Spiralling anger and nuclear dangers

In the summer of 1945, a jittery premonition marked the lives of the citizens of Hiroshima, as B-29 super fortresses—planes that the Japanese locals called B-San or Mr.B—had been stationed in the northeast corner of the fan-shaped city. Americans had been bombing Japan for months except in two key cities: Kyoto and Hiroshima. A rumour was lurking around, however, that the Americans were saving something special for Hiroshima. The prefectural government, sensing impending attacks, had ordered completion of wide fire lanes, hoping it would contain fire caused by raids. The depraved radioactivity of the fire to come was something that no one had comprehended.

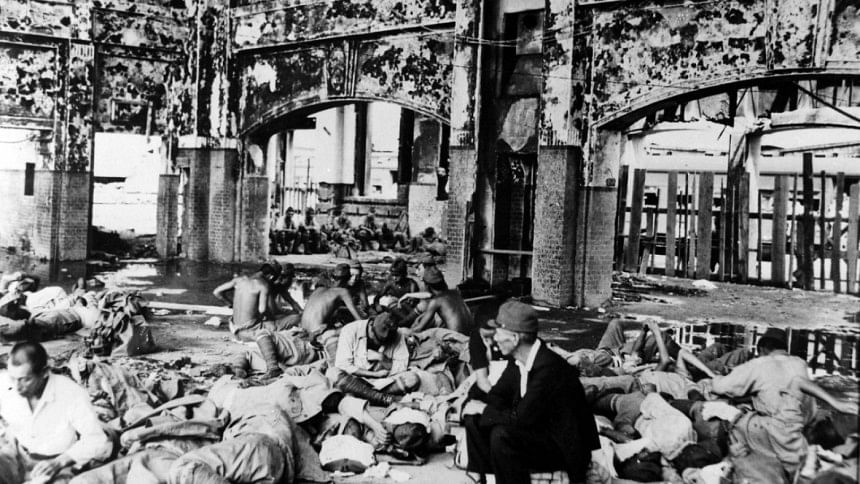

August 6 started out as a tranquil day until at exactly five minutes past eight, a titanic flash of light cut through the sky: the Enola Gay. The rumour now manifested a deafening reality of hell on earth: a lethal "Little Boy" that killed 100,000 people. For Hatsuyo Nakamuro, a Hiroshima resident, the atomic bomb reflected that unlucky split second that buried her children in debris, and somewhere nearby, her mother, brother and sister too. The horrid aftermath unfolding around her reached so far behind human mind that it was impossible to think it was caused by human beings, like the scientists who designed the disaster, the pilot of Enola Gay, or President Truman, or even Japanese militarists who had helped to fill her surviving lungs with the aftermath of radiation, who had brought the spoils of war to her weak and destitute bones.

"The bombing almost seemed a natural disaster—one that it had simply been her bad luck, her fate (which must be accepted), to suffer," wrote the New Yorker journalist John Hersey in his article "Hiroshima: The Aftermath" in July 1985, narrating Nakamuro and other survivors' stories four decades after the nuclear nightmare. Almost 39 years earlier, in August 1946, a year after Japan's surrender, Hersey had published his first coverage of Hiroshima––a 30,000-word account of six survivors. Ominously titled "Hiroshima", it birthed a new kind of journalism—non-fiction story-telling with the elements of fiction—and changed the construction of historical narratives by extrapolating from underneath the cataclysmic mesh of politics and militarisation in war, the simplest yet omniscient cost and witness to it all: human lives.

Today, 74 years after the worst apocalyptic human actions, Hersey's Hiroshima seems more relevant than ever, as possession of nuclear weapons has become a modicum of economic superiority, and global and regional domination.

On February 2, 2019, first the United States and then Russia announced a formal suspension of their obligations to their Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, signed in 1987 by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, which forbade the US and the then Soviet Union from producing, testing or deploying mid-ranged, ground-launched weapons. The exit is to officially take place on Friday, August 10. One of the reasons stated by President Trump included his frustration that China was not involved in the treaty. Arms control advocates have been warning that the termination of the INF along with trade tensions can provoke a nuclear arms race. And that seems to be a very near reality: on August 3, 2019, US Defense Secretary Mark Esper told reporters that the US was considering deploying new missiles in Asia, a move likely to anger their Chinese competitors, which also have been known to conceal and manoeuvre production of ballistic missiles.

There are plenty of other examples of nuclearisation in today's world, painted all across world politics this year, such as the Iran-US relations that teetered on the knife edge of an imminent nuclear war, after the US imposed sanctions on Iran in May 2018. While the turbulence has subdued, it is nowhere near over. Last Wednesday, the US imposed sanctions on Iran's foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, and according to the parliamentary news agency Iceana, Zarif said this Saturday that Iran will take further steps to reduce its compliance with the landmark nuclear deal from 2016. On the other hand, following President Trump's historic visit to North Korea, Wall Street Journal's intelligence analysts concluded that "the secretive state is accelerating its production of long-range missiles and fissile materials, both key components in nuclear weapons."

Despite these ongoing issues between the nuclear states, India and Pakistan—closely backed by the US and China, and with 140 and 150 nuclear weapons that each possesses respectively—are the only two nuclear powers to have "bombed" each other in history, earlier this year in February, after a Kashmiri suicide-bomber, allegedly belonging to the Pakistani-based Jaish-e-Mohammad, killed 40 Indian troops. India's subsequent launch of airstrikes—and as long as the diplomatic negotiations were being eschewed and threats of "all eventualities" were being fired, the threats of the age-old border conflict spiralling towards a flashpoint for a future nuclear war—was certainly real and deadly. The current global situation reflects the proliferation risks of nuclear power, which arguably reconstructs the chances of history repeating itself, in the midst of a regional or international crisis.

That's precisely why revisiting the destructive birth of the nuclear age is crucial. But this commonly means fixating ourselves on the planned Hiroshima attacks, and narratives that stress the overbearing power of science that ended hundreds of thousands of human lives in a matter of minutes. But the massive human cost was rendered boundless and innumerable not only by the atomic chemicals, but the war-numbed heartlessness of those who, three days after Enola Gay wiped out Hiroshima, continued on the second mission of Operation Centerbomb II to bomb the urban and industrialised Japanese city, Kokura. The atomic payload used this time, called Fat Man, was signed by the pit crew who had assembled it, some had even written messages—"Here's to you" and "a second kiss for Hirohito." (Similar distasteful nationalism at the expense of war undergirded people's reactions on social media to the Kashmir turmoil this year.)

For reasons still debated upon by historians, the visual bombing of Kokura couldn't be managed, and in forty-five minutes or so, a secondary target was decided and destroyed: Nagasaki, where nearly twice as many were killed and injured. President Truman himself had been surprised by the second bombing, coming as it did so soon after the mass destruction of the first. The day after Nagasaki, Truman issued his first affirmative command regarding the bomb: no more strikes without his express authorisation, one he failed to give earlier. Even if Hiroshima—as the first devastating planned nuclear attack in human history—remains the most prominent deterrent example, Nagasaki, with greater consequences, saw the first use of a nuclear weapon to wage raw anger. Nations today must ensure it will be the last.

Ramisa Rob is a master's candidate in New York University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments