Politicians and misguided economic policy

Economists are taking quite a beating these days. Politicians, most of who feel they understand economics, have either maligned economics or claim they deliver better economics than professional economists! To give some examples, economists have taken the flak from British Brexit Minister David Davis for erroneous forecasts on the impact of Brexit. Davis not only expressed his distrust of the statistics that economists sometimes come up with, but also blamed them for the financial crisis of 2008 and mocked their inability to forecast it. Recently, the entire profession was dragged down in mud for not raising its voice against politicians who threatened to unleash a "trade war".

Economists' woes have been compounded by well-meaning politicians running for elections. Since the time when Clinton won the presidential election by betting on his slogan, "It's the economy, stupid", politicians everywhere have taken a crash course in economics and embraced the language of economists. Voters like nothing better than politicians who can talk economics glibly. Unfortunately, elections and economics have turned out to be a toxic mix. Candidates seeking votes can get away with any promise or "guarantee" as long as they can convince the voters that their election manifesto is based on good economics.

The latest flap occurred when economists joined in a chorus to paint a very rosy picture of the world economy as the year 2017 drew to a close. Last year, for a number of reasons, was a good year for global economic growth. And so, the forecast for 2018 was very optimistic and everybody jumped on the "the future is bright" bandwagon. Even only three months ago, on January 9, the World Bank predicted a 3.1 GDP growth for the global economy. Under the banner, "Global Economy to Edge Up to 3.1 Percent in 2018," the WB waxed eloquent in its opening para of the report: "The World Bank forecasts global economic growth to edge up to 3.1 percent in 2018 after a much stronger-than-expected 2017, as the recovery in investment, manufacturing, and trade continues, and as commodity-exporting developing economies benefit from firming commodity prices." This was before US President Trump initiated his tough talk on imposing tariffs on US imports, and other countries started to push back. Nowadays, the mood has already soured and the tone has changed considerably. Just before government officials gathered for the IMF and World Bank meetings in Washington, The New York Times pointed out that worries about trade and debt are on the rise, and asked, "If the World Economy Is Looking So Great, Why Are Global Policymakers So Gloomy?" Did the economists get it all wrong?

There are many in my profession who take the easy route and blame political leaders for spoiling the party or chastise the media for ignoring the nuances of economic forecasts and the "ifs and buts" inherent in any economic modelling. Any conscientious economist, if asked about the economic impact of a budget deficit, would characteristically prevaricate. A typical response from a seasoned economist would be, "There is no simple answer to whether a budget deficit is helpful or harmful because it depends on quite a few factors." However, all US presidents in the past have promised tax cuts, larger budget deficits, and an economic boom in their election manifesto!

Most of the 2018 GDP growth forecasts made six months ago were based on existing conditions and the absence of any wars, either in the Korean Peninsula or in the global trade frontier! Who knew that President Trump would use tariffs to fix the US balance of trade deficit? Here is a lesson for all prognosticators: Why can't everybody, including journalists, web gurus, and even economists be clear about the uncertainties inherent in economic forecasts? Without being too technical, I always remind my readers that all economic models are based on one key premise: "if everything remains the same". To take a simple case, if taxes go down, the economy gets a boost, that's what economic theory says. But very few pay attention to the clause, "if the extra money is spent on domestic goods." If people hoard their extra cash under the mattress or buy foreign goods, there is zero boost for domestic industries.

Since he took over the helm as POTUS (short for President of the United States, his Twitter account), President Trump has undertaken many actions, in the economic as well as diplomatic front, based on his own knowledge, or interpretation, of economics. The most far-reaching misunderstanding influencing Trump's mind is his belief that trade deficits are bad for the USA, thus equating trade deficit to the debt accumulated by an individual or a business. But, his worldview and his policy actions are guided by what might be called "fake economics" or popular interpretation of economic principles. Like the characters in the movie "Hirok Rajar Deshe" by Satyajit Ray, it appears that many of his cabinet ministers, economic advisers, and his court go along with the wishes of the President. The Commerce Department, run by Wilbur Ross who is leading the charge against free trade, in 2014 figured out that every USD 1 billion in US exports supported about 6,000 manufacturing jobs. Using that rough estimate, some of his advisors claim that the US deficit in 2016, which was USD 500 billion, displaced more than 3 million jobs. And amazingly, these views prevailed, and informed the recent round of tariffs. Economists are now belatedly vociferously defending free trade. Anne Krueger, a former Chief Economist at the World Bank, wrote succinctly in a column for this newspaper, "The Trump administration's stated objective in pursuing protectionist policies is to reduce the US trade deficit. But a current-account deficit (the trade deficit plus the services balance) reflects the difference between saving and investment. Thus, reducing it would require macroeconomic policies to reduce domestic expenditures and increase domestic savings. Protectionism won't help with that!" (April 18, 2018). Alas, some might say, "It's too late, since the boat has already left the port!"

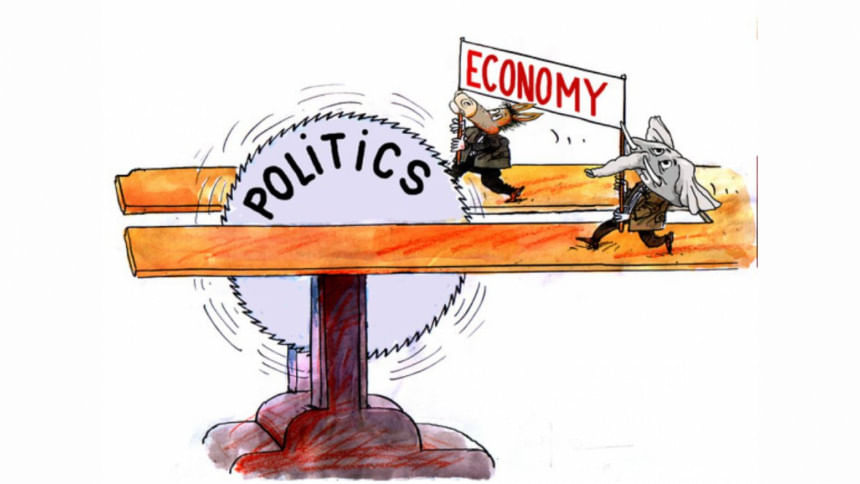

There is another issue, and government economists have to take the blame for not speaking with one voice and were fighting each other to get the attention of the boss in the White House. During the recent debate on US trade policy and negotiations preceding the tax reform legislation in Congress, conflicting views of the effect of tariffs and tax cuts created an environment where the public as well as the elected officials were thoroughly confused. Eventually, the narrative that appealed to the electorate and get the votes in the 2018 mid-term election prevailed. Economists who did not gain the ears of POTUS and lost the battle, could only resign. Or grumble in newspaper columns. Professor Alan Blinder of Princeton University, and former Vice-Chairman of the Federal Reserve, wrote a column in The Boston Globe entitled, "Why economists like free trade but politicians don't," where he sarcastically remarked, "The Lamppost Theory dominates economic policy-making: Politicians use economics the way a drunk uses a lamppost—for support, not for illumination."

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist, and Senior Research Fellow, International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI), a think-tank in Boston, USA. His new book Economic Crosscurrents will be published later this year.

Comments