Are the Rohingyas doomed to a half life?

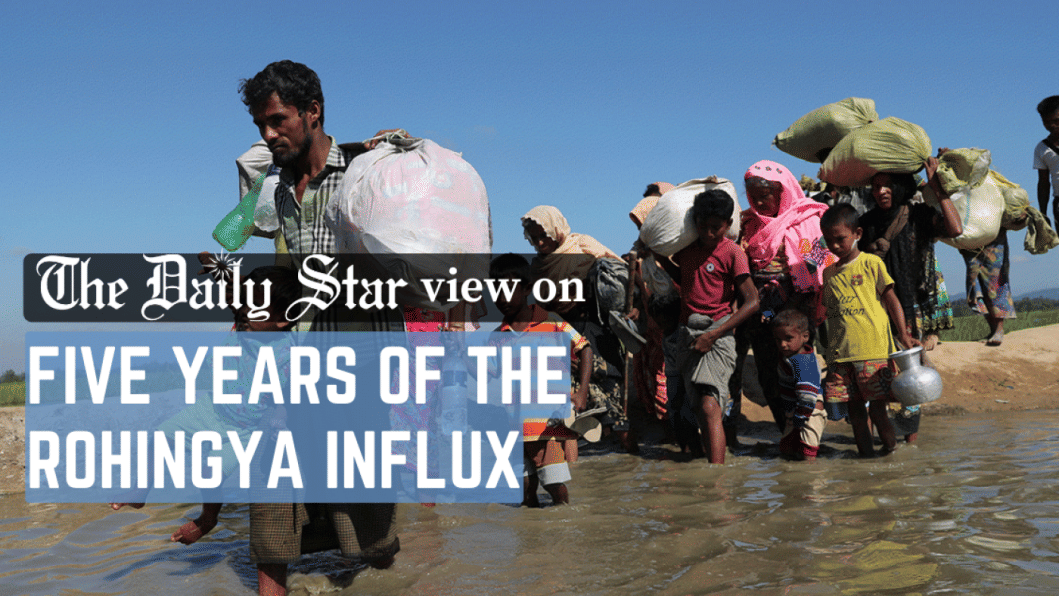

Five years have passed since the Rohingya influx, when around hundreds of thousands of refugees crossed over to Bangladesh fleeing a violent military crackdown in Myanmar's Rakhine state. Despite myriad challenges, Bangladesh has sheltered them since 2017 on humanitarian grounds and provided them with all the basic facilities they need to live in the refugee camps, with the assistance of international donors. Bangladesh signed a repatriation agreement with Myanmar in November 2017, and since then, made two attempts to repatriate the forcibly displaced Rohingyas without any success.

It was obvious from the failed repatriation attempts that the Myanmar authorities were unwilling to take back their citizens against whom they committed a genocide. Although Bangladesh urged the international community to put pressure on Myanmar to create a conducive environment for the Rohingyas' safe and dignified return, we are yet to see any visible development. The facts remain that Rohingyas want to go back to their homeland – provided that they are given citizenship and their safety and security are ensured – and that it is becoming increasingly difficult for Bangladesh to host them.

Although there were enough funds coming in from donor countries in the first three years, funding started to decrease as the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in 2020. And as time passed, global attention moved away from the Rohingya issue to other crises, the latest being the Russia-Ukraine war. But this much is clear: Bangladesh cannot continue to give the Rohingyas proper shelter unless we get enough support from the international community in this regard.

Meanwhile, the situation in and around the camp areas in Cox's Bazar has also deteriorated. Crimes have increased, free movement of the refugees has been curtailed, and education of Rohingya children has been stopped. But if the refugees are deprived of education and livelihood opportunities, how can we expect them to not engage in criminal activities? Realistically, what is a whole generation of frustrated Rohingya youth to do, except languish in the camps, leading a half life, with no foreseeable change in their circumstances?

While the government needs to address these issues to provide the Rohingyas with a better life while they are in Bangladesh, it must also engage in talks with Myanmar authorities so they fulfil all the conditions for the Rohingyas' safe return – such as safety, guarantee of citizenship, freedom of movement, and sending them to their ancestral homes, not to internally displaced persons (IDP) camps.

Since Myanmar is currently facing pressure because of the verdict of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) that it can pursue the Gambia's genocide case, and after the US' declaration of the violence against Rohingyas as genocide, now is the time for the international community to come forward and put further pressure on Myanmar for the Rohingyas' safe and dignified return to their motherland.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments