They gave their today, for our tomorrow

Jostling crowds, lots of offices, apartments, superstores, restaurants, boutiques, billboards, pharmacies, and very many vehicles typify the landscape of certain areas of contemporary Dhaka such as Mirpur Road, Green Road, Dhanmondi and Farmgate. The bustle and excitement of the big city serve to exhaust as well as attract people, and make them much too preoccupied with the present. I wonder if present-day inhabitants of Dhaka city sometimes tend to think about certain incidents that took place in these particular areas exactly 46 years ago. Or, if they are at all aware of the important and daring events of 1971?

Forty-six years ago, the Pakistani military occupied Dhaka through Operation Searchlight, the monstrous military attack mounted by the Pakistan army on March 25. Bengalis witnessed a reign of terror. The occupying troops were seen patrolling various parts of the city and their ominous presence instilled a great fear in the Bengali population. However, from June 1971, the Mukti Bahini's guerrilla units started entering Dhaka with the aim of unsettling the Pakistani junta by launching attacks on different establishments in the city using hit and run methods. These guerrilla attacks provided a much-needed boost for the morale of the Bengalis and made the Pakistani troops experience fright and anxiety in Dhaka for the first time.

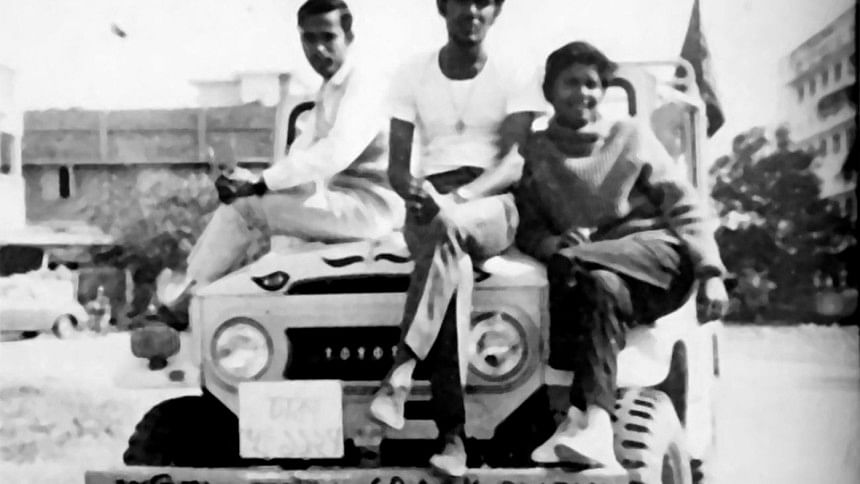

The Crack Platoon was one of the guerrilla units created in Sector 2 under the direct supervision of Major ATM Hyder. Hyder was a member of Special Services Group (SSG), the elite commando unit of the Pakistan army. In March 1971, he defected from his unit stationed in Comilla Cantonment and joined the Sector 2 forces of Mukti Bahini led by then Lieutenant-Colonel Khaled Mosharraf. Khaled felt the importance of forming a guerrilla unit composed mainly of young people who knew the city well. He assigned Major Hyder to train the Dhaka youths who congregated in Sector 2. Using his specialised knowledge of commando tactics, Major Hyder trained these young freedom fighters, desperate and determined to liberate their motherland, to become daring guerrillas. Habibul Alam, Bir Pratik; Kazi Kamaluddin, Bir Bikram; Abdul Halim Chowdhury (Jewel), Bir Bikram; Shahadat Chowdhury; Fateh Ali Chowdhury; Shafi Imam (Rumi) Bir Bikram; Bodiul Alam (Bodi), Bir Bikram; Mofazzal Hosen Chowdhury (Maya), Bir Bikram; Golam Dastagir Gazi, Bir Pratik; Ali Ahmed Ziauddin, Bir Pratik; Qamrul Huq (Shawpon), Bir Bikram; Azad; Masud Sadique (Chullu); AFM Harris; Pulu among many others were the members of the Crack Platoon.

The very first guerrilla operation was carried out in Dhaka on June 9, 1971. Alam, Zia, Maya and Shawpon hurled hand grenades into the porch of the Hotel Inter-Continental and made the visiting World Bank and UNHCR team members realise that the situation in Bangladesh was far from normal. On July 18, the guerrillas attacked five power sub-stations with a view to disrupting the electricity supply in the city. Of the five targets, Ullan and Gulbagh sub-stations were blown up by two guerrilla teams led by Golam Dastagir Gazi and Abu Sayeed Khan respectively. Pakistani soldiers had set up a checkpoint in a triangular road-island in Farmgate. It enabled them to keep a close eye on a number of roads. After reconnoitring the place a few times, the guerrillas attacked the checkpoint on August 8. Alam, Bodi, Maya, Shawpon and Pulu opened fire on Pakistani soldiers from the direction of Holy Cross College. Soldiers' tents were riddled with bullets, leaving several dead.

The guerrillas planned to stun the Pakistani authority by organising multiple attacks on August 25, because Operation Searchlight had started exactly five months before that date. On that day, a guerrilla team comprising Alam, Bodi, Kazi, Shawpon and Rumi fired from a moving car on the army sentries guarding a high-ranking army officer's house in Dhanmondi 18 (currently 9A). When their car arrived at Mirpur Road, they saw that the soldiers were checking all vehicles. The guerrillas could not turn the car back, so they decided to confront the Pakistani soldiers head on. Alam turned left to enter Dhanmondi 5 and Shawpon, Bodi and Kazi fired their automatic weapons continuously through the car windows. A military jeep soon started chasing them. But Rumi broke the rear windshield using his Sten gun and fired at the jeep. The bullets hit the driver and the jeep crashed into a lamp-post. Alam, turning on the left indicator, quickly took a right turn and returned to Mirpur Road from Dhanmondi 5. But the Pakistani soldiers turned left and rushed towards Green Road, thinking that the guerrillas had gone that way.

The young guerrillas conducted these extremely dangerous operations flawlessly. They remained unhurt during their attacks inside Dhaka. They successfully accomplished their mission of unnerving the Pakistani soldiers, giving the Bengalis a feeling of hope. But on August 29, on the basis of information provided by local collaborators, the Pakistani army managed to capture a few guerrillas. After torturing them inhumanly, they came to know about others, their hideouts, and hidden arms and ammunition. On the night of August 29, the Pakistani army raided several houses of freedom fighters and their well-wishers. Bodi, Jewel, Azad, Rumi, Chullu, eminent musician Altaf Mahmud and many of their relatives were taken prisoner. Kazi and Shawpon managed a narrow escape. Three and a half months later, the Pakistani army was defeated and Bangladesh became independent. But Rumi, Bodi, Jewel, Azad and Altaf Mahmud never returned to their near and dear ones.

Today, on another August 29, how many people remember that dark night when these patriotic and fearless young men had been captured? Do the members of our new generation have any interest in reading about the young Bengali guerrillas who were murdered by the Pakistani army in 1971? Are they familiar with the names of the other guerrillas who are still alive? Like many other freedom fighters, Rumi, Bodi, Jewel, Azad and Altaf Mahmud sacrificed their lives so that their countrymen could live in a liberated country. The documentary titled Muktir Gaan (1995) by Tareque and Catherine Masud ended by asking similar questions—Can we fulfil the expectations of the freedom fighters who sacrificed their lives for us? Can we uphold their noble aims?

I do not wish to sound cynical, but sadly, I am really not sure if the majority of the people in our present-day society tend to ponder such questions seriously.

Dr Naadir Junaid is Professor, Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, University of Dhaka.

Comments