Fly me to the Moon

"Hey, who will harvest potatoes for my kachchi biriyani in space now?" a colleague of mine commented alongside a Facebook meme on The Martian. The primary source of his joke was the removal of the civil servant with an agriculture background from the chairmanship of SPARRSO, Bangladesh's space research organisation. The secondary source of his joke lies in the sci-fi film featuring a stranded astronaut who survives on Mars by growing potatoes using his own faeces as manure. But it was no joke that on August 24, a team of Indian scientists successfully sent Chandrayaan-3 to put a lander called Vikram (courage) and a rover called Pragyaan (wisdom) on the dark side of the Moon.

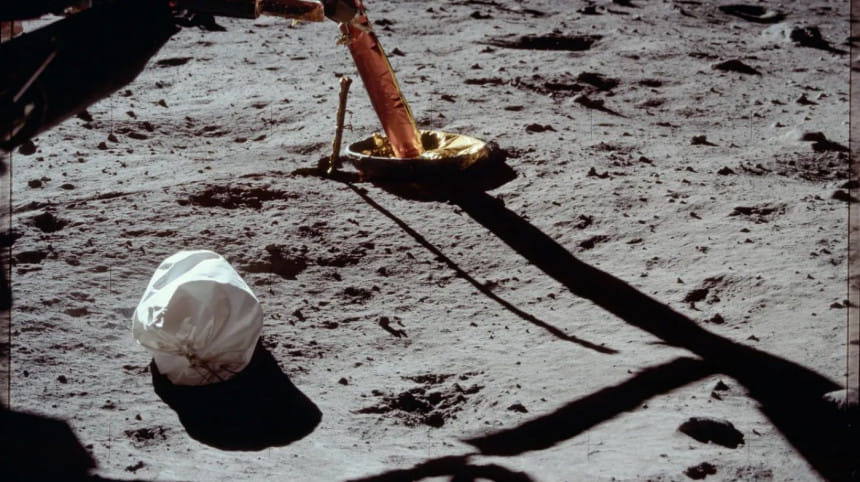

As a country where so many holidays are "subject to the sighting of the Moon," we have curiously followed our neighbour's brave lunar endeavour. The rover has already begun transmitting images from the surface of the Moon, providing valuable information for scientific research that will help better understand the Moon's geology, history and resources. One such image involves sacks of faeces left on the Moon's surface. It was not a pretty sight for our Earthly satellite, which is scandalised for its scars in local folklore. India deserves praise for dispelling many such superstitions and promoting Pragyaan with courage. However, a section of the Western media remains unimpressed by India's space exploration, which now involves a second expedition to the Sun. The media highlighted the lack of access to toilets in India, where hundreds of millions of people still defecate in the open, implying that the South Asian country has misplaced its priorities. The West has always regarded, in the words of the TV series Star Trek, space as the final frontier of their Enterprise. Between 1966 and 1976, the US and Russia conducted 19 of the total 21 lunar landings.

China accomplished its first lunar landing in 2013 after a 37-year hiatus, and outlined plans to dispatch humans to the Moon by the end of this decade. Now that India has joined this much-touted "Rising Asia" competition, the frontier tussle is gaining new currency. Nestled between these two rising superpowers, we ponder what the old lady on the Moon has been spinning for us! Given the tidal ebb and flow of a riverine country intricately linked to our climatic fate, one would presume that Bangladesh has an equal stake to the Moon. After all, we, too, grew up with the space ventures of Premendra Mitra's Ghonada or Satyajit Ray's Professor Shonku. After India's lunar landing, it was no surprise that everyone's attention turned to our space research.

A largely ignored government-sponsored research organisation specialising in remote sensing and computer modelling, Bangladesh Space Research and Remote Sensing Organisation (SPARRSO) suddenly came under unwanted attention. The portfolio of the bureaucrat who held the chairmanship of SPARRSO is no different from that of those who follow established rules, procedures and regulations to operate within the system. I scanned the list of previous SPARRSO chairpersons. Since its inception in 1980, there have been 26 people. The first 10 chairs all had PhDs, and a number of them are famed physicians. The founding chair, Dr Anwar Hossain, started his career at the Pakistan Atomic Energy Centre before moving to the Atomic Energy Centre in Dhaka. His successor, Faruq Aziz Khan, had a PhD from Canada and conducted research in nuclear physics in the USAEC laboratories. Then we had AA Ziauddin Ahmed, who worked in high energy physics at Imperial College London. After that, we had Dr AM Choudhury, who is famous for the development of the Rose Petal Theory for the forecast of cyclone tracks on the Bangladesh coastline. Sadly, only one of the past 15 chairpersons of SPARRSO held a PhD degree. And we had a rude awakening: we are running our space programme with bureaucrats just like any other government administrative branch.

If we truly want to harvest our dream of becoming smart global stakeholders, we must invest more in research and innovation. We must promote science and technology

What does it tell us about a country that aspires to become smart and ready for the IT-driven Fourth Industrial Revolution? Lack of clear vision hampers our space mission. The agency lacks a satellite launch facility, an orbit, and pertinent technology. It was even excluded from the launch of the Bangabandhu-1 Satellite – a US-based private company with French assistance oversaw the mission. One accessory that justifies the name SPARRSO is a ground station, which is also funded by foreign grants. There have been repeated media reports citing the fact that the agency lacks the personnel and funds necessary to operate a sophisticated space programme. In 2022, only 23 scientists out of 63 positions for officers and engineers were filled at SPARRSO.

If we truly want to harvest our dream of becoming smart global stakeholders, we must invest more in research and innovation. We must promote science and technology. We must abandon the mindset that joining the service sectors as civil, military or corporate administrators is the only career destination. Certain specialised areas should be left to the professionals. These field experts must be protected from bureaucrats who believe they can manage everything, including politicians. For our space dream to flourish, we must first create space for our specialists to prosper and develop.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments