All that glitters is not gold

On September 19, 2018, over the vehement objections of civil society and media representatives, the Parliament passed the Digital Security Act, 2018. The concern is that it is a draconian law which will impede freedom of expression, including individual and media freedom. More seriously, that it will be misused, as was the section 57 of the ICT Act. It may be used against the critics of the government, further shrinking our democratic space.

Despite such concerns, our ICT Minister termed the law as historic. We would like to remind the Minister of the old adage: all that glitters is not gold. The law may actually come to haunt those who have passed it in the future.

We can take the example of the Special Powers Act, 1974. Awami League (AL) was seriously criticised for the enactment of that law and, later, its leaders and activists became victims of the law's widespread misuse. A similar experience was with the Public Safety (Special Provisions) Act, 2000. This law was also enacted despite widespread objections; subsequently, AL activists paid a heavy price for it after relinquishing power.

Another example of a decision that looked good on the surface, but later haunted its framers, was the enactment of the 15th Amendment to our Constitution. It may be remembered that, in 2010, the government formed a 15-member committee with senior leaders of the Grand Alliance for recommending constitutional reforms. In addition to holding 27 meetings, the committee consulted three former chief justices, 11 senior lawyers and constitutional experts, 18 distinguished citizens, 18 editors and political party leaders. The experts and distinguished citizens, almost in one voice, recommended to involve the main opposition party and to keep the Caretaker Government (CTG) system. The committee also recommended accordingly. Unfortunately, the committee's recommendations later changed for unknown reasons, and the Constitution was unilaterally amended to exclude the CTG.

The Constitution represents the will of the people. The CTG was a settled issue, representing a national consensus. Despite this, the Constitution was amended using "majoritarianism", which, according to American founding father James Madison, represented a "tyranny of the majority". In a true democracy, especially a parliamentary democracy, the opposition is also a vital part of the government. However, "power politics"—capturing power or staying in power at any cost—has become the hallmark of our winner-takes-all system, making it almost impossible to unseat the government through free and fair elections.

The abrogation of the CTG amounted to "weaponisation" of the legal framework. Its objective was to create a "permanent settlement" on power by denying the opposition the opportunity to come to power through fair elections. We know from our history that no election held in Bangladesh under a political government was completely free and fair: The party in power won those elections by exerting influence on the bureaucracy and the law enforcement agencies. In recent years, the naked politicisation of government functionaries has made it almost impossible for the opposition to come to power by winning elections against the ruling party.

The purpose of the CTG was to prevent "the change of the election results by vote stealing, hooliganism, black money and the bureaucracy" (Sheikh Hasina, "Tothabadayak Sarkar Proshongay,' in Daridro Durikoron: Kicho Chitabhabna, Agami Prakashani, 1996). The Hon'be Prime Minister further said, "The irregularities in our elections must be redressed to make the system healthy. None of our country's problems would be solved unless the system of the changing of government is settled. The redressal of these irregularities would require arranging the next few elections under the Non-party Neutral Caretaker Government" (pp. 78-79).

After the unilateral removal of the CTG, electoral irregularities have become more widespread. Moreover, the constitution amendment, eliminated the need for the government to be transparent and accountable. Consequently, corruption and plundering have grown and the prospect of establishing good governance has disappeared. The distinction between the government and the ruling party has become blurred, with some party leaders and activists growing desperate and out-of-control. There are allegations that many have engaged in illegal activities under party protection, because they no longer must pay heed to voter sentiments.

Because of these excesses, the popularity of the current government and the ruling party has plummeted significantly. As a result, the government that came to power with huge popular support in 2008's landslide victory had to resort to a one-sided election to stay in power in 2014, which was facilitated by BNP's boycott. Even then, they had to resort to manipulations and partisan support of the Election Commission and law enforcement agencies.

The election of 153 uncontested MPs in 2014 had profound impact. The democratic system is a system of oversight, which requires one or more opposition political parties in and outside the Parliament to ensure transparency and accountability of the executive branch. The one-sided election of January 5, 2014 destroyed our Parliament's system of checks and balances with a make-believe opposition party, which was also a part of the executive branch. As a result, the balance that existed in our political arena was shattered, paving the way for a one-party government. Present concerns about the fairness of the coming elections are the result of such recklessness and naked display of power.

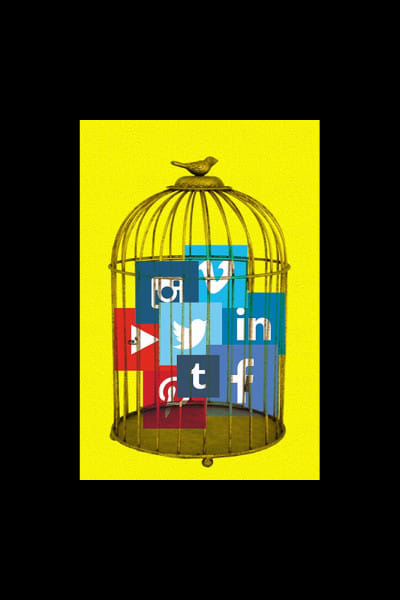

To conclude, it is clear that the government has delivered a sharp "weapon" to the law enforcement agencies in the form of the Digital Security Act. Unfortunately, our law enforcement agency has been the victim of politicisation, though it did not happen overnight or under one government. By delivering such a dangerous weapon to an agency that is both armed and partisan, the government may be able to gain some temporary benefits—but the lessons of history teach us that the fallout of the anger created from its misuse will have to be borne not only by the ruling party but by the entire nation. The gamble only pays off for the ruling party if they never fall out of power. And the law enforcement agencies are also at risk of worsening their already negative image in the estimation of the public.

We hope that the ruling party, which led our war of liberation, will think very seriously about the long-term implications of the Digital Security Act.

Dr Badiul Alam Majumdar is Secretary, SHUJAN: Citizens for Good Governance.

Comments