Naked cities

During a run for essentials, I ran into a graffiti on a wall at a Philadelphia exit ramp: "Civilisation is pandemic." On any other day, I would not even think twice about such a street-smart philosophical pronouncement. Pretentious as it is, the graffiti does ring a truism about the double-edged nature of what we mean by civilisation. With civil now at a standstill—the Latin root for both civilisation and the city—the viral indictment is very much on the city.

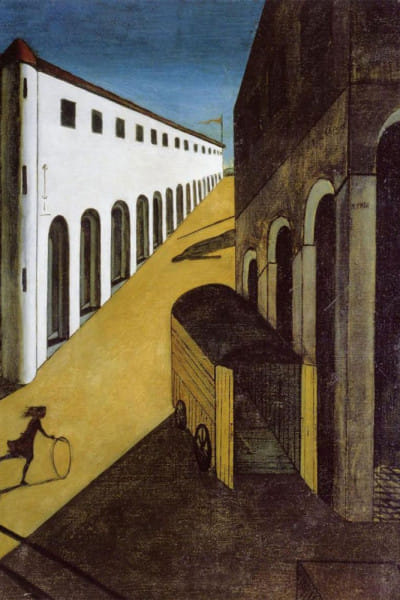

An uncanny silence has descended on our cities. Like a scene in a Giorgio De Chirico painting, public spaces in all cities are now deserted, long shadows crawl down a colonnade, stealthy figures in masks scurry down a street, and all basic signs of civic exchange have vanished. In Philadelphia where I am now, children have disappeared from parks and streets, and the streets seem to harbour something insidious. In Dhaka, Bangladesh, the other city that I belong to, the city that is forever bursting at the seams, an unsettling quiet hangs over many of the once thunderously raucous streets.

Such decapitated cities, devoid of people, with their streets and public life nulled, force us to face something very fundamental. If, as the Athenian general Nicias famously claimed, "we are the city", then what are cities if we have just vanished from sight? If, as Angela Merkel wonders, "our idea of normality, of public life, social togetherness—all of this is being put to the test as never before," will this unbearable emptiness redefine how we might come together again, and whether we may become a different sort of we?

For now, laid bare by the virus, naked down to our quivering souls, banned from our instinctual spaces, we are terrified, as if facing an ontological fundament. This is not the urban scene we imagined in the 21st century. This is also not the naked city that I, as a young boy in Dhaka, used to see in that eponymously titled American TV series from the 1960s that depicted the dark side of New York City.

Precautions against Covid-19 are extremely simple but excruciatingly unbearable—social distancing and staying at home. A touch—a fundamental way of being human—is all that it takes to be all right, but that is now denied. With the six feet distancing, quarantining and lockdowns at home, the coronavirus is dictating an anti-urban spatial arrangement.

But being in a city and retreating into it at the same time is a totally new phenomenon. Living in such a limbo is unbearable. Terrorised by our naked cities, we look for solace in other narratives.

A sudden view of starlight in an urban street, the improbable improvement of air quality, the arrival of flamingos in Mumbai and jellyfish in the lagoons of Venice. Each naked city has starkly revealed how a blooming urbanisation has also been a poison to the environment. In no moment in recent human history has the city seemed so villainous and vapid. Many yearn for a primordial purity in which the city, aka civilisation, has not trammelled the wilderness that, they argue, has now unleashed this interminable havoc.

The naked city has also revealed a horrific inequity that lies just below the surface of the urban spectacle, consumer hoopla and media distractions. No amount of diversion can now conceal the brutal fact of the number of deaths, especially in vulnerable communities. Aggravated by the velocity of the virus, harsh truths about social inequalities—from under-resourced hospitals to devastated doctors, protesting nurses, hungry citizens, suffering minorities and cordoned off wealth—are no longer invisible. How poignant to recall the epic line with which the show The Naked City ended: "There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them." What was said for New York City now resonates in every city of the world.

Although we don't know if the city will remain as it is or has been, but new imaginations are already in demand.

We have often reformed and rearranged our cities and societies following disasters. "Disaster demanded a new dawn," the English novelist Zadie Smith wrote in The New Yorker on April 10, 2020—"Only new thinking can lead to a new dawn." We can learn from previous post-disaster urban rebuilding, such as the Great Fire of London (1666), the Chicago Fire (1871), and the Great Kanto Earthquake of Tokyo (1923), but this new dawn that is to come will redefine how we are the city for generations.

Perhaps new academic themes will flourish, such as "epidemiological urbanism" that will take public health more seriously in the matters of urban planning, or a "viral urbanism" in which gaps, distance and isolation will be organised to dictate our civic life. There will be more commonsensical revisions in the practices of being in public. More contactless services and exchanges. Death of the handshake. Buttonless elevators and self-sanitising doors.

A call to interrogate the more insidious stuff needs to be turned up: Rapacious development and untrammelled expansion of the city should be paused, and devastation of the wilderness and wetlands should be reversed. Will this urban turn supersede or augment the conversation on the other defining crisis of our times: climate change?

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and urban designer, and directs the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments