indescribable misery that the people of the enclaves have suffered in the last sixty eight years. And the worst of the sufferings was not so much physical but psychological caused by having to live in a virtual state of statelessness.

But need they have gone through this for so long? My answer is no. And here are my reasons.

Swapping of enclaves was agreed in 1958 through the Noon-Nehru Agreement of September 10, 1958 which inter alia addressed the problem of Berubari as well of the enclaves and lands in adverse possession. Legal encumbrances prevented its implementation till the 9th Amendment to the Indian Constitution was made in 1960. The transfer of the enclaves between East Pakistan and Cooch Behar was scheduled for March 27, 1971. And we all know why that could not happen.

Therefore, Bangladesh, as an inheritor of all territories that constituted erstwhile East Pakistan and all such territory that deemed to have belonged to East Pakistan as a result of any bilateral treaties before March 26, 1971, had both ipso jure and ipso facto inherited the lands that were to come to it through such compacts which included the Noon-Nehru Agreement whose implementation was delayed by a force majeure. Therefore, even if a new agreement, as was the Indira-Mujib Agreement of 1974, was necessary in this regard, one wonders whether there was at all the need for foot-dragging for 41 years on the excuse of legal compulsions.

Here is a remark of a distinguished Indian diplomat in a recent article in the Hindustan Times following the passage of the LBA Bill in the Indian Parliament which reflects the Indian establishment's views. He says, "The 1974 Indira-Mujib accord was approved shortly by the Bangladesh parliament. India did not do so as the acquisition or surrender of any territory required precise determination of the territory involved." Some scholars argue that according to the "1966 Indian Supreme Court (Justice Gajendragadkar) judgement in the case Ram Kishore vs Union that the Constitution (9th Amendment) Act of 1960 was wholly unnecessary because a law reference to Article 3 would have been adequate to implement the Noon-Nehru Agreement of 1958." And the details were in the 9th Amendment. Even otherwise, 41 years has been much too long a time for "the precise determination of the territory involved."

The writer is Editor, Oped and Defence & Strategic Affairs, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments