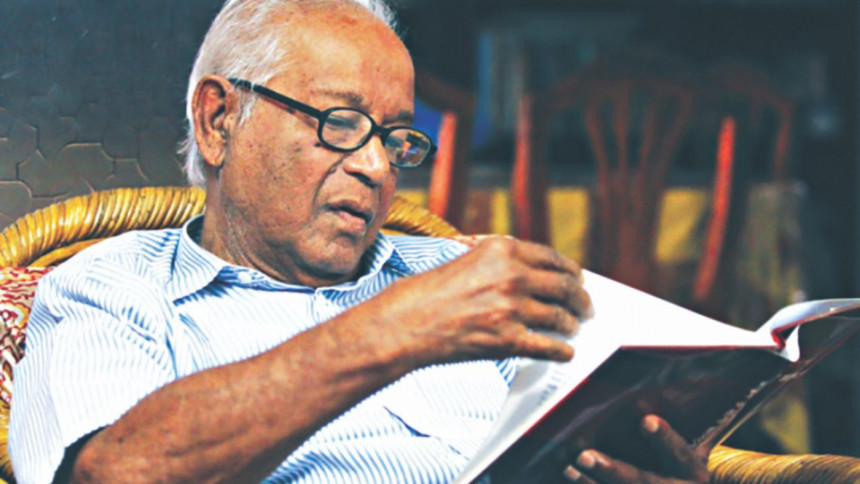

Dwijen Sharma: Sunshine on his shoulders

In the tranquil landscape and in the distant line of the horizon, he beheld something as beautiful as his own nature. In the wilderness, he found something more dear and innate than in cities or villages. The greatest delight the trees and woods showed him was the suggestion of an occult relation between him and nature. They nodded to him, and he to them. Even the waving of a tree in the wind was new to him. It took him by surprise—its effect was like that of a higher thought or a better emotion coming over him. But the power to produce this delight did not reside in nature, but in man, or in a harmony of both.

Professor Dwijen Sharma, botanist, naturalist and writer, found that delight in early childhood. His home was near Madhabkunda in Moulvibazar. His family had a garden in the mountains. He spent his early childhood amidst the flora and fauna, the birds and the animals of the mountains.

He once undertook a 15-day journey on foot from Mohanganj in Netrokona to Sunamganj in Sylhet to explore nature and collect botanical specimen on the way. Perhaps he was inspired by Henry David Thoreau's 1862 essay Walking, which extolled the virtues of immersing oneself in nature and lamented the encroachment of private ownership upon the wilderness. This inquisitiveness and love for nature took Dwijen Sharma, born on May 29, 1929 in Shimulia in Borolekha, Sylhet to many countries of the world.

His father, Vishak Chandrakanda Sharma, was a famous Kabiraj (a doctor specialised in Ayurvedic practices), and mother, Magnamayi Devi, a social worker. At home his father had a large library that helped shape his enlightened worldview. After getting his MSc in Botany from Dhaka University in 1958, he joined the B M College in Barisal and taught there till 1962. He took part in the education movement in 1962 and got arrested and stayed in a security prison for three months in Barisal. His goal was to study for a PhD in a foreign university. But he had to give up on that dream because he would not get a passport due to his "prison record." So he started doing research at Dhaka University. Then he got an offer to work as a translator for Progress Publishers of the then Soviet Union and left for Russia in 1974.

"When a traveller asked Wordsworth's servant to show him her master's study, she answered, "Here is his library, but his study is out of doors." Diwjen Sharma's study had been the roads, lakes, ponds, rivers, forests of Bangladesh and Europe.

A recipient of numerous awards including the Qudrat-i-Khuda gold medal, Bangla Academy Award, M Nurul Qader Children's Literature Award, Nature Preservation Award by Channel i, he has more than 30 books to his credit. His Shamoli Nishorgo (Green Nature), Shomajtontre Boshobash (Living in Socialism), Jiboner Shesh Nei (No End To Life), Phoolgulo Jeno Kotha (Each Flower Is A Word), Biggan Shikkha O Daiboddhotar Nirikh (Science Education and Our Responsibilities) and Nishorgo Nirman O Nandonik Bhabna (Building the Environment and Related Thoughts) are considered classics by critics and readers alike.

He served as vice-president of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh for three years. An encyclopaedia of the flora and fauna of Bangladesh in 56 volumes was published by Asiatic Society while he was the president of the publishing committee.

Dwijen Sharma aspired to think in a scientific spirit. It's a vague phrase, but one might start to explain it by emphasising values like curiosity, honesty, accuracy, precision and rigour. He didn't just pay lip-service to those qualities—that was easy—but actually exemplified them in practice—the hard part. The scientific spirit suggests that experiments ought to be done where experimentation is the likeliest way to answer a question correctly. Dr Jyotiprakash Dutta, eminent writer and professor at City University of New York, notes that adopting a rational and scientific attitude towards life as championed by Dwijen Sharma is extremely essential for the modern times but a majority of the population, particularly in our part of the world, have a hard time understanding it, mostly because of religious beliefs, superstition, lack of education.

At Notre Dame College, where he taught till 1974, he designed a landscape garden that still beautifies its campus. That's one thing about Dwijen Sharma—wherever he worked, he built gardens. Renowned folklorist Shamsuzzaman Khan said, "When I was the DG of the national museum, we made a botanical garden under his supervision in the back of the museum. Again when I joined Bangla Academy, we sought his guidance in planting trees on the premises of the academy."

He went to Russia with a dream. He dreamt that Dhaka would be a garden city—there would be parks, a riverfront on the banks of Buriganga, open fields where children would play—the whole city would be like Ramna Park. He wanted to learn from the Russian experience of socialism and then come back and work to rebuild the country.

While in Russia, he translated several books on political science, economics, sociology and science from English into Bangla. From Moscow he would visit Europe to see the birthplace of Darwin and the Kew Gardens, the holy grail of botanists all over the world. He would walk around in the Regents Park and St James Park and make plans about designing our botanical garden in the same fashion. He would carry a lunchbox and spend the whole day in bookstores. The libraries, museums, parks, herbariums of London had a great influence on him.

Dwijen Sharma's books are scientific and yet philosophical. In an article, Sharma writes about Chief Seattle, chief of the Suquamish and other American-Indian tribes around Washington's Puget Sound, who in 1851 delivered what is considered to be one of the most profound environmental statements ever made. His speech was in response to a proposed treaty under which the Indians were persuaded to sell two million acres of land for USD 150,000—"You must teach your children that the ground beneath their feet is the ashes of our grandfathers. So that they will respect the land, tell your children that the earth is rich with the lives of our kin. Teach your children that the earth is our mother. Whatever befalls the earth befalls the sons of earth."

He lamented that our cities in Bangladesh had become unliveable over the years. "This happened for three reasons," he explained. "During the colonial era, the British rulers imposed their model of development on us, distorting the natural socio-economic development of the subcontinent. Second, when Bangladesh got independent, the responsibility to build industries and develop the agriculture sector fell on the shoulders of the citizens of this new country. But we did not have any experience of urbanisation and industrialisation. So we built our cities without any proper planning. Third, the population exploded in a way that it put a heavy pressure on nature."

When he was not busy helping botanists with identifying a species or giving a lecture or an interview, he would take children to parks and introduce them to trees. Bipradash Barua, novelist, story writer and naturalist, said, "Whenever we face any questions related to botany, we call him. He is like an encyclopaedia. For example, if I see a new botanical species, I bring it to him. One look at it and he can identify it."

When a traveller asked Wordsworth's servant to show him her master's study, she answered, "Here is his library, but his study is out of doors." Diwjen Sharma's study had been the roads, lakes, ponds, rivers, forests of Bangladesh and Europe.

Amitava Kar is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments