Our local marine megafauna need urgent protection

It is rather thought-provoking to see how the growing interest in conserving terrestrial megafauna (for example, the Bengal Tiger) is starkly different from the interest in preserving marine megafauna (sharks, rays, turtles, whales). Animals living in water are generally considered as "fisheries-related" and inherently tied to food consumption and livelihoods, although ecologically, a tiger and a shark are equally important for ensuring the balance of the natural world. Our failure to properly appreciate marine animals as animals with the right to thrive in their own habitats is directly shaping our perceptions of them as generators of food and livelihoods. This leads to conservation actions that often fail to adequately prioritise marine animals.

For this World Oceans Day, I'd like to focus on a group of local marine residents from the Bay of Bengal who many do not know even exist in our coastal waters. These animals are essential catches for our coastal fishers because of their high value in international markets, but they also happen to be one of the most critically endangered groups of marine fishes in the world. As a result, they are stranded right in the middle of two important agendas—conserving marine species and ensuring the well-being of people dependent on them. Instead of treating them as separate, we must try to create a bridge between these agendas by envisioning them as a whole, where one cannot be achieved without the other.

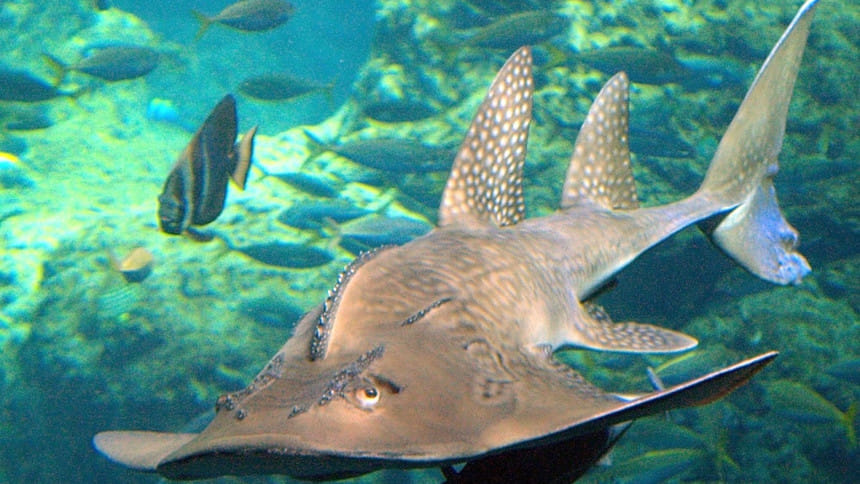

Many of these species have already lost up to 99 percent of their population in a large number of areas. Some were declared locally extinct from many tropical countries, such as the "rhino rays". The name is taken from the "Rhinopristiformes" family they belong to—in short, the rhinos of the sea, who are in no way less fascinating than the rhinos of the land. Typically characterised by the presence of a protruding and somewhat pointed snout, these species are one of the wonders within the larger story of marine animals and their evolution over thousands and thousands of years.

Landing and catch surveys in Bangladesh and neighbouring India and Myanmar indicate that the Bay of Bengal is a hotspot for several threatened and genetically distinct rhino rays. Therefore, it did not surprise us when we, through our marine conservation research at the University of Dhaka and the University of Oxford, found that rhino rays, including those globally threatened and nationally protected, are being caught and landed in unmonitored sites in coastal Bangladesh. They are an essential component of Bangladesh's marine biodiversity that support our artisanal fisheries (which depend on traditional/subsistence fishing). The diversity of rhino rays recorded in our studies is substantially higher than previously reported. They are caught with a variety of fishing gear, both as by-catch and targeted fishery.

At least 13 different rhino rays exist in Bangladeshi waters; it could be more. They belong to three broad groups—sawfish (with a saw-like rostrum which alone can be as big as five feet, whereas the whole animal can be 21 feet or more), guitarfish (the body looks like a guitar) and wedgefish (which have amazingly spotted bodies). Mainly thriving in Bangladesh's shallow and murky coastal waters, this group of animals is an integral part of our coastal and marine ecosystems. The Bay of Bengal provides one of the most suitable habitats for these species and potentially one of the last handful of habitats for globally threatened largetooth sawfish.

There are ample reasons for rhino rays to thrive in the Bay of Bengal. Between India and Indonesia, the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem (BOBLME) spans across six million square kilometres and includes vulnerable marine habitats forming four percent of the world's coral reefs and seamounts, as well as nearly a tenth of the world's mangroves, seagrass beds and extensive estuaries. Such ecosystem diversity suggests that BOBLME supports a rich habitat.

Our studies revealed that the warm tropical waters and shallow soft-bottom habitats along the coastline of southwest and south-central Bangladesh are very favourable to rhino rays. These regions also happen to be dominated by artisanal fisheries. The catch and trade of rhino rays in Bangladesh has been a common practice for decades. All of the nearshore shallow waters in Bangladesh are utilised by a fleet of vessels deploying an array of unselected gears. Artisanal fisheries, therefore, exert substantial pressure on rhino ray populations as they try to meet the increasing demands from the meat and fin industries in Asian markets and some other countries. What is even more interesting is that these pressures are exacerbated by the local belief (obviously untrue) that sawfish meat cures cancer.

Rhino rays have been a source of marine protein for coastal communities since the Bronze Age. The most valued rhino ray product is the fin, sold at very high prices internationally. In contrast to other countries involved in the fin trade (such as Indonesia, Malaysia and China, to name a few), almost every part of the rhino ray is sold in Bangladesh. Fresh meat and dried meat, fins, intestines, skin and bones are exported to China and Hong Kong and sold internally to local indigenous communities. Most of these products end up in south-eastern Bangladesh, from where traders export them to Myanmar. Customs checks are not conducted in this unique route, which is why monitoring is limited.

The scenario mentioned above is aggravated by continuous habitat loss and degradation in the nearshore soft-bottom habitats preferred by these species. Similar degradation has been reported in the mangrove forests of the Sundarbans due to shrimp aquaculture, increasing salinity, illegal fish poisoning, and intensive and unregulated fishing. Therefore, high fishing pressures and habitat degradation have emerged as an alarming combination barring the recovery of rhino rays. Unless we mitigate fishing pressures and trade, expecting a recovery of these species is impracticable. The steep decline of several rhino ray species in Bangladesh is evident. In our study sites, one fisher mentioned, "Even eight to nine years ago during the fishing season, there used to be regular landings of Fullaissha (local name of one species of wedgefish)—at least two to three every day. But I have not seen or caught one since 2009."

Rhino rays comprise a complex socioeconomic component in global and Bangladeshi fisheries. They are not just commercially significant; they also contribute to the protein intake of indigenous and other coastal communities. In light of the depletion of other marine species due to over-exploitation, rhino rays have become highly desirable alternatives. The harsh reality is that the demand for these proteins will only increase in the coming decades due to a continual increase in fisheries, especially in developing countries.

Millions of small-scale fishers in Bangladesh are highly dependent on marine resources for food security and micro-nutrients. By 2050, we expect our planet will need to provide sufficient and nutritious food for approximately 10 billion people, which suggests the need for continued expansion of global fisheries to maintain or improve human well-being. Yet, fish stocks and marine ecosystems already face depletion under current levels of fishing pressure. Bangladesh is no different, and the political interest is high to generate more revenue from the marine fisheries sector. While economic gains are necessary, they cannot be achieved in exchange for critical biodiversity loss. To promote sustainable rhino ray fishery practices that will help stabilise population declines, we need a holistic framework and a precautionary approach where conservation actions are taken before species reach a critical limit. Such a model would value evidence from science and promote local pioneers, collaboration and continual trials at the national and regional level, ensuring the well-being of both the fish and the people, which is precisely the theme for this year's Oceans Day: "Life and Livelihoods".

The fate of rhino rays in the Bay of Bengal depends on the individual and collective efforts of all stakeholders, and ultimately, the political will of all surrounding nations.

Alifa Haque is DPhil Researcher, Nature-based Solutions Initiative at the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, UK. To read more about rhino rays in Bangladesh, please visit https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105690

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments