Who will speak for the George Floyds of Bangladesh?

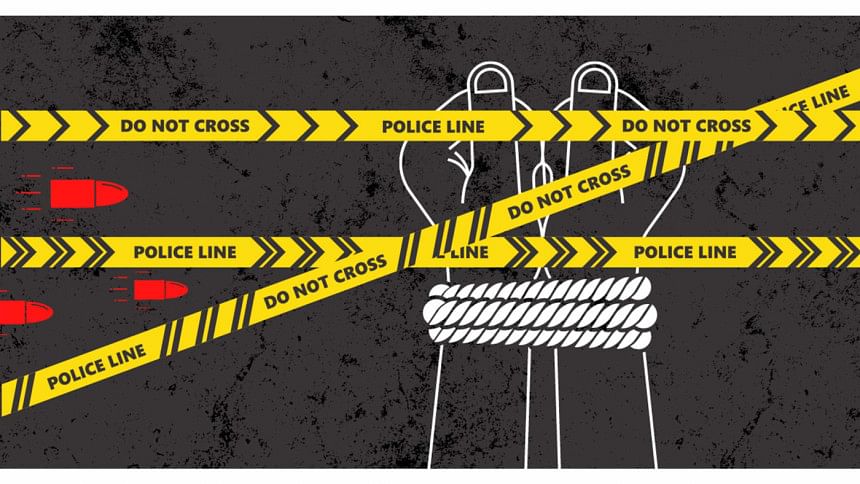

In the US, being Black or just a person of colour is enough to get one killed or arrested by a cop, merely for being at the wrong place at the wrong time—or even the right place at the right time. In Bangladesh, you just have to be poor or unconnected to anyone of influence to have to face the wrath of police. Thus, the horrible death of 26-year-old Rabiul in Lalmonirhat because he was "suspected" to be a gambler is hardly a shock, no matter how tragic the incident. It is tragic because there was no proof that he had gambled at the Baishakhi mela (fair), where someone who knew him said he had gone to buy toys for his daughter. And so what if he had been a so-called gambler—how does this justify policemen kicking him and beating him unconscious, and then taking him away only for him to be declared dead at a city hospital a couple of hours later? Apparently, law enforcement officials can not only detain anyone they wish, but they also have the right to use brutal force just because someone argued with them—or for no reason at all.

To add to the agony of a family who has lost a loved one and an earning member, there is little likelihood of getting any justice as they are scared to file a case against the police, who can file counter cases and make life intolerable for the family if they want to. After all, Rabiul's family members come from the voiceless, powerless class who are not entitled to any kind of state protection even if their lives are threatened. This means Rabiul can be declared a criminal, and there will be no one to clear his name—not even his fellow residents of Kazir Chawra village in Lalmonirhat, who blocked the highway to protest his killing, and certainly not his 20-year-old wife who has suddenly become a widow at such a young age.

Only a few days later in Cumilla, another young man, named Raju, accused in a murder case, was shot during the euphemistically termed "crossfire" with an official line that never gets too old for those who tell it: Rab raids an area based on a tip-off, the miscreants start shooting, Rab retaliates, the miscreants flee the scene, and one of them is found shot dead. Of course, it happens to be the one they were looking for. End of story. Ironically, in this case, the dead man is the suspect for the murder of a journalist; so now we have two dead men and seemingly no one to tell the courts what really happened.

These may be described as isolated incidents, but they are both part of a frightening culture of brutality and impunity that characterises our law enforcement's image today. The first incident, where policemen are directly involved, demonstrates the sheer helplessness of ordinary citizens at the hands of law enforcers. Human rights organisations have highlighted Section 54 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and the Special Powers Act, 1974 as laws that allow law enforcement officials to arrest anyone without a court order. Recognising the scope for abuse, the High Court has issued 15 directives that include specific instructions related to the arrest and treatment of a person in custody. This includes disclosing the law enforcement official's identity and if asked, showing his/her ID card to the person arrested, recording all the details of the arrest including the reasons why the arrest took place, allowing the arrested person to call his/her lawyer, ascertaining if the arrestee has any injury and taking him/her to the hospital or a government doctor for treatment, and getting a doctor's certificate regarding the nature of the injury. The law enforcement official is supposed to produce the arrestee at a court within 24 hours of arrest, and if this is not the case, he/she must explain to the magistrate the reasons for the delay. The magistrate has the power to decide if the reasons are valid enough for detention or whether the arrestee should be released.

In an article titled "Police power of arrest and remand" in The Daily Star, Barrister Md Abdul Alim explains that, in reality, without proper guidelines, magistrates often just follow a "parrot like" order on the forwarding letter of the police officer authorising detention in police custody or in jail." Thus, despite provisions in the law and in our constitution against torture and the use of excessive force, many law enforcement members have total disregard for either. They have been given inordinate power and have no accountability for its abuse. In the second incident, it is the same sense of invincibility that has led to yet another extrajudicial killing—the first after the US sanctions. In 2021, Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK) recorded 48 "crossfire" deaths and 21 deaths during "shootouts" before arrest, and six deaths due to torture after arrest.

People are afraid of law enforcers and see them as predators, not protectors. This is the damning truth that completely overshadows all the hard work that the police and Rab have done and continue to do in curbing crime and militancy in Bangladesh.

The US sanctions against Rab shows that these blatant violations of human rights do not go unnoticed by the international community, whatever the underlying agenda may be. It is the state's responsibility to protect its citizens, criminals and innocents alike, as guaranteed by the constitution. Major reforms in the police and other forces are crucial if we are to be recognised as a functioning democracy that upholds the values of the Liberation War and honours our constitutional rights.

But how do we reform forces that have been, by tradition, intensely politicised to serve the agendas of the government of the day? There lies the crux of the problem. The government must realise that, unless our law enforcement agencies are free from political influence, it will be impossible to hold them accountable for abuse of power. It will also be an uphill task to regain public trust in these forces, which can lead to increasing discontent, anarchy and space for criminality to get a free reign.

Aasha Mehreen Amin is joint editor at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments