Column by Mahfuz Anam: Golden Jubilee Celebration - Media’s role and the diplomatic challenges in 1971

The mood of the moment is overwhelmingly celebratory. And why not? Not only are we observing 50 years of our independence, but we are doing so with a new sense of pride, accomplishment and, most importantly, confidence—confidence that we can face all the challenges that come our way.

Those of us who had the good fortune of being direct participants in our freedom struggle feel a special pleasure on this occasion. Being 20-something then and being 70-something now, many of us were not sure if we would survive the war in the first place—that we would live long enough to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of independence in person.

Recalling the days of our Liberation War is a matter of supreme pleasure—as it must be—but it is also one of great sadness. Millions of people—men, women and children—were killed, over 200,000 women assaulted, and millions more were made refugees in India, and a greater number internally displaced. The stunning success of our victory came at an immense human cost forced upon innocent Bengalis by the brutal Pakistan Army, a loss from which we are yet to fully recover, as is the case of the loss of our intellectuals.

All this happened due to the brutality of the Pakistan Army. How could an army attack its own people whom they were under oath to protect? Their brutality was not a one-off isolated incident that occurred in one village or two villages, in some remote part of the country. The genocide they indulged in went on throughout the nine months of our Liberation War. Such inhumanity could only be possible if it were rooted in racialism, triggered by a desire for ethnic cleansing.

For me and thousands like me, it all began in Dhaka University. Energised by the Six-Point and 11-Point movements, we were ready for the days of March 1971. Following the postponement of the National Assembly by then Pakistan President Gen Yahya Khan, students gathered at the famous "bottola" at the Arts Faculty in Dhaka University and witnessed the unfurling of what would become our national flag by the then Dhaka University Central Students' Union (Ducsu) Vice-President ASM Abdur Rab. The red-and-green flag with a yellow map of Bangladesh at the centre spread like wildfire as copies of it—both on paper and in fabric—were made spontaneously and distributed to whoever wanted to carry it. And, of course, everybody did.

With Bangabandhu's call for non-violent non-cooperation movement, the Pakistan government's control of what was then East Pakistan practically ceased. All government offices came to a standstill, all businesses were shut down—except for the essentials—and everything was focused on only one thing: how to get out of the clutches of the Pakistani rulers.

Dhaka was a city of processions and public gatherings from then on, with only one message: get ready for that long-delayed encounter with history. The gathering of March 7 and our leader's historic speech that all but declared our independence gave us a clear indication of the events to come.

The massacre that started on the night of March 25 marked the beginning of the end for Pakistan. The influx of refugees to India, the formation of the Mujibnagar government, the consolidation of the structure and command of the Bangladesh Army, the gradual maturing of the Mukti Bahini, and the rising effectiveness of their guerrilla activities were all leading towards our ultimate victory.

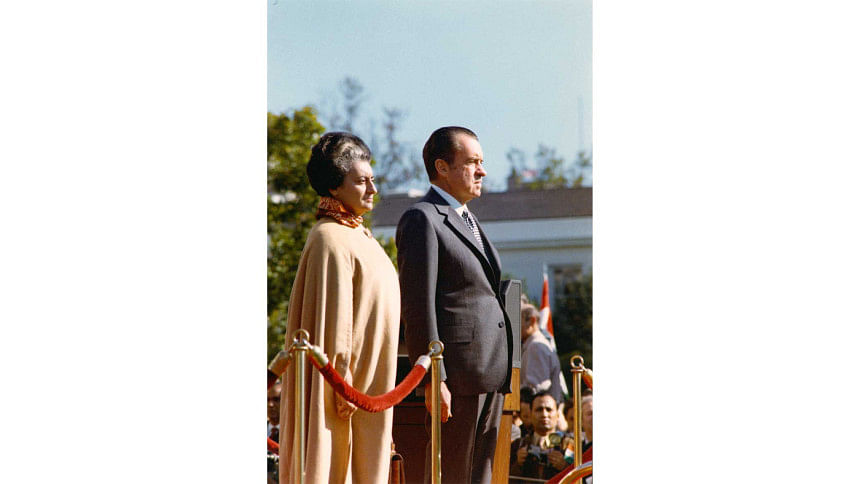

In our discussion on our Liberation War, two aspects have not been highlighted enough: first, the role of the international media, including that of India; and second, our success in the world of diplomacy, and the singular role played by the then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Bangladesh owes an enormous debt to the international media for making the world aware of the genocide started by Pakistan from the initial days of the war, and keeping that story alive throughout the nine months, and ultimately persuading the world public to see the reality as it was. It is often overlooked how the story of the massacre on the night of March 25, and the following days of brutal suppression of our people, were brought out through high-risk reporting in some of the most prestigious newspapers and broadcasting houses in the world. Throughout our struggle, the international media never lost sight of the events unfolding in East Pakistan, and contributed enormously in galvanising the world opinion in our favour.

The massive expose in the UK-based Sunday Times by Anthony Mascarenhas' (a member of a Pakistani team of journalists who were on an army-sponsored tour of the occupied East Pakistan, and who secretly escaped to London with his family before publishing his story) exclusive eye-witness account of the killing, torture, oppression of women, and displacement of our people made a significant impact on global conscience about what was going on. I personally remember BBC's role—especially of its Bangla section. The Indian media also played a vital part in not only covering the developments of our struggle, but also keeping the international media informed, as the latter regularly monitored the former to keep abreast of the situation. Akash Vani gave us invaluable support.

On the diplomatic front, it was an extremely difficult challenge. The bipolar world of the Cold War-era had set the international community apart with its ideological divisions and priorities. Pakistan was a close ally of the US and a long-term recipient of its military aid. On the other hand, India pursued a non-aligned policy, which the US always looked upon with unease and even suspicion.

China, probably because of the 1962 war and subsequent rivalry, veered towards Pakistan, and by 1971 was one of its staunch allies.

India had to navigate very carefully in this highly polarised international world and effectively counter the Pakistani propaganda that our Liberation War was nothing but an Indian ploy to bifurcate Pakistan. Thus, India needed to move slowly and focus global attention to the refugee crisis that was growing bigger by the day—seven million by August and 10 million by December—while providing the necessary logistics to the Mukti Bahini and the Bangladesh armed forces, not to mention housing our government in exile and providing security and other assistance to our leadership.

Much depended on how deeply China would be willing to go towards backing Pakistan, with clear early signs that the former took no notice of the events in our territory and unquestioningly toed the Pakistani line. Much also depended on the role of the Soviet Union—the other partner of the Cold War—which had not yet shown much interest in the Bangladesh affairs.

And here lies the success of Indian diplomacy and especially of its prime minister, Indira Gandhi, without whose clear, determined, and unflinching support for the Bangladesh cause, our victory might have faced harder obstacles. The Bangladesh government in exile, headed by Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmad, clearly understood that for India to act decisively at some point, China had to be countered by the USSR's active commitment in our struggle (see Muyeedul Hasan's article "1971: PN Haksar in bridging the security gap," published in the Victory Day supplement of The Daily Star on December 16, 2021). This necessitated both the internal redrawing of the political relationships and the reconfiguration of big power alliances.

The post-World War II pattern of global power received a massive jolt with the then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger's July visit to China, undertaken secretly from Peshawar, Pakistan, and subsequently declaring that US President Richard Nixon would visit China the following year. None of these developments escaped the notice of the Bangladesh government, nor that of India, greatly complicating the international power dynamics within which the Bangladesh government had to navigate. Earlier, Kissinger visited India and literally warned against any military action on Pakistan, saying that India could expect no assistance from the US in the eventuality that the conflict spilled over into something bigger. This warning, coupled with Kissinger using the soil of Pakistan to bring about the biggest shift in the US foreign policy in the post-war period, greatly worried the policymakers both in our government in exile and definitely in India.

The intimidation that the US stance really amounted to had the opposite effect on the Indian premier, who quickly signed, in August 1971, the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship with the USSR, significantly assuring mutual strategic cooperation in cases of conflict. This meant a significant shift in Indian policy of non-alignment since independence. Following the treaty, Indira Gandhi undertook a comprehensive tour—in September- November, 1971—of the Soviet Union, Belgium, Austria, the US, France and Germany to explain the Bangladesh situation and appeal for global cooperation in resolving it. When advised to go for negotiations with Pakistan, she said, "There is no India-Pakistan dispute involved. The negotiations must be held between the President of Pakistan and the duly elected leadership of the Awami League in Bangladesh." In a BBC interview, when asked about "restraint," she said, "When Hitler was on the rampage, why didn't you say, 'Let's keep quiet and let's have peace with Germany and let the Jews die?'" (See Praveen Davar's article "1971 War: How India's foreign policy was key to Dhaka Triumph" in the Deccan Chronicle, October 20, 2021).

The Indo-Soviet treaty stands out not only as a brilliant strategic move by India, but as one that is of tremendous significance to the birth of Bangladesh. It dissuaded China from getting militarily involved and acted as a caution for the US Seventh Fleet.

In a Cold War-ridden world, with the Vietnam War still raging, with Soviet-China rivalry at its height, with India's own military strength untested, and with the last moment opening up of the US-China rapprochement process, it was an unclear global power juxtaposition within which India had to undertake its most significant and dangerous strategic risk in going for an all-out support for the Bangladesh cause. It is my view that the role played by Indira Gandhi in support of our struggle for independence went far beyond the considerations of military balance between two rivals and gaining strategic and military superiority. The Indian leader's support for us was based on humanitarian consideration and genuine feeling that a historic wrong was being done to a people simply wanting democracy, for which it was being subjected to the atrocities of the most bestial kind.

As we commemorate 50 years of our freedom, we must realise the complicated world in which our leaders had to navigate, the risk—both domestic and international—that India took to help us, the contribution of our Mukti Bahini, and the supreme sacrifice made by our people, but for whose single-minded determination, untold bravery and suffering beyond all imagination, we could not have emerged victorious from so vicious a war in so short a time.

Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments