Churchill and India Manipulation or Betrayal?

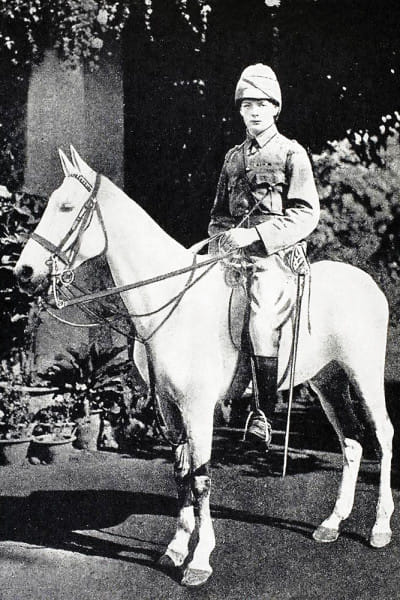

Churchill in India, 1896-99

Winston Churchill spent three years in British India, a freshly minted cavalry subaltern, 1896-99. His attitude to Indians was initially benign, but later morphed into a profound, corrosive hostility. After 1921, he attacked the National Independence Movement, Hindus, the Upper Castes, and to a venomous degree Gandhi, as the cause and personification of India's ills. My book is the first full-length study of that major dark spot in a great life. Amidst 2000+ biographies and Churchillian life-accounts, it is the first holistic study of that connection.

Young officers in British cavalry regiments immersed themselves in army drill, sporting activities like polo, and lead the good life. Churchill followed suit, not bothering to cultivate any of the old British 'India hands'; he wrote to his mother that he met no one that could tell him about the country. It produced self-isolation.

As a Lieutenant in the 4th Hussars, Churchill developed friendships with Indian princes, the game's Indian patrons, profiting from his aristocratic lineage. His father, Lord Randolph, second son of the Duke of Marlborough had made a well-remembered 7-month 'Grand Tour' in 1884-85, before his appointment as Secretary of State for India.

Shaping a political career

What distinguished Churchill from his carefree cohort was his passion at gaining knowledge, and planning for the future. His parents did not send him to university. Pursuing self-education, he implored his mother for books, the classics like Gibbon, Macaulay, Burke, plus the books recommended by his father, reflecting the values of the late-Victorian era. His readings were eclectic, also covering Keats, Kipling, Milton and Tennyson, besides American authors. That engaged him for several hours each afternoon, and during his long rail travels in pursuit of polo tournaments.

Churchill pondered deeply on his future political career. This had three outcomes. One: He absorbed the speeches and life philosophy of Lord Randolph. That vision of India and the Empire is best summed up in Randolph's 'sheet of oil on the surging seas' speech of 1885, on his return from India, in which he compared Britain's management of chaos and dissensions of India, as laying down a sheet of oil to quell that 'vast sea of humanity'. Churchill kept coming back to that analogy during his key India speeches, decades later. [The ineptness of that analogy is different issue]. Two: Churchill absorbed much of what he studied, and thanks to a prodigious memory, decades later, he recalled verbatim large segments of those texts. Three: Churchill understood nothing of India, having not read a single work on the subcontinent's syncretic, varied culture, heritage or philosophy.

Churchill assiduously pursued military adventure, convinced that battle honors would gild his public image, providing a platform for his political career. Britain's Indian Army establishment (controlling both British and Indian troops) abhorred 'medal-seekers', especially those in the guise of 'war correspondents'. Despite Churchill's conspicuous bravery during bloody clashes at the Afghan frontier in 1897, plus his brigade commandant's recommendations, honours were disallowed, besides a minor award.

But war service had an unexpected outcome. In 1898, Churchill transformed his dispatches written for a British newspaper into a brilliant first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force. That brought fame. His self-managed secondment to Omdurman, Sudan in 1898, with further acts of courage, brought another literary success, The River Wars. Those royalty earnings spurred him to a subsidiary career as an author, which became the source of modest wealth from the outset; the earnings ballooned two decades later.

Churchill's deep reflections covering all he had studied, especially his father's worldview, formed the template of his political career. Its immutable core: the primacy of the Empire, with India as the Crown Jewel. He failed to grasp, and refused to accept reality, especially Britain's economic decline after WWI. For him, self-governance in British India, even at a glacial pace, became abhorrent. And he rejected new information. When in 1929, Viceroy Lord Irwin suggested that he meet some Indians to update himself, he exploded: he was perfectly comfortable in his knowledge of India, unwilling to be confused by 'bloody Indians'.

In 1921, Churchill, by then a 20-year veteran cabinet minister, saw in Gandhiji's first Satyagraha campaign (coinciding with the 5-month visit of the Prince of Wales, future King George V), the seeds of the dangerous phase of India's national movement. That antipathy grew into his 1929 break with his own Tory Party, and a decade of political self-exile. His motive: a solo, futile, campaign against the 1935 Independence of India Act. That gilded a reputation for stubbornness. And when he became Britain's Prime Minister in May 1940, his mishandling of India affairs produced major tragedy in those final years of British rule. As Prime Minister, he squandered three valuable years to prepare for Partition (see below). That was betrayal, of both the basic norms of governance and of human values.

Churchill and Jinnah

Churchill's India sojourn included a chance event that produced long shadows. Directly after the 1897 Malakand battles, his brigade commander sent him on a few weeks' attachment to the Indian 31st Punjab Regiment, largely composed of Muslims. That first and only exposure to Indian troops, seared in his mind respect for Indian Muslims. In the 1930-40s that morphed into a relationship, a political partnership with Mohamad Ali Jinnah. This became a vital political choice for Churchill; in February 1940, before becoming PM, he told the Cabinet that India's Hindu-Muslim dispute was 'the bulwark of British rule'. It is not far-fetched to conclude that he fanned those flames.

Jinnah installed himself in London from December 1931 till the end of 1934, as a debonaire, astute lawyer, chauffeured around in a Bentley, clad in Saville Row suits (he collected around 70!). Jinnah explained to close followers that he chose voluntary exile, as the scene of 'political action' had shifted to the UK. He tried to get into the British Parliament, via by-elections, but failed.

Most documents pertaining to the Churchill-Jinnah relationship are lost, perhaps willfully destroyed. At the British National Archives, I chanced upon a letter that Jinnah wrote to Churchill on 2 January 1941. It was not in the papers that Winston Churchill transferred to Churchill Archives at Cambridge in the 1960s. With that letter, Jinnah forwarded to Churchill an interview he had given to a visiting British Labour MP, promoting his own credentials

as the only legitimate spokesman of Indian Muslims. Jinnah wrote: 'Of the 90 million of Mussalmans in this country I speak for fully 90% and my following is growing regularly. We are willing to submit to any reasonable test with regard to this assertion of mine.' Jinnah swiftly followed up with a telegram on 8 January 1941, adding for the first time that he was willing to face a 'plebiscite' to prove his claim. Secretary of State Leo Amery acknowledged these two messages with a return telegram.

Roosevelt and India

Churchill sent copies of the above messages from Jinnah to Roosevelt; he also circulated them to the British Cabinet (that's how they survived in the British Archives). That was the only mention of 'plebiscite' in the political dialogue of that time. Of course, Jinnah stretched the truth by a wide margin. Remember, in the 1937 Provincial Elections, the Muslim League had won less than 24% of the community-mandated seats, also failing to win power in any of the 14 provinces.

President Franklin Roosevelt sent a blunt message to Churchill on 11 April 1942, just as Stafford Cripps was leaving India at the termination of his infructuous 'Mission'. FDR wrote: 'The feeling is almost universally held that the deadlock had been caused by the unwillingness of the British Government to concede to the Indians the right of self-government, notwithstanding the willingness of the Indians to entrust technical, military and naval defense control to the competent British authorities. American public opinion cannot understand why, if the British Government is willing to permit component parts of India to secede from the British Empire after the war, it is not willing to permit them to enjoy what is tantamount to self-government during the war.' (emphasis added). Clearly, FDR referred to a secret Churchill plan, dating at least to early 1942, to create a South Asian Muslim homeland. That's new information (Kimball, Churchill and Roosevelt, 1984, Vol. 1, pp. 445-7).

Churchill's reaction is recorded by Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt's personal representative, who was 'embedded' with Churchill for weeks on end, during much of 1942, spending most evenings and half the night in the War Bunkers. Hopkins went to London in early 1942, empowered with a letter of introduction to King George VI. It became one of the most unusual arrangements in diplomatic history, bypassing the US Ambassador in London. Hopkins wrote: FDR's message was greeted by Churchill with a 'string of cuss words lasted for two hours in the middle of the night' (Kimball, 1984). A reply was dictated to a stenographer on the spot, in which Churchill threatened to resign as PM. That draft message was not sent but was given to Hopkins and survives in the Kimball papers. The reply actually sent, used emotional blackmail; 'a serious difference between you and me would break my heart'. The 'draft not sent' became a Churchillian device to speak his mind, off the record, an innovation in summit-level diplomatic communication. After that episode, FDR only raised the India issue in correspondence, and once in direct talks in mid-1943.

Churchill's falsehoods

Author of Churchill and Secret Service (1997), David Stafford notes that Churchill was much ahead of his contemporaries in using intelligence services. India's Intelligence Bureau, from its earliest 1835 incarnation, predates its British counterparts. Perhaps they contributed with a speculative report, producing one of Churchill's biggest fibs of WWII. Churchill told Hopkins on 11 May 1942 that a nationalist government in India would recall Indian troops from the Middle East and give 'free transit' to Japanese troops through India to cross Asia and join up with German troops! (Davis, FDR: The War President, 2000, p. 470). That bizarre story was repeated in Churchill's 13 August 1942 message to FDR (Churchill was outraged when FDR sent him a message from Chiang Kai Shek about release from prison of Gandhi and Nehru). Churchill wrote: 'You could remind Chiang that Gandhi was prepared to negotiate with Japan on the basis of a free passage for Japanese troops through India in the hope of their joining hands with Hitler (Churchill Archives 20/76). This is a nonsense story, in facts, geography and logistics.

Historical studies and archives

When key documents are missing, we are left with scraps of information, which read together make up a partial mosaic that points to hidden truths. My book also offers these and some other bits of evidence that bear reflection. I hope that my holistic survey of Churchill's India connections, the first of this kind, may lead to other, deeper studies, in a shared, determined search of elusive truths. In all such efforts, it is the archival collections and personal papers that are vital to historical analysis.

Kishan S Rana is a former diplomat, teacher and author of Churchill and India: Manipulation or Betrayal? (2023).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments