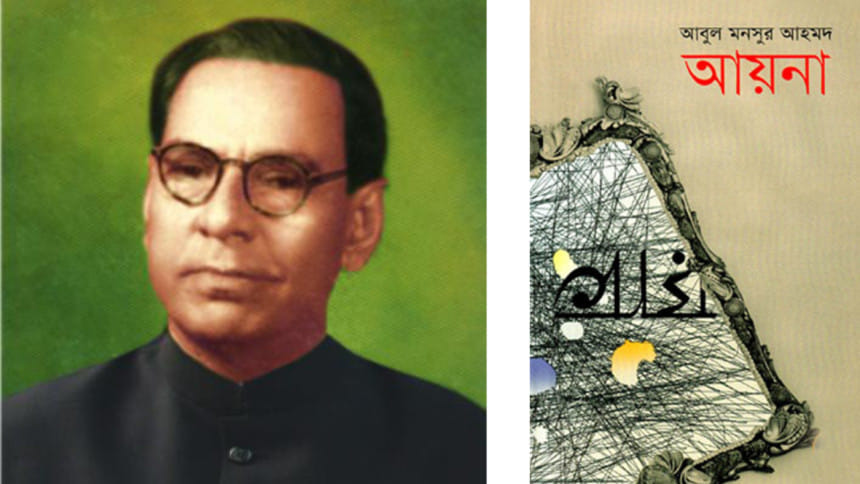

Abul Mansur and his all-seeing mirror

Today marks the 121st birth anniversary of writer-journalist-politician Abul Mansur Ahmad (1898-1979). The article is a translated excerpt from a review of his famous satirical work Aina, which launched his career as a writer, written in Bangla by National Professor Anisuzzaman.

"In ordinary mirrors, you see only the reflections of what is visible about men, but my friend, artist Abul Mansur has created a mirror that reflects the invisible, the veiled. In Abul Mansur's mirror, the real faces of masked men who roam amongst us, hiding their true agenda, get exposed in all of their monstrosity." Kazi Nazrul Islam wrote this in his preface to Abul Mansur Ahmad's "Aina" (Mirror), which pretty much sums up what the book is about.

Aina is Abul Mansur Ahmad's first book, a collection of seven stories published in 1935, although the stories were written much earlier, dating from 1926 when they started to appear mostly in Saogat. There were many other stories also but Abul Mansur Ahmad chose these seven for his first book. It is basically a satirical take on the follies and idiosyncrasies of our religious, political and social life. Buried between the lines, as one will discover while reading it, are subtle layers of pathos. As the writer puts it while dedicating the book to Abul Kalam Shamsuddin: "There is sadness hidden behind this smile, of which you are aware like no other."

In that sense, his stories are part-comedic, part-tragic. They prompt the reader to take a critical look at people's small-mindedness, deceit and ignorance—not just have a good laugh at the expense of his characters. Parshuram's influence in certain of his stories is unmistakable. But Parshuram's singular focus on humour is contrasted by Abul Mansur's design to get his social message across through the form—in that, it was a vehicle for him, a means to an end. To his credit, his design didn't limit his artistic expression.

In almost all his stories, Abul Mansur exposed the undersides of the contemporary Bengali Muslim society, his prose interspersed with Arabic and Persian words. Using such words is not uncommon in the history of Bangla literature. But I think, here again, Abul Mansur was sticking to his design when he used those words and phrases, not because these were particularly relevant for the text but because his characters would find them absorbing. For his characters and those they represented in real life, these words evoked sacrosanct reverence but little awareness of their actual meaning. The less they understood, the more reverent they would become. He considered this meaningless devotion a social disease.

Aina is set in contemporary Bengal of the 1920s and so today's readers may find it at times difficult to understand. They may fail to recognise some of the people or social practices that Abul Mansur's satire was directed at. Not many, for example, will be aware of the cow protection movement or the Aryan society of that time. Some of the subjects of his satire—the music-before-mosque riots (which arose following the deliberate conduct of a musical procession, usually as part of a Hindu festival, in front of a mosque, causing offense and often violence), the intense Hanafi-Wahhabi or Mazhabi-Ahle-Hadith debates, or other such references—have long become a thing of the past. But today's generation will still enjoy reading the stories as I surely did.

Abul Mansur's "mirror" basically stands on three legs: his lucid language and dramatic presentation, his skills in characterisation, and his exceptional observational prowess which he employed in his descriptions. His diction represents a distillation of diverse linguistic influences: he wrote primarily in the Sadhu Bhasa form but also, quite effortlessly, blended it with colloquial expressions and Arabic, Persian and even English words. This flexible approach to language helped him with creating the right environment as well as his characters in the stories.

The book, as we have said before, contains seven stories. The fraud pir in the story "Huzure Kebla" reminds us of Parshuram's Birinchi-Baba. Both men resort to tricks and seek their legitimacy by performing apparent "miracles" before their followers, but the pir in question does something more: he likes to spend time with the women. "Go-Dewta-Ka-Desh" is a story about a Hindu-Muslim conflict caused by an English-engineered row over cow, which ushers in an apocalypse. Then a flood of cow's milk inundates the whole country because there was no one left to drink it.

"Nayebe Nabi" tells the story of a fraud, rabble-rousing mawlana, while "Leader-e-Kawme" is a story about a man who, by taking advantage of the gullibility of the faithful, accumulates vast wealth and becomes the owner of a newspaper, later a great leader of the country, and earns further acclaim by spending some time in the prison. "Mujahedin" is about how god-men use religion to incite Hanafi-Wahhabi conflicts for their own parochial gains. "Bidrohi-Sangha", on the other hand, unmasks a group of iconoclasts who are, however, unwilling to do anything for their nation as they are secretly afraid of those in power. Lastly, in "Dharma-Rajya", we see a bloody conflict between Hindus and Muslims caused by a Hindu-led musical procession in front a Muslim mosque.

It's not possible to discuss Abul Mansur Ahmad, or even "Aina", within the space of a short article. What I did so far is scratched the surface of what constitutes the tip of his literary talent. His courage deserves a particular mention here. Through his satirical stories, he ridiculed people and social practices deemed sacred even to this day. And it was—this should be highlighted—tolerated by the society of his day. I doubt if any editor today will have the courage to publish such stories—and if the society will also tolerate it. Abul Mansur Ahmad waged a battle not against any particular person or religion or community, but against the stereotypes, prejudices, and superstitions of his society. This is what makes him and "Aina" so relevant for today's generation.

The article was translated by Badiuzzaman Bay.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments