Why is government support for poor going to non-poor?

There can be no debate that, in the worst economic crisis that Bangladesh and its people have faced in over a decade, an ever-increasing number of poor and vulnerable groups are in dire need of targeted assistance from the government. It was our expectation that the proposed budget for fiscal year 2023-24 would prioritise their sufferings and dedicate more money than was done in the past towards expanding and strengthening social safety nets. On paper, the proposed budget appears to have done just that – social safety nets, according to the government, constitute 2.52 percent of the GDP in the new budget. However, a closer look at the numbers reveals a distressing scenario, with a meagre 1.01 percent of GDP being allocated towards those most in need.

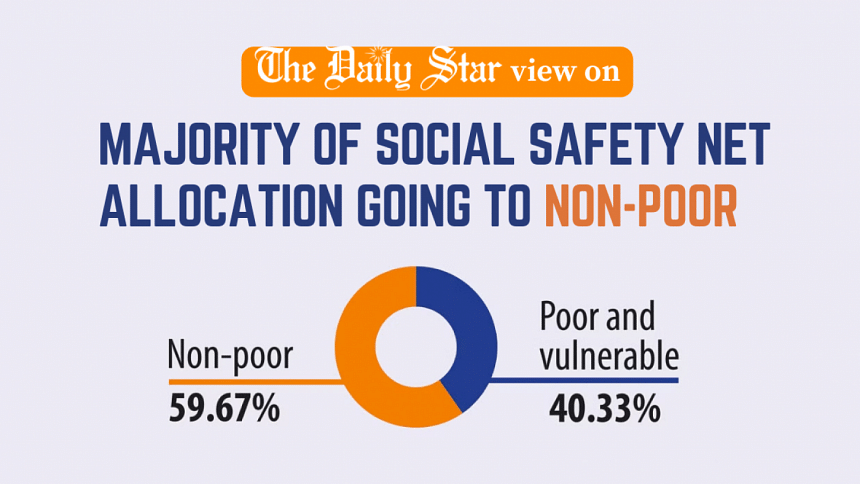

Where is the rest of the money that is being peddled as social safety nets by the government actually going? A whopping 22 percent of the sum will be spent in paying pensions for 800,000 government employees, while another 8.9 percent will finance interest for national savings certificates. Meanwhile, 17 percent of the social safety net budget is going towards agriculture subsidy and interest subsidy for loans to small and medium enterprises, including cottage industries. About 60 percent of the total social safety net allocation proposed in the budget is actually set for the non-poor. The obvious question is why the finance ministry would categorise pensions, subsidies and interest payments under social safety nets, unless it is to deliberately misguide people by flaunting a flashy and inflated figure. The next and equally urgent question is why the poor have once again been left out of the government's planning when they should have clearly been a priority.

Income inequality has risen at an alarming rate, even if we go by the government's own estimate, over the past decade. As our policymakers continue to pander to their already well-off interest groups, more and more low-income households are at risk of falling into poverty, with food and non-food prices long having spiralled out of control. It is shameful that instead of expanding the scope of the social safety net programmes, enhancing their efficacy, and introducing more targeted interventions for new and urban poor, the policymakers have chosen the questionable route of inflating the numbers. In the process, they have made a mockery of those most in need of its protection.

We urge the government to allocate the amount it claims to have dedicated to social safety nets to the actual vulnerable groups. Otherwise, it is tantamount to robbing the poor of their dues from the state.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments