Teachers aren’t under siege, but justice, civility and reason are

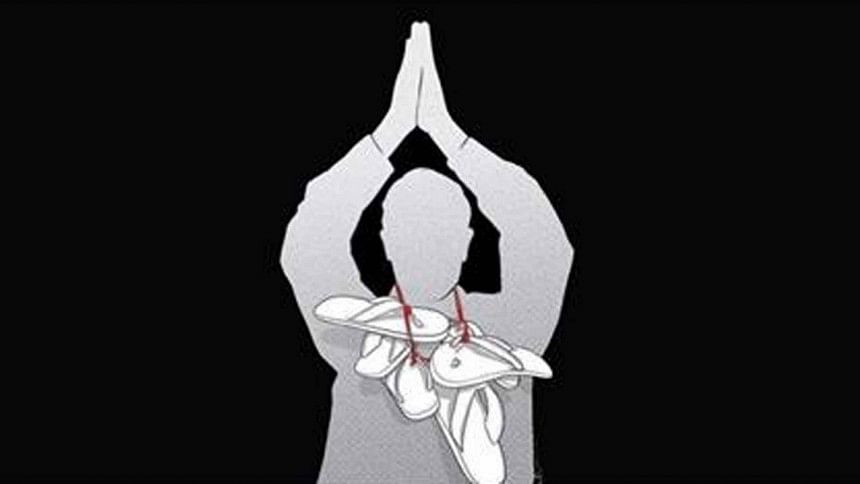

Here's an image that will likely be seared into our memory for long: a teacher being forced to wear a garland of shoes around his neck. Watching the grainy video that surfaced on YouTube, you could almost mistake him for a leader as he emerged from a building, flanked by police, with his pressed hands high in the air, as if to greet waiting crowds… except it was not. Except the police there were just dummies. Except the crowds outside gathered to witness his ultimate humiliation.

Moments like this can be strangely evocative. In 2008, when an Iraqi journalist threw a shoe in the direction of a US president, it came to represent the pent-up anger of a nation for an unjust war that the US had imposed on it. Pent-up anger was again at work when vindictive crowds in Narail sought to recreate that moment, and it was no coincidence that their target was a Hindu. Regardless of the contrasting symbolism of shoes, enabling heroism in one instance and villainy in another, moments like this, once you see them, are hard to unsee.

What was Swapan Kumar's crime? He tried to save a student, also a Hindu, who wrote a Facebook post in support of Nupur Sharma, a now-suspended leader of India's BJP who had made derogatory comments about Prophet Muhammad. This made ideal fodder for their tormentors whose anger at a faraway enemy was, until that point, restricted to helpless outbursts on social media.

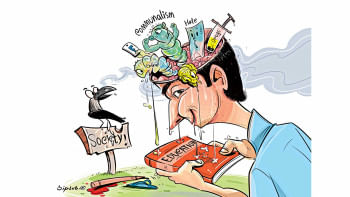

But if we're being honest, many things had to go wrong for a moment this disturbing to be born. Regardless of the communal undertone, it was actually the result of a complex interplay of several factors including the rise of the Muslim Right and shrinking space for diversity, a general anti-India feeling, crumbling of democratic institutions, and moral decadence in a society where long-cherished values – like respect for teachers or elders – are being playfully tossed about. Can we address one without addressing the other?

Swapan Kumar Biswas, who has been in hiding since that day, later admitted that after learning what was about to happen, he felt like committing suicide to save himself from the impending humiliation. "But I couldn't do it thinking of my three children, my wife and my mother," he said. In hindsight, he would consider himself "lucky" to have come out of it alive. In India's Rajasthan, not long after, a tailor was beheaded purportedly for a social media post supporting Nupur Sharma. This debate that has caused so much outrage and counter-outrage simply refuses to be over, in yet another example of the deepening polarisations across the subcontinent.

But should we be happy that the worst was averted in our case, or sad that even such humiliation is somehow not tragic enough? Robbed of their dignity, can teachers do what they have been historically expected to do? While any teacher can be in trouble in a vicious, lawless climate, minority teachers have had a particularly rough go of it lately, especially when the allegation is "hurting religious sentiments". Before Swapan Kumar, we had Amodini Paul, Hriday Mondal, Pabitra Kumar Roy, Shyamal Kanti Bhakta, etc. Last week, Utpal Kumar Sarkar was beaten to death by a student apparently incensed by his disciplinary measures. After that, the University Teachers' Network demanded an end to attacks on teachers.

A fair demand, of course. But moments of grief should not distract us from the wider issues at play here.

Let's face it. Teachers are being attacked not because they are teachers, nor non-Muslim teachers the only ones subjected to the modern-day Inquisition, as evidenced, this Friday, by the brutalisation of Prof Ratan Siddique and his family. But there seems to be a narrow, ahistorical sense of victimhood, an illusion that things happen in a vacuum, isolated from other, larger developments. Journalists, political activists, rights defenders and social reformers have all felt singled out at different times. The truth is, in an environment where intolerance is encouraged from the highest seats of power, anyone using their conscience or not toeing the line is fair game.

If there is an innate vulnerability in all this, it is the minority status in a majoritarian tyranny. This is as true in India/Pakistan as in Bangladesh. Islamophobic provocations in one country can result in Hinduphobic provocations in another. There are historical precedents going back decades that show how such reactions have been reciprocated, often with devastating consequences. When majoritarian emotions run high, minorities make easy targets. So in India, they tell Muslims and immigrants to go to Pakistan/Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, they tell Biharis and Hindus to go to Pakistan/India. The cycle keeps repeating itself. It's like we've never really come out of our collective Partition trauma.

But it is possible to defend one's faith or guard against assaults on religious sentiments without condoning violence. It is possible to consider Islamophobia immoral without making it illegal. Unfortunately, despite having the garb of a secular polity, our laws, most notably the Digital Security Act, make "hurting religious sentiments" a punishable offence. Often, though, those are used to serve majoritarian interests and, as in case of people like the Narail student, as a tool to calm frayed nerves.

It's like correcting a wrong with another wrong, only it doesn't work. Forget the right to freedom of speech. By enacting such laws and still letting zealots have their satisfaction before the law is allowed to intervene, we're basically trying to force-stop all ideological debates. We're so invested in the short-term gain of such tactics that we fail to realise that matters of the heart cannot be resolved by force, legal or physical. Our ideological differences will perhaps never go away, but we can learn to sit together and find a way through compromise.

The Narail incident shows how this simple wisdom is getting harder to follow with the whole state apparently set on a collision course with reason, civility and justice. Increasingly, police are indistinguishable from the criminals they're supposed to deal with; politicians are openly stoking hatred and divisions to serve vested interests; democratic institutions are run on an exploit-first-serve-later basis; and the judiciary is either ineffective or irrelevant or actively enabling a culture of impunity. A suffocating environment prevails in nearly every sector because of the corrupting influence of politics.

There is no one villain, or one victim, in the Swapan Kumar saga. All of good had to fail for all of bad to be successful. We need to fix this state of affairs before we have a chance of fixing how teachers are being treated.

Badiuzzaman Bay is assistant editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments