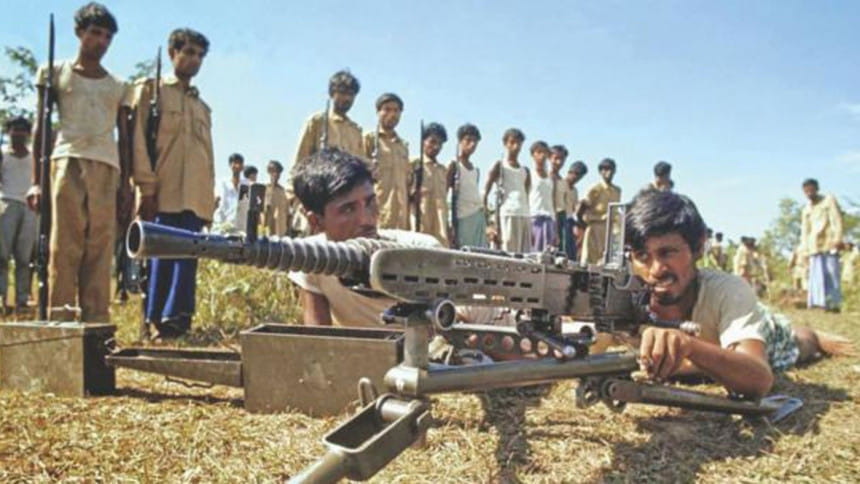

Our pride and glory: The Mukti Bahini in 1971

Bangladesh belongs to a select group of countries that fought their way to independence. We won our freedom by winning a fierce nine-month Liberation War against a very well trained, well-armed Pakistan Army. We remember with solemnity and gratitude the sacrifice of the millions of our people who achieved martyrdom, who were assaulted, brutalised and raped by the occupation army and had to flee their homes during the war. The occupying Pakistani Army brutalised us because they wanted us to surrender to them. Instead, the Pakistani Army's 93,000 soldiers laid down their arms on December 16, 1971, in one of the largest surrenders in history. On that day, Bangabandhu's Declaration of Independence of Bangladesh on March 26, 1971, became a reality.

In the 1971 Liberation War, we were victors, not only victims. Alongside paying homage to our people's immense sacrifice, we must also equally celebrate the pride and glory of our Mukti Bahini—the Bangladesh liberation army—in achieving victory and making independence a reality.

To say this is not to diminish the contribution of the Indian armed forces' leading role in achieving victory, for which we will always be indebted. It is, instead, to highlight the critical role that the Mukti Bahini played. The Mukti Bahini's victory with the aid of allied Indian forces in December 1971 was precisely analogous to the American Revolutionary Army's victory over the British Army in October 1783, aided by their allies, the French Army and Navy.

Two crucial tasks await. First, we must embed the stories of bravery of our Mukti Bahini in our national consciousness, telling our children how they fought relentlessly in the nine months before the Indian Army joined the battle to form the Allied Forces and jointly defeat the Pakistan army. Our school curricula, history books, movies and theatres need to tell stories of their tremendous acts of courage, heroism and dedication during the war. Second, we need to reach a more profound appreciation of the strategic role played by the Mukti Bahini in achieving victory. They were not merely auxiliaries as depicted in several Indian accounts, and as even some Bangladeshis believe. In nine months of war, the Mukti Bahini's attacks systematically destroyed the Pakistani Army's morale and supply routes and restricted their mobility. That, and only that, enabled the Allied Forces' lightning campaign, victory and liberation.

As a schoolboy in Chattogram in 1971, I saw and heard the Bangladesh Liberation War's first battles in all their intensity. On the evening of March 27, 1971, I saw, with awe, Bangladeshi troops—then East Pakistan Rifles—setting up positions and machine-gun nets on the Railway hill. I felt humbled knowing that they were getting ready to fight and die for Bangladesh. Later, reading the memoirs of a Pakistani Special Services Group Commander (Brig ZA Khan, The Way It Was), I realised that those soldiers and their comrades in Halisahar wiped out two companies of Pakistan's 2nd Commandos that had flown to reinforce Chattogram.

The Pakistan Army had to fight through Chattogram, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, to take over the city. In late March, we saw shells fired from PNS Jahangir on Bangladeshi soldiers resisting the Pakistan army's advance and Pakistani Air Force jets carrying out air raids to shut down Bangladesh's first independent radio station at Kalurghat. The Pakistani casualties in these March battles were so numerous that when they reached Dhaka, it caused widespread shock. After that point, to avoid demoralising their soldiers, the Pakistani military ordered that fallen soldiers' bodies not be returned to Dhaka.

Through the nine months, Mukti Bahini guerrillas kept continuous pressure at night through attacks on power lines, substations, buildings and other targets. On August 15, Chattogram's ground shook from the exploding limpet mines laid by Bangladeshi naval commandoes sinking Pakistani ships. In December, Chattogram's earth and the sky became fused by the cloud of dense smoke of the bombed oil refineries. The bombing of the Chattogram oil refineries was a heroic act by Flight Lieutenant Alam and Captain Akram of the emergent Bangladesh Air Force, who flew a single-engine Otter plane hugging the ground to avoid radar to make this daring attack.

What happened in Chattogram happened all over the country. After regrouping and training in India and the beginning of the monsoons, more than 70,000 Mukti Bahini soldiers, guerrillas, and sailors in river gunboats started continuous attacks on the Pakistani Army. These attacks took place not only in the border areas but also in the interior. Tiger Siddiqui's forces in Dhaka's North and the Toha faction of the East Pakistan Communists in the South fought unyieldingly from bases inside the country.

The Mukti Bahini's attacks over the nine months destroyed or damaged 231 bridges—including the vital rail bridge near Feni connecting Dhaka and Chattogram—and 122 railway lines, disrupting the Pakistan army's supply lines and mobility. Internal Pakistani Army briefings by June 1971 described the war outlook as a stalemate: they would hold the towns while the Mukti Bahini would control the countryside.

Even that assessment proved to be too optimistic as the Mukti Bahini started attacking in cities and towns. Bomb explosions inside and around prominent buildings such as the DIT, Hotel Intercontinental, government offices, and automatic gunfire became part of Dhaka and Chattogram evenings. Towns would plunge into darkness as guerrillas blew up 90 power substations and transmission towers. Army jeeps with mounted machine guns and Army jeep patrols became a familiar sight. As we know from the memorable account of Jahanara Imam in Ekatturer Dinguli, Pakistani soldiers were not safe inside the city as the Crack Platoon could brazenly attack them.

One of the most significant attacks took place in Dhaka on June 6, when Governor Tikka Khan was hosting a dinner for a visiting high-powered World Bank mission that had come to evaluate the situation. Just when the Governor and his officers were making the case that everyday life had resumed, the Mukti Bahini launched coordinated attacks around the Government House. As Hassan Zaheer, later Pakistan's Cabinet Secretary, writes in his account, "bomb explosions and machine-gun fire at regular intervals drowned out any attempt by Pakistani government officials to persuade the visiting mission that things were normal."

By November, the Pakistani Army had been fought to a standstill with enormous casualties: 237 officers and more than 3,695 soldiers had been killed or wounded by Mukti Bahini attacks. The demoralisation of the Pakistani Army was nearly complete, as evident from the following anguished passage from The Pakistan Army 1966-71, written by General Shaukat Riza: "[Pakistani] troops facing the enemy in one direction found themselves outflanked, their rear blocked. Troops moving from one position to another got disoriented and then encountered hostile fire when they expected friendly succour. By November 1971 most of our troops had... fought for nine months… in a totally hostile environment. For nine months they had moved on roads, by day and night, inadequately protected against mines and forever vulnerable to ambush… By November 1971, most of the troops had been living in waterlogged bunkers, their feet rotted by slime, the skins ravaged by vermin, their minds clogged by an incomprehensible conflict."

So, was the Mukti Bahini only another allied unit of the Indian Army, or did they play a critical role in the Pakistan Army's defeat? The evidence is compelling. The Mukti Bahini's contribution to victory was strategically decisive in at least five ways: first, their attacks broke the Pakistan Army's morale, as the previous paragraph makes abundantly clear. Second, the Mukti Bahini forced the Pakistanis to weaken their positions by spreading their forces thinly over the country. Third and fourth, they largely confined the Pakistanis to their bases, without reliable supply lines. Finally, they made the Pakistani army blind, devoid of that critical ingredient for battlefield success: information about what was happening around them. In his book Surrender at Dhaka, General Jacobs, then Indian Army's Chief of Staff in the East, recognises some of these factors even if in passing.

The plea here is that over the next few months, as we approach the 50th anniversary of our Independence and Victory Day, we launch a national campaign to tell stories about the glory of the Mukti Bahini and reach a national appreciation of the strategically decisive role of the Mukti Bahini. To make this effort creative and scholarly, let the Liberation War Museum take the lead in this campaign with the government's support. The Liberation War Museum's valiant efforts have collected many exhibits and artefacts, but surely the Museum appreciates that narratives by historians still await. Such a national campaign must quickly build up a library of oral histories of our freedom fighters and commanders. They should also draw on excellent books by General Shafiullah, Major Rafiq, Captain (Retired) A Qayyum Khan, and not least the 12 volume Liberation War Documents. These sources provide a wealth of tactical-level information. Finally, we have the brilliant book by Muyeedul Hassan, Muldhara Ekattor, that provides the most thoughtful and informed account of the Mujibnagar Government's historical leadership in 1971. We should draw on that book both as a source and as an example. Let what Muyeedul Hassan's book has done for the Mujibnagar government be done for the Mukti Bahini.

Dr Ahmad Ahsan is Director, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, and previously a World Bank economist and Dhaka University faculty. The views expressed here are personal. He can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments