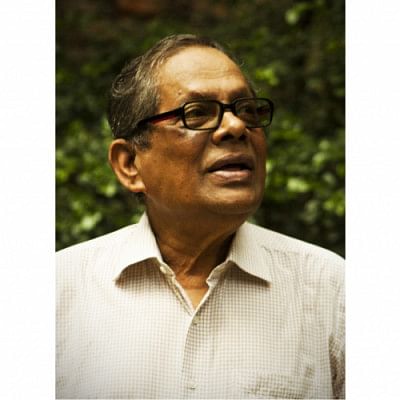

Adieu, Architect Bashirul Haq

A Bangladeshi pioneer departed this world on Saturday, April 4, 2020. Architect Bashirul Haq was a poet who crafted his poems with the language of brick, green, light, air, and tactility. Some of his brick buildings are like inhabitable poetry, where one experiences space as one would read, say, Jibanananda. Architect Louis Kahn once famously asked, "What do you want, brick? And brick says to you, I like an arch." If this was Kahn's celebration of the brick's quintessential material property (that brick can only be an arch but not a lintel), Bashirul Haq expanded that property into the realm of poetics, meditating with bricks and bringing them home, where they naturally belonged: the Bengal delta. In his architectural work, rural and urban were reimagined as an expression of organic cosmopolitanism.

Bashirul Haq's design epitomised an entwined brand of indigenous and modernist impulses in Bangladeshi architecture since the independence. For the new nation of Bangladesh, the decade of the 1970s was a complex tapestry of optimism and pessimism. The euphoria of liberation soon dissipated within the maze of political unrest, assassinations, and military dictatorships. Reminiscent of many other post-independence countries in social turmoil, a contested search for a national identity ensued. Furthermore, the Cold War-era politics—particularly, the shifting fault lines along the relationships among the United States, the Soviet Union, China, and India—complicated the internal affairs of Bangladesh.

Amidst the social tension of the 1970s, a new generation of ambitious architects burst forth onto the architectural scene of Bangladesh. The outcomes of a few national architectural competitions revealed new visions of modernity, building technology, and architectural space. Institutional and commercial buildings were no longer bland boxes, comprising corridors and rooms. In 1977, Bashirul Haq won the national design competition for the Bangladesh Chemical Industries Corporation (BCIC) headquarters in downtown Dhaka's Dilkusha Commercial Area. His entry showcased a new type of design energy that synthesised modernist aesthetics with a reasoned consideration for the local climate, a low budget, and a dense urban context.

Many of his subsequent brick buildings are considered architectural icons of the country, suggesting a sublime modern abstraction of Bengal's geographic ambiance. Haq's work is of utmost importance to explain how the notion of "critical regionalism" informed architectural modernism in Bangladesh since the early 1980s.

Born in 1942 in a village named Bhatshala, Brahmanbaria, a district in east-central Bangladesh and about 100 km from the capital Dhaka, Bashirul Haq developed a particular fondness for Bengal's rural landscape. He received his Bachelor's degree in architecture from the National College of Arts in Lahore, West Pakistan, in 1964. Lahore introduced him to the monumental architecture and gardens of the Mughals. Before he left for the United States in 1971 to pursue higher education in architecture, Haq worked in the office of Muzharul Islam, the first Bengali professional architect in East Pakistan. He was also affiliated with T. Abdul Hakim Thariani, designer of the country's national mosque, Baitul Mukarram, in downtown Dhaka.

Haq's journey to the United States played a formative role in his career development. He received his Master's degree in architecture from the University of New Mexico in 1975. The south-western American state of New Mexico sensitised him to the transformative influence of landscape on aesthetic development. In this state, the famed American artist Georgia O'Keeffe was deeply inspired by the phenomenology of layered limestone cliffs, rugged mountains, rock formations, and the meditative dance of light across them. Haq, too, experienced firsthand in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and beyond the introspective power of a place and how its paradigmatic adobe architecture could embody the spirit of a unique terrain.

Bashirul Haq was fortunate to find a mentor in Fazlur Rahman Khan (popularly known as F.R. Khan), a fellow countryman, partner of the famed Chicago-based architectural/engineering firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), and structural designer of Chicago's Sears Tower (now Willis Tower), the tallest building in the world from 1973 to 1997. The SOM stalwart took Haq under his wing and encouraged him to join his Chicago firm as an architect. However, as fate would have it, Bashirul Haq, already in his mid-30s, chose to return home, to Bangladesh. He was ready to embark on an architectural journey in the land he knew best.

There is a lot to learn from him. But how we learn from him is crucial. His work can be a great pivot to foster the production of "local" knowledge about the Bengal delta and its habitats. The lingering West-oriented tendencies of architectural curriculum in Bangladesh could be best mitigated when native knowledge is produced within a global-historical milieu of the built environment. There is a serious scarcity of architectural literature in Bangladesh. The predominantly design studio-oriented undergraduate architectural curriculum in the country neither encourages nor trains architects to think analytically about the design culture. Furthermore, a general lack of research initiatives in the academia only exacerbates the problem.

The lacuna of local knowledge production creates multifaceted problems. One of them is academia's continued reliance on imported West-centric books—often based on a false distinction between East and West—buttressing an uncritical belief in the perceived superiority of the West. Another related problem is that the absence of discursive conversation on local architects and their innovative work perpetuates a peculiar cultural self-pity that warrants western recognition as a validation of local designs.

Yet, to frame Bashirul Haq's work with the trite argument that he searched for local inspiration in his design and then sought to synthesise indigenous spatial qualities with modernity is to do disservice to his oeuvre that is complex, nuanced, and multi-layered. It would be unfair to see his architecture ricocheting between the false binary of local and modern. His work is much more. His sensitive and restrained use of brick as a building material tells richly complex architectural stories that elude simple classifications.

Bashirul Haq creates a cosmopolitan architecture, one in which the very premise of the local/modernity dichotomy is robustly resisted. Rather, he seeks to conflate an architectural archetype with a perceptive understanding of temporality and the spatial sensibilities of Bengal, but ultimately transcending the exigencies of the local. Experiencing his architecture, particularly his red-brick buildings, reminds one that searching for local inspiration does not have to be an inflexible moral burden, in the same way one feels that Alvar Aalto's Säynätsalo Town Hall (1949) seems to remain embedded in some kind of Finnish genius loci, while ultimately suspending the very need to be Finnish as an expression of aesthetic authenticity. In many ways, the exquisitely delicate use of brick in Haq's work, for example the architect's own residence on Indira Road in Dhaka, performs Bengali folk dance and western ballet at the same time.

To understand how Bashirul Haq resisted the temptation of compartmentalised historiographies of local and global (or East and West), one needs to appreciate the ways he values his cross-cultural architectural education. Like architect Muzharul Islam, Haq grasped the power of diverse geographies and how their cultures could blend together to produce all kinds of aesthetic chemical reactions.

Today Bangladesh thrives on design innovation and entrepreneurship, aesthetic experiments in materiality, and bottom-up community-driven buildings. The traveling exhibition Bengal Stream: The Vibrant Architecture Scene of Bangladesh (2017-2018), first held in Basel and then other European cities, my own cover article on Muzharul Islam in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (December 2017) and my travel companion DAC/Dhaka in 25 Buildings (2017), and three Aga Khan Awards for Architecture in the last few years showcase a growing global interest in the architectural developments of Bangladesh. Innovative research and analytical writing on the work of Bashirul Haq will broaden and validate this interest.

Adieu architect! You will be missed.

Adnan Zillur Morshed is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist. He teaches in Washington, DC, and serves as Executive Director of the Centre for Inclusive Architecture and Urbanism at BRAC University.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments