Reimagining public university admissions in Bangladesh

The United Nations Committee for Development Policy (UNDP) recently recommended the graduation of Bangladesh from its Least Developed Country (LDC) status to that of a developing country by 2026. With the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as its prima facie directional narrative, and its transition towards the middle-income status looming, Bangladesh is tasked with using its public education system as a medium for endorsing a rigorous, state-level investment in human capital. A prioritisation of developing well-rounded university graduates for the workforce will undeniably ensure sustainable development across the board, rather than accomplishing nominal advances in GDP figures that benefit only a handful.

Policymakers often refer to a 98 percent primary-school enrolment rate and the integration of ICT in classrooms as being examples of how the state has unrelentingly prioritised the education of its citizens over the past decade. Nevertheless, there is a grimmer picture when it comes to the quality of education. Currently, Bangladesh ranks a mere 112th out of 138 countries according to the 2020 UNDP Global Knowledge Index (GKI). The GKI provides a holistic assessment of the impact of education by evaluating composite measures of pre-university education, technical and vocational education and training, higher education, research, development and innovation, information and communications technology, economy and the general enabling environment.

Figures such as a 36 percent secondary school dropout rate amidst high enrolment numbers (BANBEIS, 2020) and a 11.56 percent youth unemployment rate (World Bank, 2020) within the purviews of a neoliberal economic system are symptomatic of deep-seated philosophical concerns when it comes to analysing an empirical return on education, as clearly reflected by our performance in the 2020 GKI.

In simpler words, Bangladesh has a dire need to revamp, rethink and revaluate its education structures from top to bottom. And I think an intriguing area to focus on is defining a radical shift in the admissions processes for public universities and colleges.

The future of education lies in cross-disciplinary and experiential learning. The education system is, therefore, expected to create the basis for students transitioning into post-secondary studies to be adeptly prepared to engage in learning, research and solution-making from more than one academic lens. Unfortunately, our current system of standardised admissions processes discourages students to invest time and effort into developing skills beyond the classroom, making the childhood and schooling of students unnecessarily monotonous and intensely rigorous. We have all heard of instances of students enrolled in engineering or technology having proficient analytical and math skills, yet falling behind due to a lack of training, skills and knowledge when it comes to writing, public speaking or community engagement.

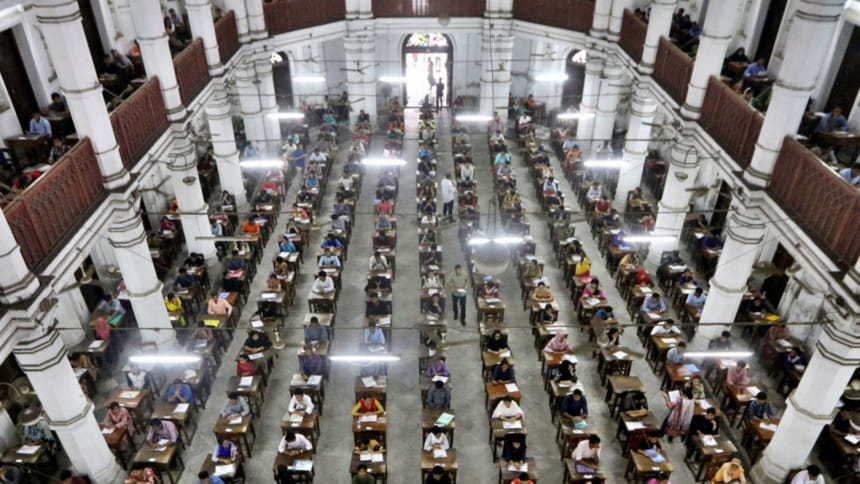

The blame cannot, and should not, be put on students. Standardised admissions systems that have pedantic academic testing schemes in place dissuade secondary school-going students from immersing themselves in co-curricular activities, such as volunteering, sports, theatre, etc. This in itself creates a student body which is solely focussed on in-class learning, usually with the motto of "one subject, one degree, one profession". The impacts of this are stifled creativity and students being deterred from undertaking activities that they may be passionate about.

Now, this is not to say that university admissions systems should not incorporate entry tests into the enrolment process. In fact, most developed countries such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand do integrate standardised testing as a partial requirement when recruiting students for undergraduate programmes. However, in my opinion, it is important to have a holistic measure of identifying the strongest candidates for various programmes. An all-inclusive, three-pronged system that includes an analysis of secondary school results, entry examination testing and a co-curricular submission component is perhaps a solid pilot scheme that can be tried across university programmes or departments with lower recruitment numbers. This can include departments such as political sciences, development studies or international relations.

With such an open-ended admissions process that involves departmental professors understanding the applicants more genuinely, it gives the students an opportunity to prepare for university life without being solely helmed in by the rigours of in-class learning. Having a well-rounded admissions process, which looks beyond academia, is therefore important for encouraging students to develop soft skills in the vicinities of leadership, communication, teamwork and adaptability—skills which, in the long run, are fundamental in shaping professional growth. Imagine university applicants having an opportunity to share their dreams and aspirations via an essay, and how much more university administrators can understand about their prospective students through such a component in the admissions process.

An open-ended admissions process can be subsidised through experiential learning initiatives across university programmes. The process of learning through internships and co-curricular opportunities (as part of a university programme) and experiential learning initiatives—promoted by the Education Ministry in partnership with corporate stakeholders, public institutions and non-governmental organisations—can create the basis for a more skilful graduate base in the long run. As mentioned above, these schemes can be piloted across departments that have a smaller student body compared to mainstream programmes such as engineering or medical sciences. At the very least, this can be a starting point for reimagining our education system.

Over the past two decades, Bangladesh has prioritised Goals 1, 2 and 9 (No Poverty, Zero Hunger and Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, respectively) of the SDGs. To make our economic progress sustainable and inclusive of the social development of a young population, it is crucial to put a national focus on revamping the education system.

Recently, Education Minister Dr Dipu Moni made the announcement that ethics classes will be introduced to students from the pre-primary to higher secondary levels in 2021. Such policy decisions are a reflection of what Goal 4 of the SDGs ("Quality Education") entails, and what communities are required to strive towards. Promoting lifelong learning opportunities through equitable and inclusive education systems is an area which both the minister of education and the prime minister have put thought to. In fact, PM Sheikh Hasina has been vocal in her concerns about issues of mental health and lack of physical activities being key barriers to the progress of the youth. Therefore, the expectation from the government and from education stakeholders is their interest and ability to transition from the archaic, colonial-era enrolment and classroom experiences towards a more holistic approach reflecting the needs of today's students.

University admissions systems need to be altered to incorporate non-academic skills of students. If not, then Bangladesh will keep falling behind in truly resonating with what quality education entails—be this in our performance in the Global Knowledge Index, or in our growing concerns regarding youth unemployment figures. In the long run, the education system, in conjunction with a cohort of rigid graduates that the system is creating, will be a tremendous barrier in our journey towards the middle-income status.

Mir Aftabuddin Ahmed is a Toronto-based banking professional.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments