A lesson on how not to plan govt projects

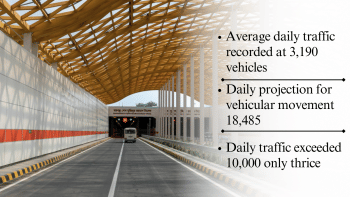

The fate of the much-hyped Karnaphuli Tunnel should serve as a lesson in how not to plan a mega project. As reported by this daily, the tunnel has only seen a third of its projected traffic since it opened on October 28, 2023, with earnings falling short of even the maintenance costs. As of October 20, 2024, the average daily traffic through the tunnel was 3,910 vehicles. In contrast, a project forecast report from January 2023 estimated that an average of 18,485 vehicles would be using it daily. Furthermore, when the government approved the tunnel project in November 2015, it was projected that average daily traffic would reach 28,305 vehicles by 2025 and 37,946 by 2030. Yet, to date, daily traffic through the tunnel has exceeded 10,000 vehicles on only three out of the 359 days since it opened.

In 2015, the ECNEC approved the tunnel project at a cost of Tk 6,446.64 crore. Later, the cost rose to Tk 10,689.42 crore. Of this amount, the Exim Bank of China committed Tk 5,913.19 crore at an interest rate of 2 percent and a service charge of 0.20 percent, while the Bangladesh government—meaning the public—funded the rest. The government is currently paying the interest on the loan from China, but payments on the principal amount will begin within this fiscal year.

The tunnel has thus become a perfect example of the poor planning and forecasting related to mega projects that became emblematic of the former Awami League government. In fact, the projections for the tunnel were so inaccurate that it has managed to earn only Tk 37.45 crore from 14.12 lakh vehicles since its inauguration, while the government has spent Tk 134.46 crore solely on its operation. And this is even before loan repayments start, when spending on the tunnel is expected to significantly increase.

According to the project's deputy director, the planned government and private development projects on either side of the tunnel have not been implemented. Its initial design was based on the vision of "one city, two towns," similar to Shanghai in China. Part of that strategy was to connect the Mirsarai Economic Zone with Matarbari Deep Sea Port and to expand the Chattogram port jetty, as well as to establish thousands of local and foreign industrial units in Anwara. But none of that materialised. With that being the case, on what basis was the tunnel constructed then?

Clearly, it was more of a prestige project for the previous regime that did not care about the various issues that should have been addressed to make it worthwhile for the public. Given the awkward position this places the current government in, we urge it to involve experts and other stakeholders to find ways to mitigate the project's losses, including by developing plans for the region that could eventually make it profitable.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments