ICJ ruling on Kulbhushan Jhadav puts Pakistan under pressure

The July 17 judgement of the Hague-based International Court of Justice (ICJ) in a case relating to former Indian Navy officer Kulbhushan Jadhav has seen India coming out a winner on most counts against Pakistan. While any India-Pakistan standoff is almost invariably accompanied by chest-thumping and jingoism, it is time to sift the hype from the reality. The Indian leadership's welcome of the ICJ ruling stood in contrast with the noise of strange bravado put up by Pakistan Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi even after the UN's principal court's sharp rebuke and rejection of almost all contentions of Pakistan. So, it is time to look at some of the incontrovertible messages from the ICJ ruling.

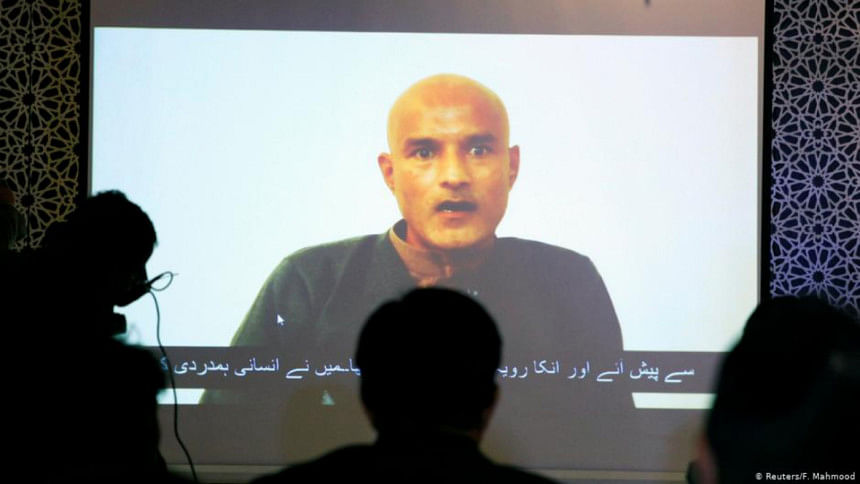

With regard to Jhadav, who was convicted and sentenced to death by a Pakistani military court in a summary trial in April 2017 after being charged with espionage and subversion activities, the ICJ endorsed India's stand that Pakistan was in gross violation of Article 36 of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations by delaying in informing either him, or India, and not granting access to Indian diplomats to him and not allowing him legal representation. The ICJ also suspended Jadhav's capital punishment till the Pakistani military court's verdict is not reviewed and reconsidered with all the trappings of a fair and transparent trial. The ICJ asked Pakistan not just to give Jadhav his legal rights but also allow consular access to him by India because of Islamabad's actions mitigating against the Vienna Convention and the cannons of a fair trial.

India, for which the pressing need to move the ICJ in 2017 was to save Jadhav from execution and expose Pakistan's violation of international law, had also urged the ICJ to order Pakistan to free Jadhav and facilitate his return home. True, this plea was not accepted by the court not because of its merit, but on the ground that its jurisdiction was limited to applying the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. This was seized upon by Qureshi to interpret that the ICJ wanted Jadhav to remain in Pakistan and continue his trial in that country. However, here too Pakistan has more reasons to worry about than to feel smug because the ICJ has outlined the parameters of a fair and transparent trial of Jadhav. It is true the ICJ left it to Pakistan to choose the means of review and reconsideration of the Jadhav case but made it clear that this freedom is unqualified.

As of now, there is no clarity from Pakistan if the Jadhav case would be handled by that country's military or civil judiciary. All that Prime Minister Imran Khan has said in his initial reaction to the ICJ ruling is that Pakistan will go "as per the law." The ICJ in its verdict had unambiguously pointed to the opacity of military courts in Pakistan by noting that it was not clear whether the Pakistan army chief had acted on Jadhav's clemency petition. But more importantly, the ICJ pointed out that "it is not clear whether judicial review of a decision of a military court is available on the ground that there has been a violation of the rights set in Article 36, paragraph one of the Vienna Convention." The ICJ's remarks seem to have raised big question marks about the military court in Pakistan and about possible remedies in civil courts for Jadhav.

The ICJ also pointed to Pakistan's own argument that the country's Constitution has been interpreted by the top court as "limiting the availability of review" jurisdiction by that country's high courts for a person like Jadhav who was subject to Pakistani Army Act. It is precisely in view of the opaque military justice dispensation mechanism in Pakistan, the ICJ had said that the review and reconsideration of Jadhav's case must be "effective and unconditional and must lead to a result." Using Pakistan's own argument, the ICJ went to the extent of advising Pakistan to consider enacting "appropriate legislation" as part of the review process for Jadhav.

The ICJ pointed out in its judgement that "respect for the principles of a fair trial is of cardinal importance in any review and reconsideration" and stressed on the need for guarding against any potential prejudice and implications for evidence and the accused's right to defence during the review of the Jadhav case. Clearly, the ICJ has thrown the ball in Pakistan's court.

So, much depends on what Pakistan does post-ICJ ruling. Will the Jadhav case go back to military court in Pakistan or will it be referred to civil courts in that country? What is the process and facilities of review and reconsideration that will be made available to Jadhav to defend himself? The ICJ has obligated Pakistan to answer these questions. And the search for the answer, if sincerely undertaken by Pakistan, is likely to be a long-drawn process in Pakistan not known for its speed in such cases. However, the most important message of the ICJ ruling is that Jadhav's capital punishment cannot be implemented until his case was reviewed and reconsidered.

Pakistan has used Jadhav as a ploy to counter India's sustained campaign against cross-border terrorism and to tell the international community that India was allegedly behind the unrest in Balochistan. Indian officials feel Pakistan might be tempted to use Jadhav as a diplomatic tool to resume diplomatic engagement with India stalled since long. The assessment in Pakistan is that with Jadhav in their custody, India might be trying hard to seek his return.

The Jadhav case might offer an opportunity for a diplomatic engagement between India and Pakistan. Even if it happens, India needs to sustain its efforts to keep up the heat on Pakistan by pressing on with steps to diplomatically isolate that country. In fact, the ICJ ruling must be viewed as part of those efforts among a string of moves by New Delhi to corner Pakistan in the last couple of years including the designation of Jaish-e-Mohammed chief Masood Azhar as a global terrorist by the UN in May this year, and blacklist Pakistan in the inter-governmental body of Financial Action Task Force dealing with anti-terror financing matters.

A major challenge in ensuring enforcement of the ICJ's rulings is the absence of any mechanism unless the UN Security Council steps in to do so. There are at least five instances when the ICJ rulings have not been complied with. During the Cold War era, the US had done so in 1986 when Communist Nicaragua in central America obtained a favourable judgement against the United States for funding and arming the contra rebels against the then Nicaraguan government. The US had succeeded by moving the Security Council against the ICJ order.

Pallab Bhattacharya is a special correspondent forThe Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments