Reimagining academia for students of the future

"Nothing pushes students to do their best work like a professor who takes pride not in his or her own accomplishments, but in helping others realize their potential"

-- Jason Dent

Recently I heard a rather bewildering story on teaching in higher education. Taught to depict a triangle as ABC, a student wrote PQR instead and suffered a significant deduction of points for "misrepresenting" a triangle! Horrific as this isolated story - perhaps even a fable - may be, there is a growing discontent against teachers, especially on how they relate to students and the methods they employ in their classrooms.

Being curious about this vital matter of student-teacher interface, I asked fresh young recruits in a teacher-orientation workshop to recount experiences of poor or ineffective teaching from their own past. Each of them had a story to tell. Here is a sampling of what they suffered:

* Teacher does not take classes regularly and has many excuses to be busy.

* Could not make the class interactive.

* Used the traditional lecture method and taught straight from the book.

* Did not have a clear idea of either content or materials.

* Course outline of the teacher was not up-to-date.

* Not approachable or friendly.

* Laughed at us if we could not answer; as if it was our fault that we did not know the answer.

* Would never answer questions and laughed at us for being so stupid.

* Displayed [preference] towards a particular group.

* Assessment system was questionable [especially its fairness].

* Went through all the slides without explaining the subject matter.

* Lectures were disorganized; no clear expectations were set.

* Discouraged students from asking questions.

* Not available during office hours.

* The exams required rote memorization of mundane/trivial facts and writing essays.

* Rigid, not open to ideas, and lost patience when questioned.

In this day and age, fresh graduates are telling us what academia should NOT be doing. Yet, unfortunately, many of the age-old practices prevail.Left unchecked, the quality of our students will automatically relegate them to the sidelines while the creative and demanding jobs will be left to be outsourced. Not surprisingly, a recent report suggested that Bangladesh already pays out over 5 billion US dollars to foreign workers who fill the middle to upper echelons. A large portion of our foreign exchange earnings are thus diverted from other productive ventures while our graduates languish and suffer. Is this state of affairs acceptable?

The larger questions that the above state of affairs elicits, also appropriately raised by the World Economic Forum1, is "How do we best educate the students of tomorrow? What we teach our children - and how we teach them - will impact almost every aspect of society, from the quality of healthcare to industrial output; from technological advances to financial services" … and much more. Two critical elements (and there are others) requiring serious attention are content and delivery.

Content (what to teach): Knowledge is not static; it has grown rather rapidly and will continue to do so at a faster rate. Unless the curriculums are updated - continuously - our students will be equipped with dated and obsolete knowledge and rendered non-competitive. Every academic unit, department, centre or institute offering an academic program must bear the responsibility of updating curriculum, the content of which must be crisp and relevant and for the times.

It must also be recognized that it may not be possible to offer the full menu of knowledge products to our students given contextual and resource challenges. Thus we must be selective. If this selectivity is driven by national priorities, aligned with pre-college stages,deliveredby competent teaching staff, and properly resourced, the value addition can be remarkable. Content selection also requires a collective conviction of all stakeholders that the best alternative is selected. Of the dizzying array of options, the choice of what to teach viaa vibrant curriculum must be pragmatic, pro-nation, and contemporary.

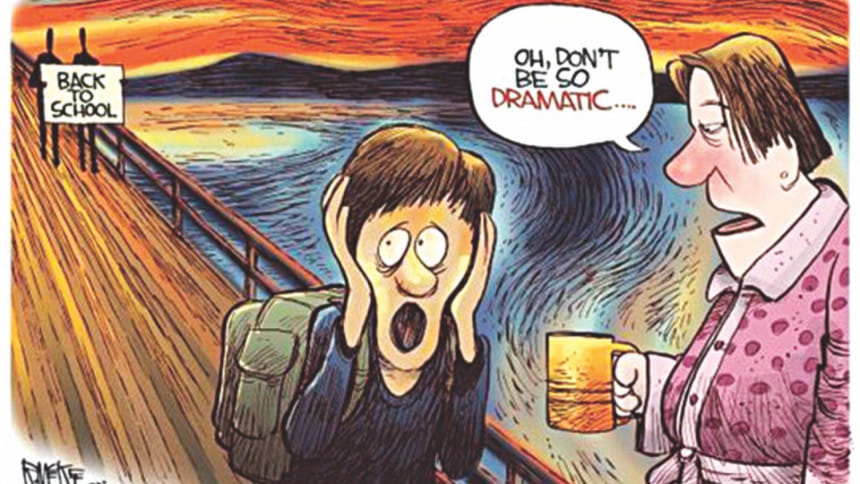

Delivery (How should we teach): Holding of students prisoners in cages (okay, classrooms)by unimaginative teachers must surely be done away with. According to researchers and educators, "Young people don't want to be passive learners: They are content producers, not just consumers. They communicate in different ways than older generations, in shorter bursts, and they are used to being a part of large networks that allow them instant feedback on their thoughts and ideas."

With changes in demographics, technology, globalization, etc., the world of pedagogy has also changed. Flipped classrooms, interactive approaches, group discussions, problem-solving, computer simulations, role playing, case analyses, introspective paragraphs, critical thinking, writing questions (not answers), research, and much more have been shown to be most effective in "reaching" students, not teaching them.

Dovetailing the above methods with students' new learning options, styles and expectations, especially in the context of new technology, social media, and alternate learning sources,means that the teaching-learning environment must change. Some believe that students of the future are less likely to be seeking a degree. They will come with a wide range of backgrounds, but specific skill needs.

Is academia thinking along these lines? It is thus vitally important to anticipate and prepare for the students of the future who will be very different from their predecessors. Unless the disjunctions with them are identified and addressed, educational institutions will be out of synch and fail to serve future generations. In fact, in today's technology driven world, it may be emphasized that the smart student has access to the world's knowledge systems. Teachers will only make themselves look foolish if they bring to class outdated and outmoded perspectives. Apparently, some still do!

In fact, according to Professor Anant Agarwal, "Technology is casting a spotlight on the innovation of massively open [online] courses, of dynamic new study options that are available to everyone, regardless of background or location" and may mean that "In the future, you could go to university having done the first year of content online. You could then come and have the campus experience for two years, before going on to get a job in industry where you become a continuous learner for the rest of your life. "Agarwal sees technology as providing flexibility, combined with instant online feedback, to vastly improve learning outcomes.

Disruptive innovations in education that combine methodology, technology, and organizational format for knowledge delivery are on the rise and will challenge or may even replace theuniversity of the future. Imaginative players, by meeting the needs of specific target groups, could potentially draw "customers" away from academia. In fact accreditation systems may also change to enable creative knowledge producers to package it in innovative and demand-driven ways and thus bypass academia. Lest academia is caught sleeping, it must also innovate.

In this milieu, the traditional teachers need to develop professional competencies beyond subject matter. Their academic attainments and content expertise may be substantial, but they may not be versed in the emerging pedagogical tools that can help shape modern students. Yet, when asked to sign up for professional development, many react predictably: they are loathe to sign up and their demeanor reflects a certain "I don't need to learn"haughtiness.

It is time to have a deeper dialogue on key two matters: what is the student of the future going to be like and how should academic institutions prepare to meet their needs.It will be important to involve, educators, employers, policy makers and students to work together and help shape the nation's knowledge needs and build effective and relevant knowledge systems.

With new thinking on the future university, a clearer role of higher education, continuous research, and technology integration, perhaps we will really begin to build world class knowledge systems.

The writer is Vice Chancellor of BRAC University and Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Pennsylvania State University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments