Gandhi’s sojourn in Noakhali

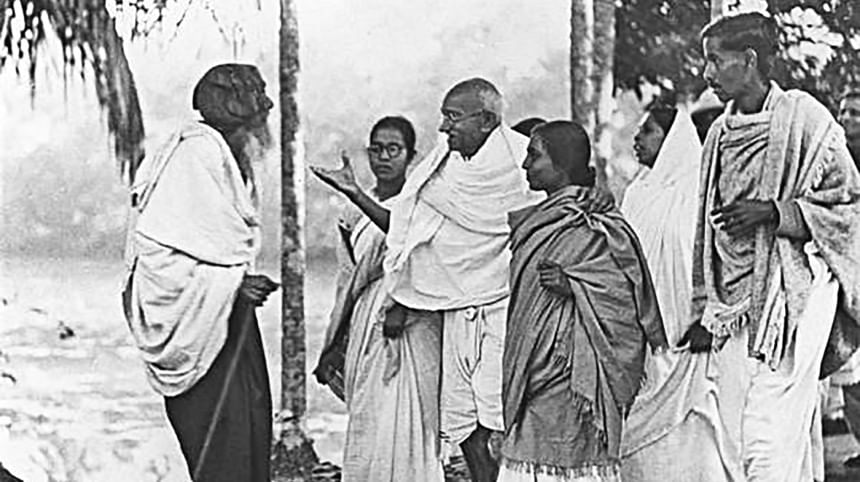

There are many ways a nation's history can be understood, for it has many points, opinions, and arguments depending on the sources one can reach. To comprehend history, scholars have recently started turning to memories in their efforts to make sense of the past. On the occasion of Mahatma Gandhi's birthday on October 2, we can take the opportunity to examine the memories of his visit to Noakhali to remember the "champion of non-violence."

Memories are being used as a tool to reconstruct the past, as much it was imagined as it transpired. This article is aimed at seeing Gandhi's visit through recollection, commemoration, and social manners and mores. It is a repertoire of interests, and collective mentality about the local history of India's partition. Gandhi's Noakhali visit in 1946 was rarely examined directly through collective memory, neglected as just a case study that fails to reveal the long-lasting legacy Gandhi left behind, as can be found in the oral recollections of the villagers in Noakhali.

Gandhi's sojourn in Noakhali sparked many political debates and opinions, alleging him of downplaying the cause of the Muslims, who were victimised by the communal riots in Bihar that erupted immediately after the violence in Noakhali. However, Gandhi intended to heal the communal scars in the Muslim society in Noakhali, aiming to set an example for the rest of India of how Hindus and Muslims can get along. However, while relevant, the focus of this piece is not the political agenda of the time, but rather the local history of Noakhali during Gandhi's visit, and how he was mainly seen from the Muslim perspective and is still remembered in the community by people who had no political affiliations and ambitions.

Hindu-Muslim relationships in Noakhali in late 1930s

Before delving into the memories of Gandhi's visit to Noakhali, let us have an overview of the Hindu-Muslim relationships in the area the decade before. The relationship took a hit when Khitish Babu, a schoolteacher in Lamchar, Noakhali, who happened to be Hindu, called his Class 7 student, who was Muslim, haramjada (bastard). This was an offensive to Muslims, especially coming from someone who was Hindu. Following that, a large meeting was called by Golam Sarwar, the local MLA and a Muslim political leader, in Lamchar on April 12, 1939. Sarwar protested this incident and was agitated about how Hindus dared rebuke a Mohammedan student with this filthy language. He asked for an apology from the school authorities and said he would go on a strike at the school otherwise. He further threatened the teacher by dragging him round the street with shoes around his neck – an unimaginable insult for a teacher.

A Congress leader from the Hindu community at the time, Monoranjan Chowdhury, wrote a letter to Gandhi regarding this communal propaganda spread by Sarwar, and requested him to take immediate steps. He was angry that Hindus in Noakhali were switching from Congress to Hindu Mahasabha. What wasn't mentioned in the letter was that the Congress leader had also made references and an allegation of Bengal Muslim leaders failing to check the communal tensions, which was featured in the local newspaper. One particular point the newspaper addressed was about Sandwip, Noakhali, where, for 12 years, an agreement was in place between the two communities. This agreement stated that Hindu processions could pass in front of mosques, playing music, except during prayer hours. In 1939, on the Bijaya Dashami Day, the local Hindus employed the agreement. But the sub-deputy collector and circle officer-in-charge wrote to Babu Rajendralal Nag, BL on October 21, 1939, "I consider it my duty to let you know and you are probably aware that a civil tumult may arise if music is played near the mosque at any hour on the Dashera Day."

"There was a time when Indian Musselman used to listen to me, but now (they) regard me as their enemy number one. I worked with the Ali brothers, Azmal Khan, and many others for years. I tell you; I am not an enemy of anybody on Earth. I am a servant of God, i.e. truth."

There was an allegation about Krishak Samitis as well. Hindu leaders demanded for the appointment of a committee of inquiry to look into the cases of communal tensions and violence. In response, the then Home Minister Sir Nazimuddin insinuated that there was no precedent condition to such inquiry. He said all the issues they lamented about were false, baseless, and malicious – an attempt was made to malign this government without any reason whatsoever. He claimed that it was a ploy of Hindu zamindars and mahajans, whose illegal exactions had been checked by the Krishak Samitis of the district. No immediate response from Gandhi was found in 1939 concerning the problem, making it more difficult to assume whether he took time to go over the letters sent from Noakhali. However, he responded by visiting the district in 1946, indicating that he was aware of the situation and the growing differences between the two groups. To bring the community together during the riots and before partition, Gandhi travelled to Noakhali with his "peace mission," an idea that can be used interchangeably with non-violence.

Remembering Gandhi

Memories endure only within the social context that they were created in, with communities largely defining the conceptual structures that individuals use to recall information. The socially acquired understanding of the past is a patchwork of personal reminiscences constructed and pieced together within this social dimension (Hayden White: 1987). Thus, the relationship between memory and an understanding of history through social context is one of mutual influence, both parts greatly effecting and relying upon the other. Regarding the individual memories of Gandhi, I took oral interviews in the places Gandhi visited in 1946. The attempt was to retrieve individual perspectives on Gandhi, which coalesced into an image. One of the people that I interviewed, Motalleb Patwary, who is now 88 years old with a round wrinkled face and a goatee, shared, "There were no places left untouched by the rioters in Chandpur. While the whole place was aflame, there were no human casualties. Immediately after the riots, the Gurkha Army first came to our area. Then, Gandhi arrived with his two granddaughters, and his message was calming and noble. Gandhi spoke to the mass people in a comforting tone. Nothing was out of order. He tried to make the communities understand that we, Hindus and Muslims, were brothers. There was no point of fighting each other. We were trying to drive out the British rulers; while they were leaving, they made us fight one another." Patwary and his maternal cousin joined Gandhi's prayer meetings. He also added that there was no one in the village who did not attend the meetings; everyone, young and old, was there.

As the interview went on, Patwary also mentioned, "Everyone was waiting for him to come. There was a whole sea of people." Despite the issue of riots which was what Gandhi was trying to address, Gandhi the individual became a hot topic in the community. Because of the poor communication system back then, the roads Gandhi travelled were renovated by filling ditches, and bridges were made where needed. An air of festivity had settled in the area. The news of his visit led to the resolution of a lot of issues. People who were forcefully converted to Islam became Hindu again. More importantly, the perpetrators of the riots went into hiding, while many of them went to apologise to the Hindus. Patwary's experience resonates with Tofael Ahamad, who was, then, a student at Chatkhil Panchgaon Government High School. He wrote in his book, "'Let's go see Gandhi,'saying this, we ran" [Mahatma Gandhi in Bangladesh (East Bengal), Dhaka: Panchgaon Prokashoni, 1992, P. 1-5]. He further described that it was not more than a quarter of a mile from his house where Gandhi came – a 10-minute walking distance. His aura was powerful, and it seemed like Ahmad needed to see him and attend his meeting. Even though he didn't like who Gandhi was and why he came, he still felt an urge to see him.

Gandhi's sojourn in Noakhali sparked many political debates and opinions, alleging him of downplaying the cause of the Muslims, who were victimised by the communal riots in Bihar that erupted immediately after the violence in Noakhali. However, Gandhi intended to heal the communal scars in the Muslim society in Noakhali.

Noni Bala Bonik was protected by her Muslim neighbours. She was 90 at the time of the interview, but had sharp and detailed memories on Gandhi. She recalled, "Gandhi came like a messenger and set up some temporary camps. I attended his prayer meetings twice and received chocolates." For Noni Bala and other Hindus, Gandhi appeared like a saviour after the riots, as everyone assumed that since he was around, nobody would have the courage to unleash violence again. After Gandhi's assassination, Noni Bala and her family members lived in anxiety for days fearing that riots may break out again. But nothing happened.

Whatever the Hindu or Muslim positions were in Noakhali seven decades ago, Gandhi was able to bring the community together. Sumit Sarkar defined it as Gandh's "finest hour." The principal of Chaumani College, Tafazzal Husain, equated Gandhi with a prophet. Gandhi wrote a letter to Husain and shared his emotion. "There was a time when Indian Musselman used to listen to me, but now (they) regard me as their enemy number one. I worked with the Ali brothers, Azmal Khan, and many others for years. I tell you; I am not an enemy of anybody on Earth. I am a servant of God, i.e. truth. I shall stick to this job till I die, or someone kills me (Smritikana (Bits of Memory) (Dhaka: 1978), P. 83)" His statement revealed the internal conflict he had been going through before the partition. He wanted to return to Noakhali after the partition and spend the rest of his life with the Muslim community. More importantly, he compared riots with cancer, which needed to heal before it spread to the whole body of Indian polity. He said prevention was better than cure. Noakhali gave him the opportunity to set an example of communal harmony for the entire Indian subcontinent.

Gandhi's monument

The Gandhi Ashram Trust, a philanthropic organisation in Noakhali, built a monument to convey Mahatma Gandhi's legacy and memories to the next generation. One can see the 20-foot, white stone sculpture of Gandhi standing upon a plinth and welcoming visitors. He is shown holding a walking stick in one hand, his other hand gently at his side. The statue is surrounded by a gorgeous garden of all sorts of trees and foliage. The image is simple and inviting, while still conveying the power of Gandhi's presence. It was built to commemorate Gandhi and the history of riots in Noakhali. This monument connects us to the history and power of resistance to violence as well as a willingness to reject riots. It always sparks a conversation among people and a broader public image which unites the community.

A monument is the embodiment of memories, a place bridging different generations. It helps us rethink the past that it perpetuates. Moreover, it is a constant dialogue between past and present, based upon which we can make decisions for the future. Gandhi's monument in Noakhali reveals the past to which we belong and how to learn from it. It also speaks to the community's crisis, trauma, and grief. Gandhi's legacy will continue in Noakhali through his monument, and let people understand the flag of peace he sailed with on his journey throughout Noakhali.

Parvez Rahaman is a PhD candidate at Middle Tennessee State University in the US. Email: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments