In search of lost respect

In a popular TV ad, a jet set businessman yells at an airport steward, "Do you know who I am?" The steward takes a sip of her tea and announces, "Ladies and gentlemen, here's someone who doesn't know who he is. Can anyone help?" The hot-air balloon of authority with which the passenger wanted to garner respect gets deflated by the steward's sharp wit. The crowd laughs; the man soon loses his face and disappears. The message is simple: respect is not a one-way street. If one expects respect to pay dividends, then one must invest in a social relational calculus.

The man in suit demanded preferential treatment. In a bygone era, a branded suit, watch or a peg of whiskey would have conjured respect and made him "special." In a bygone era, professional markers like the chalk and duster of a teacher, the wig of a judge, the apron of a doctor or the pen of a journalist would have garnered respect. The respect dynamics is changing in tandem with the ever-evolving society.

Is it good or bad? Rather, the question is: What is good? Being respectful is good, while the absence of respect for others is bad. A man cannot simply approach someone in a threatening voice to demand service. There are norms and etiquettes. Respect is a means to an end. For instance, teachers earn their respect through years of dedication to their studies and students and after fulfilment of other social concerns related to their profession. Then again, a novice teacher earns respect as an end in itself by joining the legacy of moral underpinnings associated with his profession.

The recent spate of attacks on teachers by individual students or certain groups made many of us revisit the very notion of respect for teachers. True to its Latin root, respicere, the word "respect" literally wants us "to look back at." While reflecting on the attacks, most think that we have regressed from this idealist state where a teacher was once revered. A teacher beaten to death with a cricket stamp by an aggrieved student in front of his students and colleagues is the nadir of morality. A teacher being forced to wear a garland of shoes allegedly for discipling his students is a sign of decadence. A teacher assaulted before being thrown into jail for discussing evolution in class is a sign of regression.

Most opinion pieces and vlogs share a view that teaching is a "respectable" profession. As an educator, it pampers my ego to see many even quoting Kader Newaz's poem, in which the Emperor of Delhi Alamgir chided his son for not scrubbing the feet of his teacher with his own hand. Some even cited the anecdotal references to show the importance Bangabandhu and his daughter had given to their respective teachers. The sad reality is that, when it comes to career choices, teaching does not top the list. I think explaining the attack on teachers as a sign of moral degradation involves a false premise that paints a rosy picture of teaching and learning. The myth of teaching as a noble profession needs to be dispelled if we are to diagnose the social ills responsible for the attack on teachers.

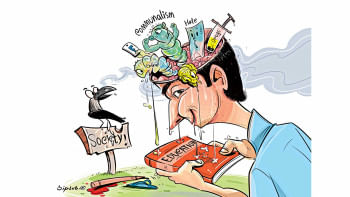

By a strange coincidence, the victims in most of these recent cases belong to the minority sect. This gives rise to further speculations and suspicions. Some focus on the religious identities of the victims to detect a systematic pattern to distrust the moralist position that pits the teachers against their students. The general sentiment of the commentators includes the waning respect towards teachers and elders in general, the lack of "proper" and ethical education in our young adults. The list skateboards to touch cultural anthropology on one rim and political economy on the other.

Since the perpetrators are all young adults, it will perhaps be useful to focus more on the intragroup dynamics. The tendency to explain the problem from our worldview in which we expect our current student pool to behave like "Emperor Alamgir's son" will not yield any result, especially if we keep on superimposing our values on theirs. We need to remember that we are dealing with the first generation of students who have not known a world without the internet. They know that Google knows a lot more than their human teachers. They do not need to rely on a teacher or ascribe her or him with a power position like their previous generation.

A recent survey by Stanford University discerns the major traits of the current generation. This is the generation that believes in instant gratification and expects praise for everything. They are not interested in following the footsteps of their predecessors as they believe that they alone understand the complexity of their own lives and situation. They are not interested in criticism or being disciplined for their wrongs. They believe that nobody is special. As a father of a millennial, I know how we do a disservice to the young ones by comparing the world in which we grew up to remind them of the way they should behave.

The attack on teachers is a criminal act, and it should be treated as such. But I do not see why we should make it profession-specific. I do insist on introducing mutual respect as an institutional norm not only in education, but also in other sectors. Respect needs to be cultured as a desired and valued principle. It needs to be promoted as something that entails a relational appreciation from those "others." Instead of pitting teachers against students, we need to work on intragroup dynamics, if we really want to see changes and earn mutual respect.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is pro-vice-chancellor at the University of Liberal Arts Banladesh (ULAB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments