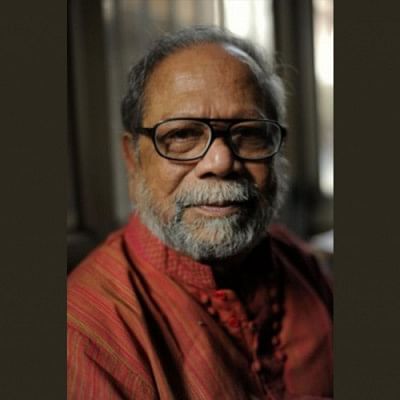

Remembering Murtaja Baseer: The master of ‘abstract realism’

At 75, Murtaja Baseer is as agile and hyperactive as a child, with a mind as sharp and clear. In his cosy apartment in Manipuripara, Baseer eagerly shows his oil paintings stacked against the walls and explains the various phases that he has gone through as an artist and the mentors who have helped him along the way.

Taking up art as a profession was somewhat decided by providence rather than a conscious personal choice. In 1947, Baseer was in class nine and was already influenced by Marxism. He became a member of the student wing of the communist party and drew pictures of Marx, Engels and Lenin for the Party. It was this association that paved his entry into the world of art and that heavily influenced the themes and subjects that he was to depict in his work throughout his life. The Party wanted to form cadres in all educational institutions and so Baseer was asked to join the Government Art Institute set up by Zainul Abedin.

At first, his father Dr Muhammad Shahidullah, a prominent scholar of literature and language and a doctorate holder from Paris's famous Sorbonne University, was not particularly excited about Baseer's academic choice. But his son's eagerness won him over and even induced him to give Baseer two rare volumes on the Louvre Museum that he had kept locked in his library for years. That was ample encouragement for the delighted 16 and a half-year-old, who spent hours studying the books and learning from them.

But Baseer's early days as an art student were far from smooth sailing. He was still very involved with left politics that ended him in jail for five months after he was caught putting up a Party poster on the wall. After being released, when Baseer came back to the Institute, he felt alienated and was apathetic enough to want to give up art altogether. "I told Zainul Abedin, my teacher, that I would give up", says Baseer, "but he said 'no' and called for Aminul Islam, one of his most brilliant and favourite students and a year senior to me." Aminul, with whom he shared the same political ideology, helped Baseer to get back on track and to improve his drawing and painting.

It was when he was in the second year that Baseer experienced an unpleasant experience that actually led him to start painting in oil. "I was doing a drawing in one of the classes when my teacher tapped me on the shoulder and asked me to get up and give my seat to another student Razzak, who always stood first in class. I knew I wasn't a very good student but I felt extremely insulted and ended up sitting in the corridor with tears streaming down my face." It was at that moment that the famous Safiuddin Ahmed, then a teacher at the Institute, stopped and asked him why he was crying. When he heard what had happened, Ahmed took him home, an unusual gesture for the reserved teacher from Kolkata. "I was a little surprised", says Baseer, "there were oil paintings done by him all over the place; Safiuddin was famous for his woodcuts at the time."

It was Safiuddin who encouraged Baseer to start doing oil paintings, often taking the young student along to various spots to paint. Baseer says that incident taught him a lot. Later as a Professor of Fine Arts at Chittagong University, Baseer says he always made sure that he would first go to the worst student in the class. "I think a teacher is successful," says Baseer, "if he or she can uplift the weakest students." When Baseer was asked at the interview board that decided on his professorship what he taught, he replied with "Nothing", further explaining—"I never impose my personality on my students, I only try to help them." Baseer acquired this way of thinking from his first mentor Zainul Abedin who, says Baseer, never encouraged his students to be like their teacher but urged them to try to develop on their own.

It was after 1954, in Kolkata where he went to take an art appreciation course at the Ashutosh Museum, that Baseer met Paritosh Sen who had just come back from Paris. Baseer was impressed with Sen's minimalism and his style of painting with palette knife. During his stay in Kolkata, he also learnt the technique of mixing water colours from famous painter Dilip Das Gupta.

Baseer says that it was in Florence, where he went for higher studies, that he was drawn to the pre-Renaissance painters such as Giotto, Cimabue, Duccio, Fra Angelico and others from the 13th and 14th centuries. "I liked the simplified drawing of these artists", says Baseer, "with their absence of perspective or shades of light." "Around '57, '58 I thought of something: that there is no such thing as so-called background and so I started superimposing in light and shade, making the main subject transparent." This translucent effect is found in many of his works such as Somnambular Ballad (1959), The Gypsy (1958) and Man with Accordian (1959), with traces of this even in later works in other media such as Girl with Flower.

The 60s proved to be another important decade for Baseer. In 1960, an exhibition of his paintings, drawings and lithographs was organised by the Pakistan Arts Council in Lahore. His second exhibition in Lahore displayed 28 of his works and were completely different from his "transparancism" phase. A brief period of despondency while in Lahore resulted in his depicting the darker side of life in Girl with Lizard and Dead Lizard, which he did in Dhaka.

In 1962, the artist got married and this is when he developed yet another style. "My life became very organised and structured", says Baseer, "and this was reflected in my work." The geometric shapes and female forms of his paintings at that time portrayed the emotional stability of the artist.

Baseer was always drawn to realism and the abstraction of modern art did not really appeal to him. "But I felt I was not in the mainstream with everyone moving towards the abstract; I started getting a complex", says Baseer. The artist remarks that he does not believe in pure abstract, which is often the result of alienation and angst of those societies in which life has become mechanical and vacant. The claustrophobia the country was facing in the late 60s however, influenced him to come up with his Wall series, which seemed to be the closest he had come to abstract art. But as far as Baseer was concerned, he was reproducing actual parts of walls that looked abstract because they were devoid of figures. This is when Baseer came up with a new term to describe his work: abstract realism. The walls denoted barriers between people, the emotional distancing in relationships.

In 1971, Baseer escaped to Paris with his family, fearing arrest for his involvement in the independence movement. It was during his stay in Paris that the Epitaph for the Martyrs series was done, inspired by the colours enmeshed in pebbles that he found on a Parisian street. The understated colours and forms of the pebbles represented a solemn epitaph for the martyrs who had died and were dying. In 1975, Baseer received the Shilpakala Academy Award, especially for his Epitaph series. He was awarded the Ekushey Padak in 1980.

In 1978, Baseer did a few paintings in his Jyoti series using religious motifs from prayer mats, scriptures and charms.

Baseer is very wary of repetition and says he stops as soon as he detects any sign of it in his work. Which is why he admires Picasso so much for his constant attempt to be innovative. He describes his "abstract realism" as the attempt to blend the vision of a Renaissance painter with the mind of an impressionist. The Wings series of the late 90s for example, is a completely new phase. The magnifying of a part of a butterfly wing in all its spectacular pattern and colour is a defiant protest and optimism against the degeneration of modern society. Again, in 1980, The Light series showed another form of work based on Quranic verses. "I was heavily criticised for this work", says Baseer, " I do not see any contradiction between religion and progress. Bangali Muslims are very progressive but that does not mean they are atheists." Baseer adds that the work of artists like Michelangelo and Rembrandt were heavily influenced by religious motifs so it is very natural for artists to use religion as a theme.

Baseer, the eternal optimist, is very hopeful about the future of Bangladeshi art. "Bangladeshi art is of international standard," remarks Baseer, " but there are constraints. The state must play a greater role and patronise art; there should be a Shiplakala Academy in every district. There are many abandoned houses all over the country. They can be turned into venues for exhibitions. All creative work including art, moreover, should be made tax-free."

Even after more than fifty years of creating a formidable repertoire of work, Baseer is far from being complacent. For Baseer, talent is an overstated word in art; it all boils down to sheer hard work, something this dynamic artist has never shied away from.

Aasha Mehreen Amin is Senior Deputy Editor, Editorial and Opinion, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments