Tackling the coronavirus crisis

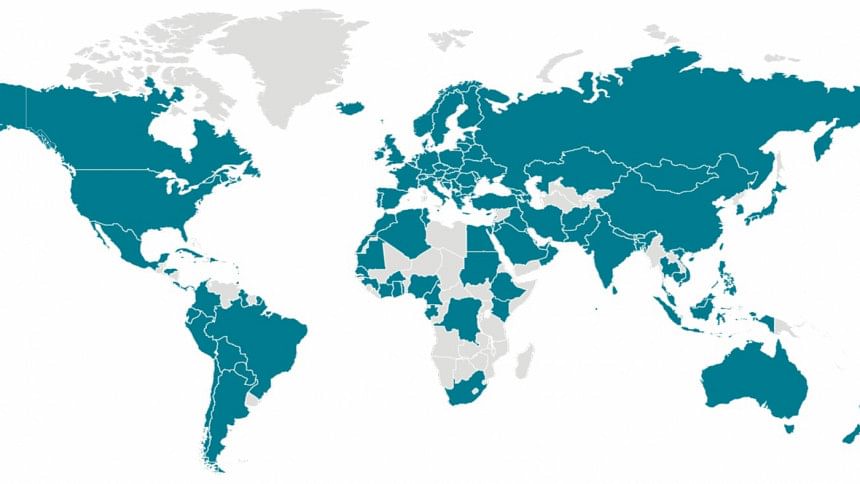

Covid-19 has now spread over 100 countries across all continents, except Antarctica, and has been classified as a global pandemic. This novel coronavirus has created the direst public-health crisis in generations, forcing lockdowns of countries, disrupting the global economy and restricting travel—all in just a few months since the disease began to spread outside of China. Bangladesh also reported its first few cases of coronavirus—all of which were imported from outside. As countries are struggling to prevent a similar outbreak, analysing China's response could show the world a path to follow.

China's response is particularly relevant at a time when Beijing is placing emphasis on the superiority of the "China model" that prioritises government control over individual freedoms. Such a model has become more evident in the era of President Xi Jinping. In contrast to paramount leader Deng Xiaoping's "hide and bide" doctrine—which essentially means waiting for the right time and not taking the leading role—Chairman Xi portrays China as a global power that is willing to lead this world with Chinese solutions, an alternative development model to western-style democracy. Therefore, the world is watching China's moves very closely as the situation evolves, including with regard to the latest episode of Covid-19.

This pandemic reveals the remarkable dynamics of China's governing system. China has been rebuked for its intolerance of dissidents, suppression of truth and controlling of information. Nevertheless, this pandemic has also revealed the strength of the Chinese system in mobilising resources and capabilities at an unprecedented level, in a way that is needed to rein in the virus.

Experts opined that to tackle a pandemic, the best solution is to share information with the public and take swift measures on the eve of the outbreak. In the Chinese style of governance, the decision is made via a top-down approach. At the earlier stage of the outbreak, Wuhan local government reported the presence of a SARS-like virus to the relevant department, but the higher authorities decided not to make the information public as an important annual political programme known as "two sessions" was due soon.

Despite the urgency to save thousands of lives, the local government was not allowed to disclose such sensitive information without the authorisation of the central government. Furthermore, China's giant, opaque bureaucracy slowed the back and forth of communication between provincial and central governments. Ultimately, the Chinese system failed to take any substantial measures after a month since the first case was reported, as early as mid-November.

Wuhan is a city of 11 million people—a larger population than that of Greece or Portugal, and centrally located in Hubei province, which is the gateway for China's rail, road, and waterways. The outbreak happened on the eve of the Chinese New Year—an event that leads to the world's largest annual human migration when Chinese people travel to visit their family and friends during this auspicious celebration. The news agencies reported that almost five million Wuhan residents traveled out of Wuhan before the lockdown, some even abroad. Consequently, long before even knowing of the existence of the virus, it is possible that many carriers spread it all over China and other parts of the world.

A doctor in Wuhan in his 30s shared the presence of an unknown disease with his colleagues via a WeChat group. China's digital surveillance system did not take long to detect the doctor's message and brought it to the notice of the authorities. Soon after, police arrested Dr Li Wenliang for an allegation of spreading rumours and forced him to sign a letter denouncing himself for doing so. He was released soon after, but Covid-19 had become a reality by then. The doctor himself was infected and did not survive the virus. His death, and the unfair treatment he received for a warning that could have potentially saved thousands of lives, led to a wave of protests in Chinese social media. Despite the tight digital surveillance, the public outcry over Dr Li's death went viral as millions of Chinese netizens from all walks of life posted this quote—"A healthy society should not have only one voice."

This crisis posed an unprecedented challenge to the Chinese authorities and forced the ruling Communist Party to take draconian measures. The gravity of the pandemic was later recognised by the high command of the party leadership, who sought to make all-out efforts to contain the spread, designating their efforts as a "people's war". Soon after, hundreds of millions of people were put under lockdown for weeks, hospitals were built within a few weeks, the military was deployed, party cadres were mobilised at the grassroot levels, several local officials were sacked for their negligence and medical supplies were sourced on an emergency basis.

The pandemic has now hit Europe, North America, Asia and beyond, but this public health crisis has also revealed the shortfall of western governance in replicating the China style measures, however drastic and draconian, that have been identified by the WHO as a model to tackle this pandemic. China, due to the centrally controlled one-party state, was able to implement such measures effectively. As a result, new cases are declining drastically in contrast to many parts of the world. However, one question remains—would the world even be facing this crisis if China had allowed the free flow of information and took action at the beginning?

Anu Anwar is an Affiliate Scholar at the East-West Center, US, and a Visiting Fellow at the University of Tokyo, Japan.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments