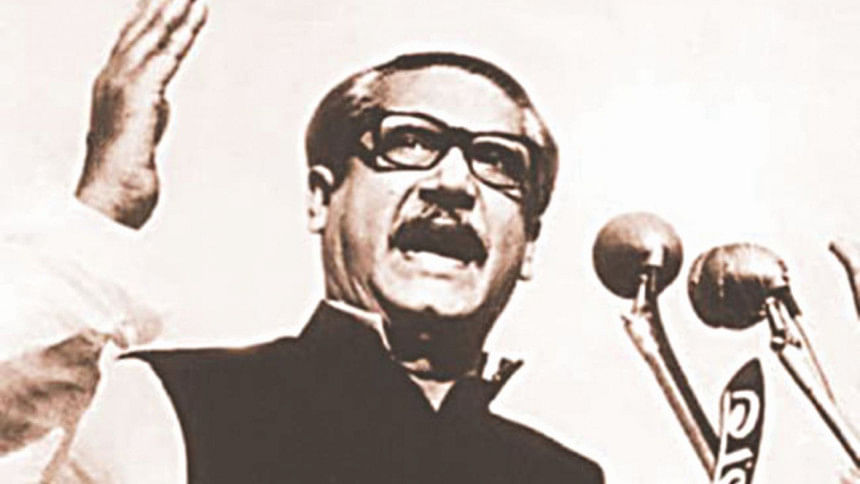

A hero of the past, present and future

After the killing of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Khandaker Mostaque's illegitimate government needed a foothold. He sent envoys to Moscow, London and such places to explain his position. Her Majesty the Queen of England refused to meet his emissary, a senior leader of Awami League. "You have killed your greatest patriot and you have come to meet me! I have nothing to discuss with you!" The Queen spoke words which soothed a million hearts in Bangladesh. Shaheed Quaderi, one of our finest poets, cited the killing of the great leader as one of the major reasons for his migration to Europe and later to the US. In a poem he expressed his great surprise that the killers of Bangabandhu were Bangladeshis. "I shall never hear anything more horrifying." How could Bangladeshis kill Bangabandhu, the man who loved his people to a fault? The man who fought all his life to free his people from colonial rule?

Did the Chileans kill Salvador Allende and replace him with General Pinochet, a military dictator who took his people a hundred years back? Were the great patriots of Africa, Asia and Latin America killed by their own people?

But the final verdict is history's. A great patriot doesn't die, he returns with a thunder. His people keep him alive in their hearts.

It was Friday, August 15, 1975. It was one of the most tragic days of our history. It reminded us of the dark night of March 25, 1971. The Father of the Nation, loved and respected in Bangladesh and the world over as a great hero, lay dead on the stairs of his famous residence at Road Number 32, Dhanmondi Residential Area. He was only fifty-five.

At dawn on August 15, I woke up to hear from my parents that Bangabandhu had been killed along with his family.

Even ten-year-old Sheikh Russell was not spared. My initial reaction was of great shock. I was dumbfounded with sorrow. Bangabandhu didn't deserve a death like this. He was our greatest hero. His love for his country and his people was unparalleled.

Announcements of his death were being made on radio and TV at regular intervals. A certain Major Dalim was claiming credit for his death. Who was he? We had never heard of him before! There was fear, there was confusion. There was a silent sorrow among his followers and people who admired him.

Years later, I learned that the first procession to protest the death of Bangabandhu was organised by the boys and girls of Chhatra Union in my own district of Kishoreganj. They warned the real killers that the death of this great patriot would turn Bengal into Vietnam. Student leader Kazi Abdul Bari led the procession. Chhatra League leaders went into hiding because they were the most wanted people by the Mostaque government. Many were eventually arrested and tortured. We were not political activists but we were young and patriotic. We weren't cowards. A few of us got together and walked up to Bangabandhu's residence, which was less than a mile from our area.

There was army patrol on the roads and police guard in front of Bangabandhu's residence. We heard that tanks were guarding Khandaker Mostaque in Bangabhaban. We were not allowed inside Bangabandhu's residence but nobody disturbed us when we stood silently in front of House Number 32 and paid our respects to the greatest son of the soil. The killing of the entire family (except his two daughters who were living abroad then) was too great a shock for us. We spotted bullet marks on the walls. An uncle of mine, who was a journalist working for BTV, had seen Bangabandhu's dead body the next day. We listened to him in rapt attention when he told us what he saw inside. Before the curfew was clamped again on August 15, we also managed to see Sheikh Moni's residence. There were signs of machine gun fire on the walls. Even women and children were not spared in this house either. Why this mindless killing? To spread fear? To terrorise the people and silence them? Dhaka had suddenly gone back to the Pakistani days, it appeared. Had thirty lakh people embraced martyrdom for nothing? Was our glorious fight for independence meaningless?

The acting chief justice of the Supreme Court, Justice Syed AB Mahmud, had administered the oath to Mostaque. The vice president, ten ministers and six state ministers had also taken oath. There were a few respected names in the cabinet. Were they forced to join Mostaque? The three services chiefs were also present.

Members of parliament charged with corruption by Bangabandhu were present too. Mostaque, it appeared, wanted to tell the world that only Bangabandhu was corrupt and his ministers had no fault. The Pakistan government was quite happy. Bhutto's reaction said it all. Both Bhutto and Kissinger had visited Dhaka a year or so back. Bangladesh Betar had instantly become Radio Bangladesh. What was wrong with the Bangla name? The curfew helped Mostaque take control in less than fifteen hours. People talked about his cunningness. A few secretly called him the new Mir Jafar. He spoke to the nation in the evening. His words couldn't alleviate our fear and anxiety. We were happy to note that the stalwarts of the Mujibnagar government didn't join Mostaque. Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, Captain Mansur Ali and AHM Kamruzzaman didn't betray their leader. Abdus Samad Azad, Zillur Rahman, Abdur Razzak and Tofayel Ahmed didn't join Mostaque either.

That night we went to sleep with a heavy heart. But our love and respect for the martyred Bangabandhu grew even more. He was our greatest hero. He is a hero of the past, present and future.

Junaidul Haque is a novelist and critic and a researcher on Bangladesh's history.

Comments