The problem with academic bureaucratisation

When an esteem-ed member of our university's syndicate board died recently, we requested the government for a replacement. According to Private University Act 2010, clause 17(e), the government is supposed to nominate an educator or a philomath for the syndicate. The response, however, was beyond our expectation, and quite telling of a silent "move" of bureaucratisation that is going to have a lasting impact, not only on academia, but also on our society.

Prof Shamsuzzaman Khan, the former President and Chairman of Bangla Academy, was on our Board of Syndicate at the time of his death on April 14, 2021. But a circular of the Ministry of Education dated January 7, 2021, showed that he had been already replaced by a certain Joint Secretary of the College Division. The Ministry was evidently waiting for his tenure to be over before breaking the news to us. The circular shows a long list of education ministry officials who will, from now on, represent the government in the category of renowned academics or philomaths in the syndicate boards of all private universities. Each joint secretary and additional secretary of the ministry has been assigned to five to seven universities.

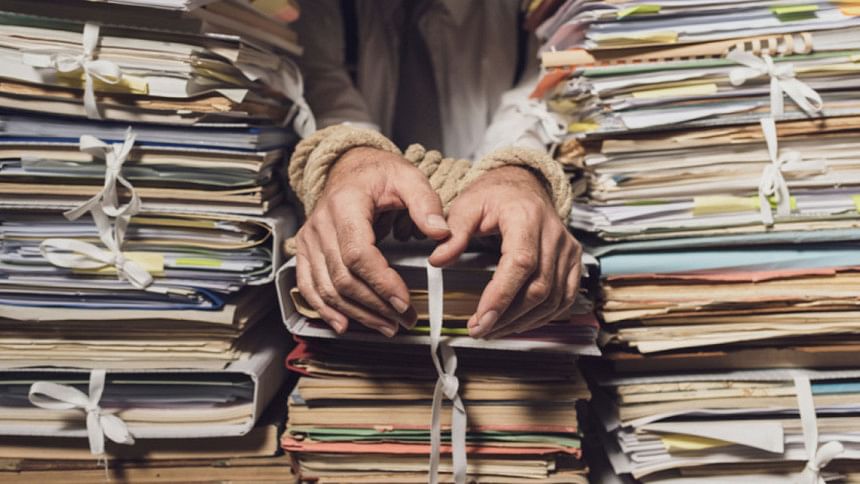

As someone who has been teaching for over 28 years, I have seen how the presence of a noted academic in the apex body allows a university to shape its academic policies and leadership. The wisdom and experience of senior faculty members is now being replaced by the paper chains of some professionals who are legendary for slowing things down. Besides, these officers already have a lot on their plates: they are responsible for millions of students in the secondary and the higher secondary system. How much time can these officers spare for the five to seven universities to which they have been assigned? How much orientation they have on the tertiary system is soon to be seen. Isn't there a government sanctioned grants commission to look after universities? I am sure all the designated syndicate members are brilliant officers with immaculate career records—but do they all qualify as "academicians or philomaths", as mentioned in the particular clause of the 2010 Act? Even from the government's perspective, if the intention is to have eyes and ears on the ground, this could have been better served by members of civil society who seem to have an affinity towards them. I am just curious what rationale there could be behind such a decision.

Already, with the introduction of quality assurance in the universities funded by the World Bank, we are noting the implementation of a bureaucratic system that suffocates academic freedom in favour of a greater centralised and hierarchical organisational structure that puts emphasis on top-down management, with decreased local autonomy for departments. Some cumbersome and intrusive procedures are introduced to monitor the paper trails of teaching and learning. University teachers are now required to fill out 14 forms for every course: Lesson Plan, Class Monitor Form (CR selection form), Class Attendance Sheet, Midterm Question Paper, Final Question Paper, Midterm Exam Scripts of low, average and highest score (checked, commented and marked), Final Exam Scripts of low, average and highest score (checked, commented and marked), Midterm Exam Attendance Sheet, Final Exam Attendance Sheet, Semester Course Report, Course Session Report, Make Up Class, Student Excused Absence Form and Course Closing Checklist.

I give you the long list to give you an understanding of the international bureaucracy that has crept into the local system. Bureaucratisation of academic institutions is a contentious issue. Somehow, we have been colonised with the idea of big data that can be converted into parameters needed for university accreditation and ranking. Unless we comply, we are told that our degrees won't be recognised.

The growing status of bureaucracy led me to a government project, titled, "Strengthening Government through Capacity Development of the BCS Cadre Officials (3rd Revised)". According to this project, between 2009 and 2019, the government spent a total of Taka 33,853.69 lakh on sending BCS officers for foreign Master's degrees in fields that would help the government attain its Millennium Development Goals. The allocation was initially Tk 60 lakh for an officer who would like to pursue higher studies. The third revised budget revised the ceiling to Tk 383.82 lakh per officer per degree. Seventy percent of the fund has been earmarked for BCS officers, and 30 percent for project-related officials.

An MA here in a public university is virtually free or heavily subsidised. At a topmost private university, such a degree for 12-18 months should not cost more than two to three lakh Taka. Of course, I am not going to say that a North American or UK degree of the world's top 300 universities is equivalent to ours. However, in most prestigious postgraduate programmes, there are adequate research and teaching funds for which MA students can apply. If an officer has academic interest and the competency for higher studies, they can apply for a fund at any university of their choice. Why pay over three crore Taka of taxpayers' money for the degree of an individual? With what projected outcome? To increase their negotiation skills and bargaining skills as laid out by the project proposal? To make them better policy makers? Needless to say, the policy paper too came from international consultants who have made sure that our money is spent abroad.

We frequently scoff our students for paying negligible fees at a public university, for having their tea and snacks at a subsidised rate. If we really want to make a difference, we need to invest in our rickety higher education system. Follow the Bhutan model where they give merit-based scholarships to university students for studying abroad, making sure that they return to the home country as human capital. If the government really wants to attain the Millennium Development Goals, spend on research and development. Invest that three crore Taka to create laboratories or libraries in each university. Invest in creating better teachers. Instead of one student, you will have many students applying for the public service examinations. Water the roots, not the shoots. By the time these officers are doing their degrees, they are already mid-level in their career paths. With 10 to 15 years left in their services, the overseas degrees will simply enrich the portfolios of these officers and assist their post-retirement plans. The nation is unlikely to get any real benefit out of it. Whereas with such amounts of money, the government could have easily asked local universities to bring in contractual adjunct professors from top universities to run workshops, summer courses, master classes or degree programmes which will benefit not one, but many.

I give the example of the self-catering project of bureaucracy to map its emerging tentacles. There is a syndicate out there that is creeping into our syndicates.

Shamsad Mortuza is Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB), and a professor of English at Dhaka University (on leave).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments