Can police investigate police crimes with impartiality?

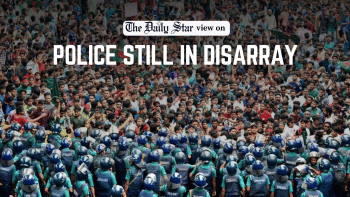

There is no denying the importance of reforms in police force to prevent a repeat of police excesses witnessed during the 15-year rule of Awami League, particularly in its final days when cops indiscriminately shot anti-government protesters, killing hundreds and leaving many more with life-altering injuries. But how to bring about change? It helps that there is a consensus across the political spectrum on the need for reforms. The Police Headquarters (PHQ) also seems to be on board, and the 44 reform proposals it has submitted to the home ministry address some major concerns. But one key area that it has overlooked is the question of transparency in accountability mechanisms if the police are allowed to conduct investigations against their own members.

The PHQ, as per a report in this daily, wants the power to investigate complaints against all officers regardless of their rank. Currently, the home ministry, with assistance from PHQ, investigates complaints when an accused officer is of the rank of ASP or higher. If he or she is an inspector or of a lower rank, the PHQ can conduct the investigation. Unfortunately, both variations of internal investigations have consistently failed to deliver justice throughout the Awami League period, especially in cases of custodial deaths and use of excessive force. How can we trust in this process again? Can colleagues investigate colleagues with absolute impartiality? This may work in an environment free from political influence and internal bias—something we can ill-afford to rely upon given past experience.

Ensuring that complaints against police members are investigated impartially is crucial to upholding justice and establishing public trust. If police or even home ministry officials conduct the investigation, it risks compromising the process. This is why independent oversight is crucial. We support the call for establishing a high-powered, independent oversight body to investigate police crimes, similar to those in countries like the United Kingdom or Sri Lanka, which can help establish accountability in the force. That said, many other things also need to change to ensure its success, including depoliticising decisions related to recruitments, promotions, postings, and punishments. Police performance also needs to be evaluated regularly and objectively to ensure they only serve the public, and serve better.

Some of the reform proposals forwarded by the PHQ do deserve consideration, such as formulating a proper policy on arrests, detention, searches, and seizures by police; incentivising honesty and competence; amending outdated laws; preventing sexual harassment and gender discrimination against female officers; providing proper training on human rights, crime investigations, etc; enhancing logistics to combat transnational and organised crimes; and introducing eight-hour workdays, overtime pay, risk allowances, etc. Currently, the police are still reeling from the disruptive consequences of regime change, but we must not wait any longer to initiate long-term reforms to build a modern, competent, and accountable police force.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments