One-stop crisis centres must better serve victims

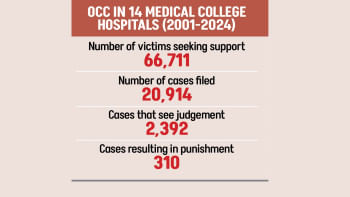

A report in this daily has highlighted a major problem in our legal system—female victims of violence have struggled to get justice for decades, even after seeking assistance at one-stop crisis centres (OCC). The conviction rate of perpetrators is less than two percent. Since 2001, 66,771 victims have sought support at the OCC, according to the report. Among them, 20,914 cases were filed, but only 310 resulted in punishment.

The media has reported over the years on the appalling number of horrific attacks on women and children, resulting in grievous injuries and trauma that can sometimes be lifelong. It is disappointing that, despite having several one-stop crisis centres in various medical colleges, the legal system continues to fail these victims.

Several factors contribute to this failure. Victims who appear in court for say, sexual violence, often face humiliation, which increases their mental trauma and can discourage many from taking legal measures. Cases can drag on for years, with mounting legal costs and social pressures posing additional obstacles to justice. The cost of bringing witnesses for each appearance is another challenge. In many cases, perpetrators threaten the victims or use influence and money to evade legal consequences. Despite the fact that the concerned law stipulates that the trial is completed within 180 days, lack of witnesses and out-of-court settlements results in very low conviction rates.

While one-stop crisis centres are crucial for victims to receive initial medical examinations (for evidence) and treatment, they are not adequately serving the victims when it comes to legal solutions. These centres are meant to provide comprehensive support, however, according to a Prothom Alo report, the conviction rates of cases handled at OCCs are lower than those processed under the Women and Children Repression Act of 2000. The government must ensure that all centres have designated lawyers to provide legal counsel to victims and offer the same standard of support services. In addition to psychological counselling, victims should have the option of going to a safe shelter after being discharged from the hospital.

The reform committee formed under the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs to analyse the challenges and improve conviction rates must address these basic issues. We hope that this ministry under the new interim government will prioritise the efficiency of these OCCs and ensure that victims get the best possible medical support and can rely on a legal system that will ensure that they get justice.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments